Pain Drain

Thoughts on improving the health of populations

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Pain Drain

We live in a country that is in pain. Approximately 20% of Americans suffer from chronic pain. Through lost work and often ineffective treatment, chronic pain costs us $600 billion annually, more than cancer and heart disease combined. The emotional and social toll is uncountable.

Pain is lodged at the crossroads of the two epidemics that have distinguished this decade: opioid addiction and suicide. Pain and its mitigation were the rationale for the profligate (and deceptive) marketing of opioids when prescription pill sales quadrupled between 1999 and 2014. That widespread misuse and addiction followed was, perhaps, not surprising. Physical pain is sometimes at the root of psychic pain; sometimes isolation and despair produce another form of suffering, leading to suicide. Our two epidemics meet at a crisis of pain.

What we know now is that pain starts as a symptom—associated, for example, with arthritis or neuropathy—and for one in five Americans this symptom becomes “chronic,” that is, it lasts for weeks or months or even years. At some point during this period, the symptom becomes its own disease. Chronic pain has its own reliable neurobiology (which we are just beginning to understand), its own brain activation signature, although it cannot be localized in any specific “pain area” like other sensory perceptions such as smell or sight. Still, pain changes the brain’s structure, its neuronal configurations.

Pain’s significance and interference in a person’s life is highly individualized. The experience of chronic pain can be altered by mood, sleep quality, distraction, suggestion, or even anticipation of new pain. Which implies that pain may be exacerbated by social conditions—by violence, by anxiety. Living in poverty increases the odds of living with chronic pain.

Yet pain is argued over. Pain is important in our legal system and is the subject of disputes over payment for disability claims and personal injury suits. The lack of an objective measure of pain means that some who might deserve compensation miss out because they cannot “prove” pain, although we are getting closer to having brain scans presented as legal evidence. Pain is always a subjective experience, but there is a race to make it objective as well; prototype blood tests are also nearing clinical use.

Pain is a threat; it makes us feel helpless. It makes us ruminate and catastrophize. Decreasing avoidable suffering is central to our sense of being healthy. To become or remain pain-free is a nearly universally shared life goal. Assessing and treating pain, chronic pain, coping with its presence and limiting its ruinous effects without misusing opioids or taking one’s own life remains central to the mission of public health and the measure of our empathy.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

DEPRESSION STRIKES AGAIN

As we age, we develop chronic medical diagnoses that affect our quality of life. These investigators quantified the life quality burden of 15 common chronic conditions such as stroke, cancer, diabetes, and arthritis, alone and in combination, among persons 65 years of age and older. Ninety percent of this cohort had at least one chronic medical problem. Along with congestive heart failure, depression produced the greatest decrement in health. Programs designed to improve health at the individual and societal levels must address depression, a modifiable but undertreated condition.

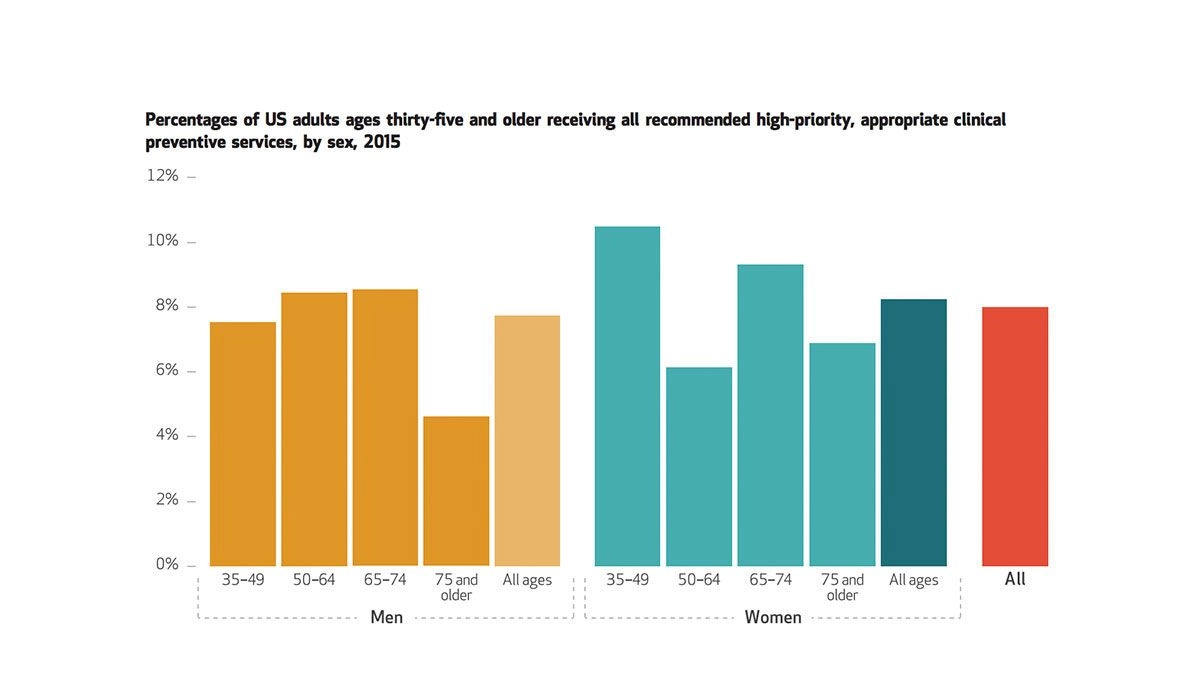

PREVENTIVE CARE DEFICIT

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, seven out of 10 Americans die from chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Costs associated with using preventive services may deter people from getting screened for these conditions. Globally, other industrialized countries have fewer financial barriers to prenatal, pediatric, and other types of primary care.

Routine primary health care is critical to preventing or identifying illness in early stages when it can be treated. It has also been a core objective of population health since the 1978 Alma Ata Health for All Declaration. But research on the use of such care in the United States has focused on specific services like colorectal cancer screening and flu vaccination. Borsky et al. developed a new, more comprehensive method to measure how many adults use the high priority preventive services recommended for them. Their survey asks participants about 15 types of evidence-based, clinically relevant preventive care, and accounted for inappropriate use and overuse.

The figure shows that, as of 2015, only 8% of all adults age 35 and older received all recommended high-priority clinical preventive services. This measure reflects the survey’s assessment of multiple types of preventive care. Taking a deeper look, Borsky and colleagues found 22.4% of surveyed adults received at least 76% of the recommended care. Compared to women, men were more likely to receive up to 25% of suggested preventive care services. Only 4.7% of all participants did not receive any recommended services. Blood pressure screenings were most commonly received, and shingles vaccinations least.

The researchers argue that the comprehensive nature of their survey instrument will be useful for health systems to assess the preventive services they offer and their receipt. The authors also emphasize that their questionnaire can be used at both the national and practice-specific level to help identify the impact of changes to local and national policy on preventive service use.—Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Graph: Health Affairs Vol. 37, NO. 6: Hospitals, Primary Care & More Datawatch, “Few Americans Receive All High-Priority, Appropriate Clinical Preventive Services” by Amanda Borsky, Chunliu Zhan, Therese Miller, Quyen Ngo-Metzger, Arlene S. Bierman, and David Meyers.