The ADA, 27 Years On

William “Nick” Crow discusses THE RIDE, the challenges and gaps in accessibility presented by old architecture, and how the ADA has made countless tiny reconfigurations to our landscape.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

As a kindergartner, William “Nick” Crow transitioned from what he calls “spec ed” to “mainstream” classes. Some of his schoolmates must have wondered why he needed to use a walker.

Just some months earlier, several activists left their own walkers and other disability devices at the bottom of the Capitol Building. During what came to be known as the “Capitol Crawl,” they advanced the steps using their arms and chanted “ADA now!”

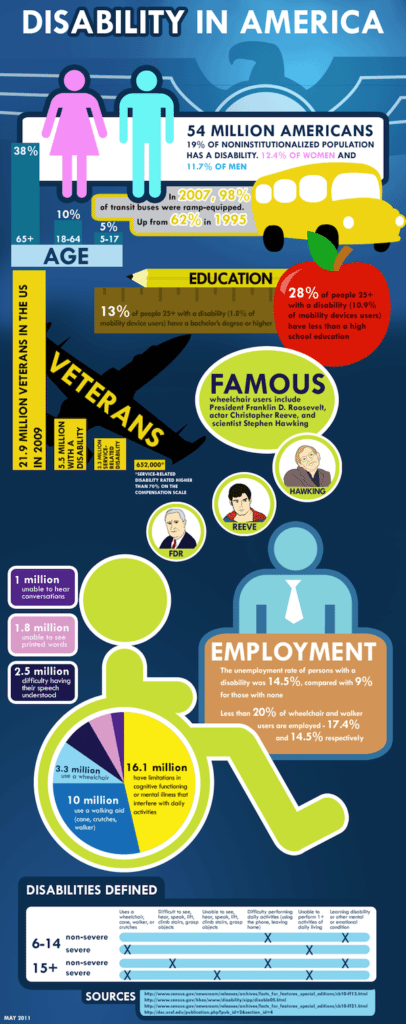

This was 1990, the year the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed. Parents had for decades sought an integrated curriculum and accommodations for their children’s impairments. The ADA furthered Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which banned discrimination on the basis of disability by recipients of federal funds. People with health conditions that interfere with at least one activity of daily living were recognized as a minority group.

Nick laughs when asked whether he considered himself disabled. “You try not to think about it. But it comes to the forefront more often that not.”

He numbers among the 2.4 out of 1000 who by age six are diagnosed with cerebral palsy. He has encountered many misconceptions about his non-progressive neurological condition. While he has used a motorized wheelchair since high school and has difficulties with fine motor skills, he points out that actor RJ Mitte actually played up his milder cerebral palsy symptoms as Walter White Jr. on Breaking Bad.

Nick “think[s] disability can stem from living in a big city, honestly. In the suburbs, people were always in a culture of tolerance and going with the flow.”

“Boston’s an older city. Unfortunately the builders didn’t have 300 years of foresight,” he says.

Some major provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act set requirements for public and commercial entities. Several major crosswalks in downtown Boston are fairly generous with walk time and are more likely to have auditory cues indicating that it’s safe to cross. Curb cuts are the actual name of the small ramps set into sidewalks at regular intervals. Doors have literally been opening – with the assistance of button-activated motors – for the disabled.

The ADA has made countless tiny reconfigurations to our landscape. However, when Nick moved to Boston he was most surprised how much of a challenge old architecture can pose.

“Boston’s an older city. Unfortunately the builders didn’t have 300 years of foresight,” he says.

He finds old architecture, grandfathered into non-ADA compliance, “frustrating but understandable. And I just can’t get in.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act nears its 27th birthday. Even so, Nick has found again and again that accessibility is not the default for many establishments. He suspects that ignorance and cost-cutting play equal roles. Changing that takes a complaint, with agencies including Housing and Urban Development, or sometimes the city itself.

After moving into his new apartment downtown, for instance, Nick realized that his double unit was not required to be handicap-accessible. “It’s taken cooperation from the building and adjusting in my own way,” he says, “I find new and interesting ways to advocate for myself.”

Nick works for the MBTA, determining eligibility for its paratransit service THE RIDE. An average day on the job might include him interviewing a few arthritic grandmothers, a music professor with retinitis pigmentosa, and a woman accompanying her non-verbal autistic son.

Nick educates his clientele and coworkers. But it’s gone both ways.

“Before this job, I will admit ignorance and arrogance,” he says of learning how physical, visual, cognitive, and psychiatric conditions prevent individuals from taking a public bus or train. “The RIDE has broadened the horizon of disability for me.”

Nick schedules RIDE trips for himself when unplowed ice or snow could pose a barrier for his powerchair. A single RIDE trip is priced between $3.15 and $5.25 for him, though the true $60 cost -that covers the trained drivers’ salary, vehicle upkeep, and gas- is subsidized by taxpayer dollars. The RIDE is one of the single biggest expenditures for the nation’s oldest existing transit system.

Nick regularly uses his disability pass for the MBTA, which saves money for himself and the system alike. His commute is made possible by the elevators at the stations, along with the bridge plate that allows his chair to cross from platform and the kneeling feature of all buses: all reasonable accommodations, along with the existence of the RIDE, that the MBTA must make to ensure accessibility for disabled riders.

“I prefer taking the T for independence. I’m more a part of society.” Nick says. “Boston has opened my eyes, and I’ve had to go outside my comfort zone.”

Feature Image: Nick Crow boarding a RIDE van. Photo: Kendra Sims.