As Private Equity Consolidates Methadone Clinics, Patients See Few Gains

The private consolidation of methadone clinics has skyrocketed. But what happens when lifesaving treatment becomes dependent on profit?

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

In 2023, an average of 217 people in the United States died every day from an opioid overdose. Methadone, one of the three FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder, can reduce the risk of overdose death by nearly 60%—or 130 fewer deaths every day. It also reduces cravings and helps people slowly decrease their dependence on opioids while living healthier, safer, and more functional lives. But only 22% of people with opioid use disorder receive methadone, according to a 2021 study.

Experts agree that increasing access to methadone is a vital part of addressing the opioid crisis, but putting this recommendation into practice remains a challenge. In the U.S., methadone is strictly regulated, and only licensed opioid treatment programs (not hospitals, pharmacies, or doctors’ offices) can dispense it. Additionally, methadone must be taken every day, and many clinics have limited hours and do not allow patients to take medication home. This essentially forces people to structure their lives around their daily dose.

The exclusive control that opioid treatment programs hold over methadone distribution has attracted private equity firms, which see these clinics as a business opportunity. Private equity firms are investment management companies that raise money from investors and use it to buy private companies. These firms have the funds to improve operations, boost profits, and then sell the business within a few years. Often, one firm will buy many businesses in the same industry, consolidating its control over a specific sector, such as health care.

Over the past decade, private equity has rapidly increased its presence in health care, acquiring hospitals, physician practices, nursing homes, and fertility clinics. And while private equity ownership can give hospital systems the funds to invest in new technologies or the power to negotiate with insurance companies, it has also been linked with predatory financial strategies, worse patient outcomes, and higher costs. The recent demise of Steward Health Care was due, in part, to mismanagement and neglect under private equity ownership.

As private equity turns its eye to opioid treatment programs, advocates believe this kind of investment could expand access to methadone, filling the gaps left by inadequate funding from federal and state grants and lawsuit settlements. Opponents caution that if a few firms control a large share of clinics, it may limit the expansion of methadone treatment, leaving patients with fewer options.

In a new study, Yashawini Singh and colleagues investigated how private equity acquisition affects methadone supply in opioid treatment programs. The researchers combined data on opioid treatment program acquisitions from PitchBook with data on methadone shipments to clinics and county-level opioid overdose mortality rates. They then compared methadone supply in counties where private equity firms acquired methadone clinics with similar counties that did not experience any private equity acquisition.

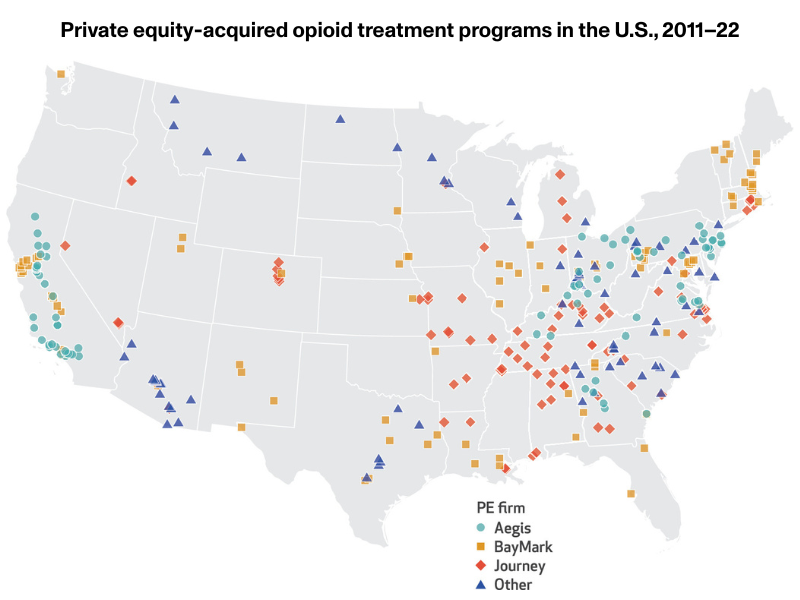

The proportion of opioid treatment programs that private equity invested in has grown dramatically, from just 0.26% in 2011 to 18.9% in 2022. During this timeframe, private equity firms acquired 357 clinics across 43 states, more than 75% of which were acquired by just three firms, shown on the map below. Often, one firm purchased multiple clinics in the same county.

The study’s findings highlight what happens when lifesaving treatment becomes dependent on profit-driven investment.

After acquisition, methadone shipments to individual clinics increased by 13% relative to similar clinics not acquired by private equity. But when researchers accounted for preexisting growth trends, that increase was no longer significant, meaning it could not be attributed to the acquisitions themselves. At the county level, overall methadone supply and opioid overdose mortality showed no meaningful change. The findings suggest that while private equity firms are consolidating control of opioid treatment programs, they are not expanding access to methadone in a way that helps address the opioid crisis.

Barriers to receiving treatment for opioid use disorder are already incredibly high. But when one private equity firm controls many of the methadone clinics in a given county, it has the power to cut corners and prioritize profitability over access to care, making those barriers even higher. They can also lobby against efforts to lower barriers.

In 2023, Senator Edward Markey of Massachusetts introduced a bipartisan bill that would allow pharmacies and physicians to dispense methadone. Such a law, if passed, would bring the U.S. in line with many other countries where doctors can prescribe methadone to patients, including Germany, Switzerland, and Australia. Physicians, patients, public health officials, and the American Medical Association agree that expanding methadone access in this way would be a safe and beneficial change.

But private equity firms have lobbied against these efforts to preserve their monopoly, arguing that licensed opioid treatment programs are necessary because they provide valuable counseling to patients (Investigations have shown that many clinics do not provide the counseling they claim to). The law did not pass and is considered dead.

The study’s findings highlight what happens when lifesaving treatment becomes dependent on profit-driven investment. The authors urge policymakers looking to expand access to methadone must be wary of allowing private equity to shape the system. Ensuring that treatment is driven by public health needs rather than financial returns is essential to reducing overdose deaths in the years ahead.