Most Rural Hospitals in the U.S. No Longer Deliver Babies

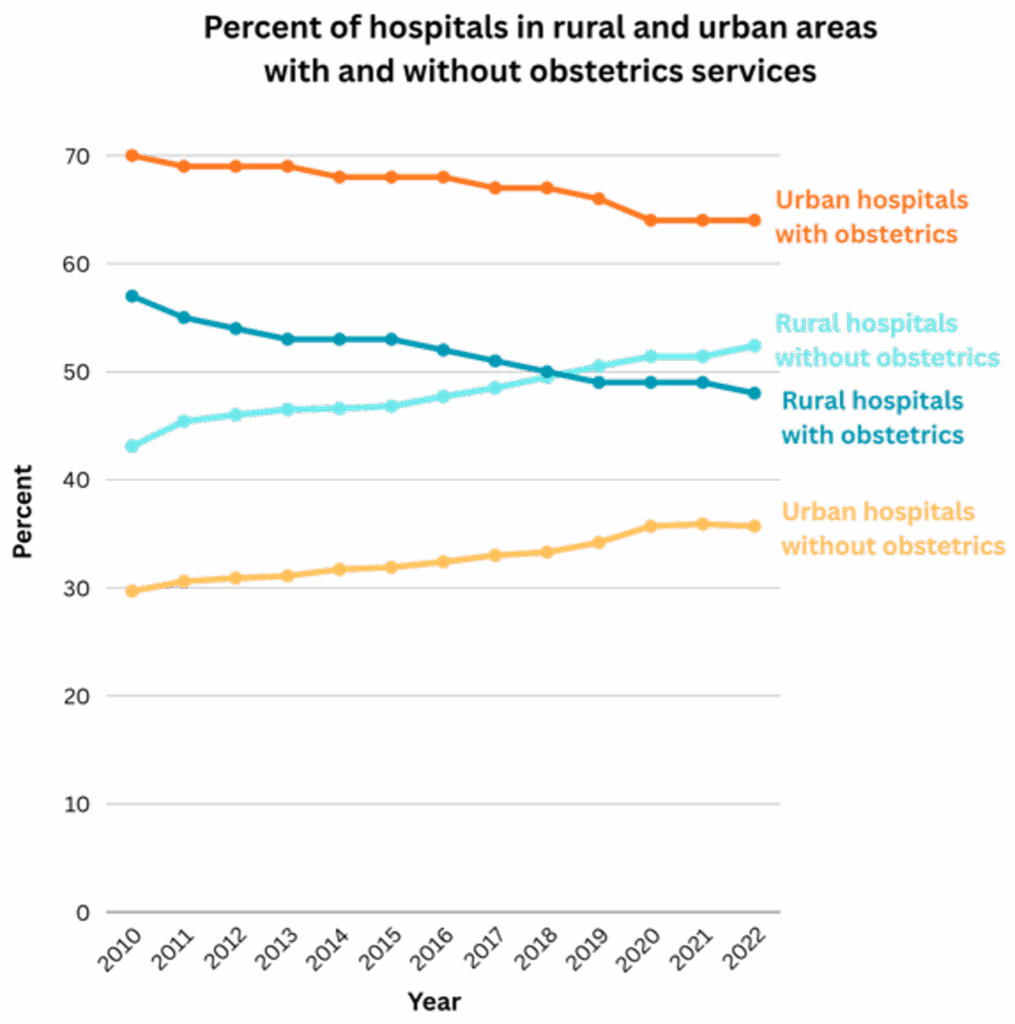

In 2010, 57% of rural hospitals offered obstetric services. By 2022, over half of rural hospitals no longer had labor and delivery care.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

It is a dangerous time to be pregnant in America. Abortion laws have become more restrictive, the maternal mortality rate has risen in the United States while declining in other high-income countries, and maternity care itself is disappearing. Between 2010 and 2022, many hospitals cut their obstetric services. From prenatal care to delivery, obstetricians play a vital role in keeping mother and baby safe. So why are hospitals cutting obstetrics? The motives aren’t medical. They’re economic.

Labor and delivery is an expensive 24/7 service in the U.S., requiring nurses, physicians capable of performing C-sections, and anesthetists to be on standby. Insurers reimburse far less for childbirth than it actually costs to provide care, and hospitals typically end up losing money. Some hospitals can afford to make up the difference with revenue from other services—but many, especially those in rural areas, can’t.

A new study shows how these financial pressures have reshaped where people give birth in the U.S. Katy Kozhimannil and colleagues counted the number of hospitals with obstetric units between 2010 and 2022, using American Hospital Association surveys and Medicaid records. The researchers tracked obstetric unit gains and losses at 4,964 hospitals, distinguishing rural and urban hospitals based on federal county classifications.

Rural communities began the decade with fewer maternity care resources and experienced larger and faster declines. In 2010, 57% of rural hospitals offered obstetric services, compared with 70% of urban hospitals. By 2022, more than half of rural hospitals, and a third in urban areas, had no labor and delivery care. And losses outpaced gains. Over the study period, 537 hospitals closed their obstetric departments, while only 138 opened new ones.

Pregnant people in rural communities already have a 9% higher likelihood of severe maternal morbidity or mortality than those in urban areas. But the loss of local obstetric services forces people to travel farther, which delays care and compounds the risks. These barriers have been linked to increases in emergency department deliveries, preterm births, and scheduled inductions and C-sections. Long travel distances are also associated with fewer prenatal care visits.

This problem persists because rural hospitals face financial barriers above and beyond those of urban hospitals. Hiring and retaining qualified staff is more difficult; a larger proportion of births are covered by Medicaid, which pays hospitals less than other insurers, and there are fewer births overall.

Other high-income countries have stabilized maternity care by nationalizing their health systems, regulating maternity reimbursement, subsidizing rural hospitals, or relying on midwives to manage low-risk births. While parts of the U.S. have piloted versions of these approaches, none have been implemented broadly enough to stem the wave of obstetric unit closures.

Because these units typically house the clinicians who provide prenatal care as well as delivery services, losing them means losing all local maternity care. Closing obstetric units may help balance hospital budgets, but when the nearest delivery hospital closes, a routine appointment can turn into a day’s drive, and labor can begin miles from care. These distances aren’t just inconvenient; they’re deadly, and every obstetric unit that closes pushes the country deeper into a maternal health crisis. Reversing this trend will require federal investment, workforce stabilization, and rethinking how maternity care is delivered in rural America.