What Breast Milk Can Reveal About Stress

Breast milk carries molecular signals that reflect a mother’s past childhood trauma and may affect an infant's temperament.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

The same milk that fills tiny bellies may also carry molecular clues about how babies will handle stress across the life course. Breast milk is a source of nutrition and contains molecules that can reflect a mother’s environment and stress exposure. For public health, these biological signals can help clinicians offer support earlier.

One place that stress can begin is long before pregnancy, in a caregiver’s own childhood. Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, include abuse, neglect, and serious household conflict. ACE exposure is linked to a higher risk of depression, PTSD, diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers across the life course. ACEs are also common. Estimates suggest nearly three out of four high school-aged children have at least one ACE. Children of parents and caregivers with higher ACE exposure are more likely to develop mental health problems, which turns childhood stress into a multigenerational public health issue.

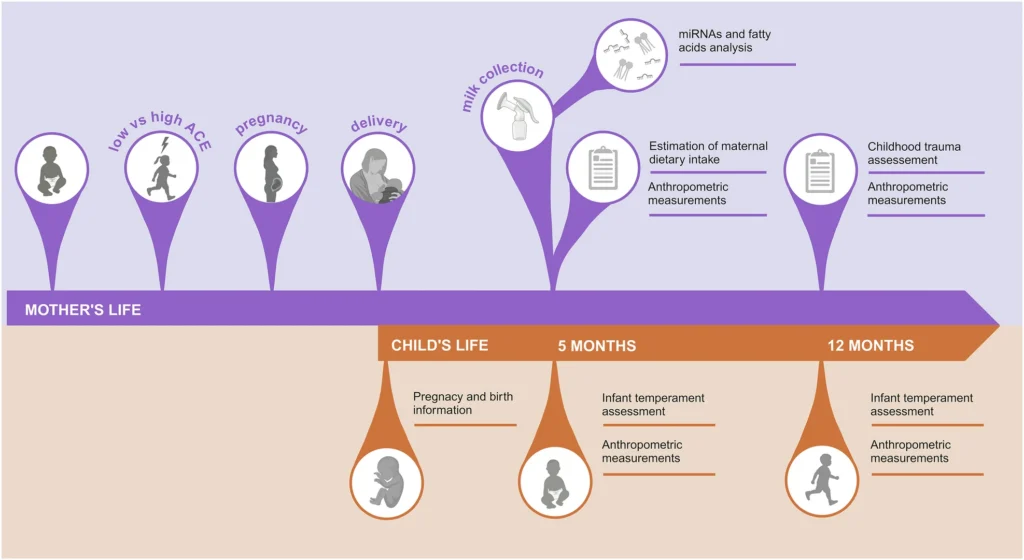

One question is how a caregiver’s earlier stress might show up in a baby’s first year. Weronika Tomaszewska and team followed 103 breastfeeding mother-infant pairs in Poland. Staff collected milk samples in the lab, recorded maternal diet and BMI, and measured infant growth. Mothers completed ACE questionnaires and reported postpartum depression symptoms. Parents later rated infant temperament at five and twelve months. In the lab, scientists measured tiny regulatory molecules that control how cells respond to stress and use fat, called microRNAs, and a panel of fatty acids in milk.

Mothers with higher ACE scores had higher levels of three microRNAs in their milk: miR-142-3p, miR-142-5p, and miR-223-3p. Their milk also had lower levels of middle-chain fatty acids, even after the researchers accounted for diet, body size, and infant sex. These measures lined up with temperament traits reported by parents in infancy. Higher miR-142-5p aligned with stronger high-intensity pleasure, meaning bigger, more energetic reactions from the child. It also aligned with more child distress at limitations, meaning more frustration when being told no or held back. Higher middle-chain fatty acids aligned with easier calming at five months and smaller emotional swings by twelve months.

From a public health angle, the value is not predicting outcomes for any one child. The value is using early signals to offer optional check-ins and support to families sooner. Pediatric and maternity clinicians can pair breastfeeding care with trauma-informed services that engage both parents when possible.

Childhood trauma can shape health across the life course, but it does not define a family’s future. If future studies confirm these patterns, the goal should stay the same: expand support and reduce barriers to care.