Blood Sugar Blackouts in the Backcountry

Diabetic children living in rural areas have more difficulty accessing continuous glucose monitors, a convenient blood sugar management tool.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Fifty years ago, people with type 1 diabetes were unable to test their blood sugars. They guessed how much insulin they needed based on their symptoms. Since then, diabetes technology has quickly evolved; for decades, patients have pricked their fingers and used glucose meters to test their blood glucose levels throughout the day.

Now, continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMs) are rising in popularity. These tiny devices are worn on the body and estimate patients’ blood sugars every few minutes, and readings can be viewed on a smartphone via Bluetooth. CGMs have been shown to improve diabetes management. They are especially useful for children, as parents can continually monitor their child’s diabetes while they are at school.

With the convenience of a CGM comes a hefty price tag. Out-of-pocket costs for CGM devices range from $1,000-$3,000 per year; this does not include the cost of insulin or insulin delivery pumps.

Children whose families cannot afford CGMs or live far away from health centers often go without this new technology. Most children with CGMs must visit their doctor every 3 to 6 months to continue their prescription; since rural families may struggle to attend follow-up appointments, patients may need to continue finger pricking to test their blood sugars.

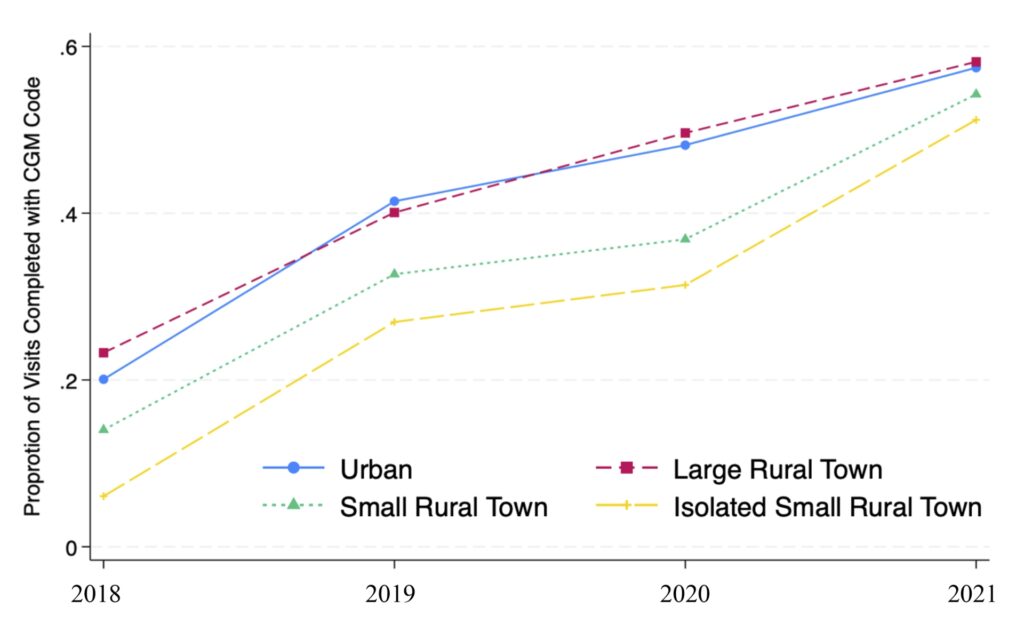

Daniel R. Tilden and colleagues studied CGM access among children in urban and rural areas of Tennessee between 2018 and 2021. All children included in the study attended clinics in the Vanderbilt Pediatric Diabetes Program. The researchers categorized each child’s home as urban or rural based on commuting area designations.

The graph above shows the proportion of health care visits that began or renewed CGM prescriptions. Urban areas (shown in blue) and large rural towns (shown in red) consistently had the highest proportion of visits that involved CGM prescriptions, while isolated small rural towns (shown in yellow) lagged behind.

Diabetes care continues to improve, but in addition to medical coverage, where a child lives affects their access to optimal treatment.