The Downstream Harms of Upstream Oil and Gas Development

Maternal exposure to benzene, a carcinogen present in crude oil and gas, increases the risk of developing childhood leukemia.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

Though cancer mortality has declined in the United States over the past two decades, the incidence of several types continues to rise among younger groups. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is one such condition. As the most common pediatric cancer, it accounts for 25.4% of all childhood cancer cases.

This upward trend may stem partly from increased exposure to cancer-causing agents and partly because clinicians have gotten better at diagnosing the disease. Benzene, a potent carcinogen found in crude oil and gasoline, is a known risk factor for leukemia. Growing research shows that maternal exposure to benzene significantly increases the likelihood of developing childhood leukemia.

Environmental benzene primarily comes from upstream oil and gas development, which is the extraction of oil and natural gas from the ground through high-pressure “fracking” and drilling. These operations are highly destructive, releasing fumes, chemical contaminants, and benzene into our air and soil. Communities located within 3 miles of oil and gas sites experience higher rates of hospitalizations and emergency room visits compared to those living farther away from the pollution.

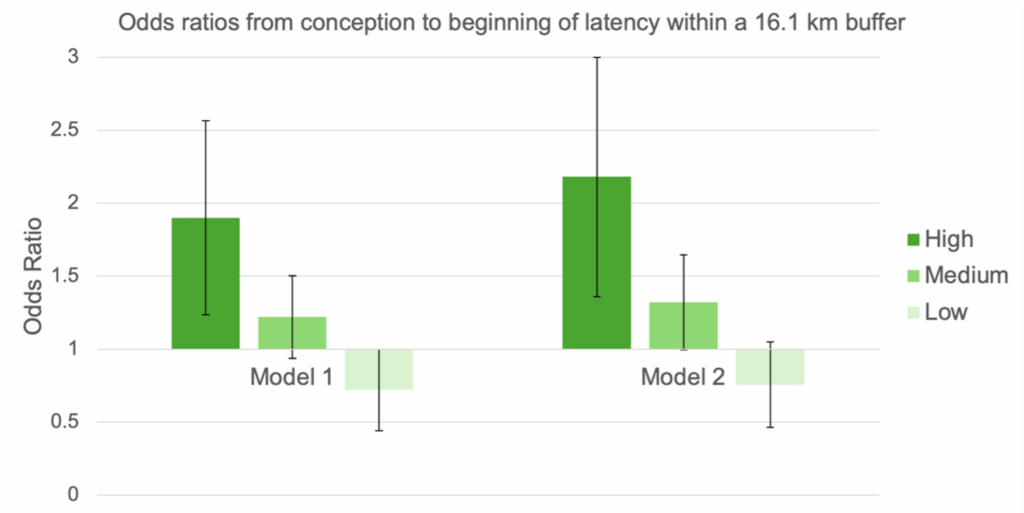

In a recent study, researchers investigated the link between childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and oil and gas extraction sites in Colorado. Using 1992-2019 birth and cancer data, they matched 451 children with leukemia between ages 2 and 9 with 2,907 cancer-free children. Each child’s exposure to pollutants from the drilling and extraction was classified as high, medium, or low based on their proximity to wells and drilling activity levels.

As shown in the figure above, children with medium and high exposure to oil and gas production faced a significantly greater risk of leukemia than those with low exposure. The analysis first accounted for differences in maternal age and child sex (Model 1). After considering these factors, leukemia risk increased 22% among children with medium exposure and 90% for those with high exposure. When the researchers considered other environmental factors—including other sources of air pollution and ultraviolet radiation exposure (Model 2)—the risk rose to 32% and 118%, respectively.

Children with leukemia were 2.5 times more likely to live within 13 kilometers of an oil or gas well than their cancer-free peers. Those who lived 5 kilometers away had a two-fold higher likelihood of being diagnosed with leukemia. This elevated risk persisted across all maternal exposure windows, including conception, birth, and all three trimesters.

The findings indicate that the current minimum distance requirements between oil and gas operations and nearby residents are ineffective against downstream environmental hazards. Colorado’s minimum distance is 2,000 feet, compared to California’s 3,200 feet. But pollutants can travel well beyond these limits. Expanding the distance requirements on a national scale is necessary to ensure adequate protection, and continued research is essential to uncover how this industry contributes to rising childhood leukemia rates.