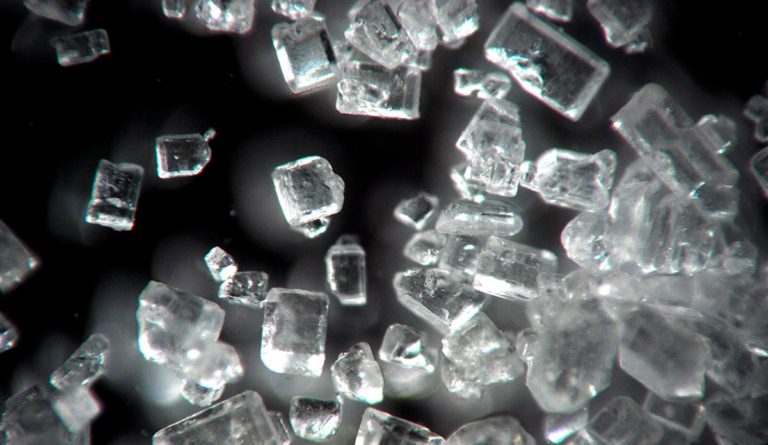

Can Sugar Substitutes Reduce the Risk of Obesity?

The current obesity and diabetes epidemics have sparked renewed interest in identifying alternatives to table sugar, but sugar substitutes currently on the market have not yet lived up to expectations.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Although sugarcane was domesticated some 8000 years ago in New Guinea, table sugar (sucrose) remained an expensive commodity until the 20th century. As the affordability of table sugar improved, its consumption increased steadily. Over 31 years (1978 to 2009), the price of sugars and sweets in United States cities lagged behind the price increases of fresh fruits and vegetables. This price differential may have encouraged people to consume increasing quantities of sugar sweetened beverages while decreasing their consumption of milk. Meanwhile mounting scientific evidence indicates that overconsumption of sugar is contributing to the rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity and diabetes.

Given this evidence, the American Heart Association advises women to limit their added sugars to fewer than 100 calories daily and men to fewer than 150 calories daily (approximately 5% of total energy intake). Similar guidelines have been proposed by the World Health Organization. The question of whether sweeteners would help in achieving these goals has to be methodically addressed.

Given this evidence, the American Heart Association advises women to limit their added sugars to fewer than 100 calories daily and men to fewer than 150 calories daily (approximately 5% of total energy intake).

The current obesity and diabetes epidemics renewed interest in identifying alternatives to table sugar that provide the gustatory qualities of sugar without the weight gain. Sugar substitutes and sweeteners currently on the market have not yet lived up to these expectations. Indeed, several epidemiologic studies have found a positive correlation between regular use of artificial sweetener and weight gain.

Some laboratory experiments have suggested that, when sweetness is decoupled from caloric content, there is incomplete activation of the food reward pathways, thereby increasing food seeking behavior. Another disconcerting finding is that commonly used non-caloric artificial sweeteners cause glucose intolerance through changes in the intestinal bacteria. Although these observations were made in laboratory mice, they provide a mechanistic explanation for the reported increased risk of diabetes associated with the widespread consumption of non-caloric artificial sweeteners.

Indeed, several epidemiologic studies have found a positive correlation between regular use of artificial sweetener and weight gain.

There are currently six non-caloric artificial sweeteners approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as food additives: aspartame, acesulfame-k, neotame, saccharin, sucralose and advantame. In addition, the FDA considers two high-intensity sweeteners to be GRAS (generally regarded as safe). The latter includes Luo Han Guo fruit extracts from monk fruit and high-purity (95% minimum purity) sweet ingredients of stevia leaves. Of note is that stevia leaf and crude stevia extracts are not considered GRAS and their use as sweetener is not permitted in the United States.

In addition to non-caloric artificial sweeteners there are two categories of nutritive sweeteners, namely sugar alcohols and some naturally occurring rare sugars. The sugar alcohols include sorbitol, xylitol, lactitol, mannitol, erythritol, trehalose, and maltitol. These sweeteners are slightly lower in calories than table sugar and their sweetness ranges from 25% to 100% of the sweetness of sucrose. They are common ingredients of “sugar-free” candies, cookies, and chewing gums as they do not promote tooth caries. However, when consumed in high quantities, they may cause gastrointestinal discomfort and diarrhea. Naturally occurring rare sugars vary in their caloric density. Some of these rare sugars, notably D-allulose, have been shown in animal experiments to have appetite suppressing activity and anti-glycemic activity that can reduce post meal blood sugar surges in humans.

Overall, current evidence links overconsumption of sugar with increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Given the limitations of popular alternative sweeteners and their potential harm, the need for identifying novel sweeteners with fewer health risks is pressing. Meanwhile limiting consumption of any sweetener may well be the best health advice. In this regard, replacing sugar sweetened beverages in school lunch menus with fresh fruits and vegetables as well as taxing sugar sweetened beverages would probably reduce the consumption of table sugar.

Feature image: Catalin Besleaga, Sugar (detail) used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0