Isabel Morgan

Isabel Morgan is the director of Birth Equity Research Scholars at the National Birth Equity Collaborative. She is also a PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, studying infertility epidemiology and equitable access to fertility treatment.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Isabel Morgan is the director of Birth Equity Research Scholars at the National Birth Equity Collaborative. She is also a PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, researching infertility epidemiology and equitable access to fertility treatment.

Public Health Post: What is the National Birth Equity Collaborative (NBEC)?

Isabel Morgan: NBEC is a small nonprofit organization committed to the advancement of birth equity, which means ensuring people have optimal birth experiences and increasing access to holistic and respectful maternity care before, during, and after pregnancy. Our mission is to ensure all Black mamas, their babies, and their village can thrive. We do this through research, policy advocacy, technical assistance, and training. We also have a transnational birth equity team working on expanding access and improving outcomes for Black women and birthing people across the globe.

In your role as the director of Birth Equity Research Scholars at NBEC, how do you and your team contribute to NBEC’s mission?

My team is unique from the other teams because we are responsible for creating support systems and providing leadership and development opportunities for Black women and femme doctoral or advanced degree students. We have students across many disciplines, such as engineering, anthropology, and clinical psychology. It’s going to take a multidisciplinary team with different perspectives and training to advance birth equity.

We currently work with the CDC to assess the collaboration between maternal mortality review committees, perinatal quality collaboratives, and community-based organizations. We’re also looking at how states assess the impact of interpersonal racism, discrimination, and structural racism on maternal deaths. Our second project is with the Perigee Fund, which focuses on maternal and perinatal mental health.

I’m also responsible for building our research and practice portfolio around infertility. There are many data gaps, and it’s hard to advocate for our issue areas when we don’t have the data we need.

Thinking about your work in infertility research, how does infertility fit into the reproductive justice conversation?

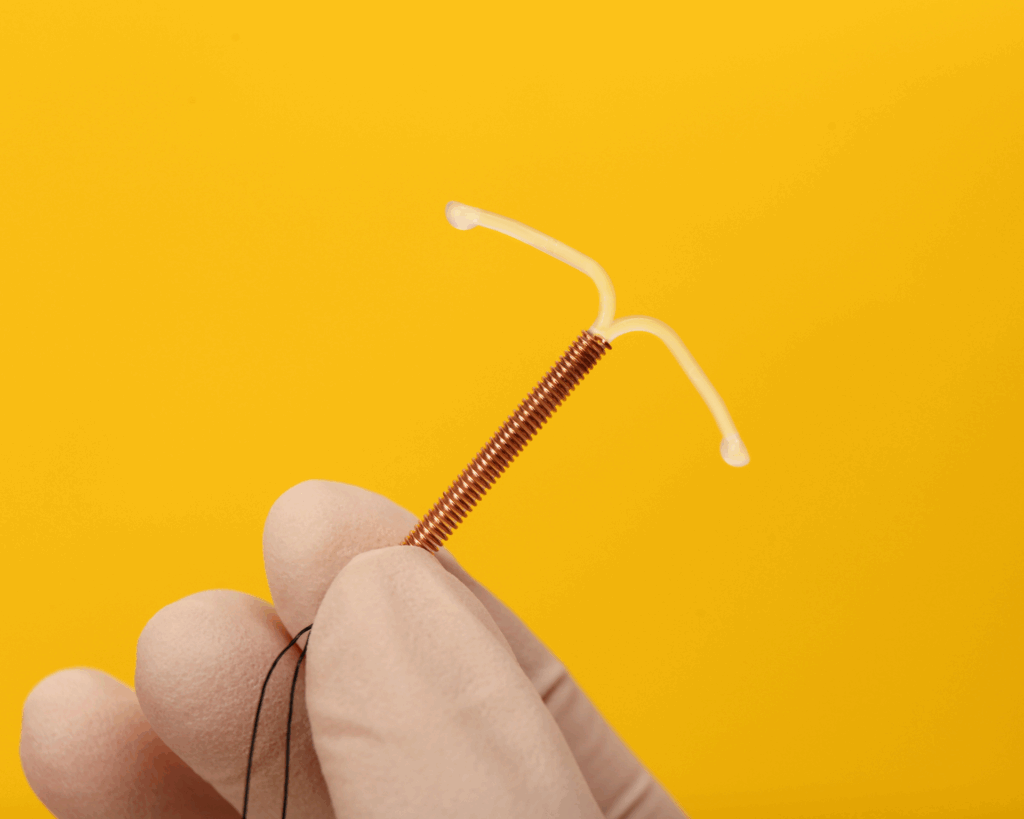

Within the reproductive justice movement, we focus on abortion, we focus on contraception, we’re now doing a lot of work around maternal deaths and maternal morbidity, but we still need to highlight infertility and fertility challenges as a reproductive justice issue. I don’t think it has legs quite yet. We’ve been socialized to believe stereotypes that trace back to slavery, specifically around Black women and reproduction.

The stereotype is that Black women are hyper-fertile, but this does not align with the data we have at the clinical and national levels. Black women have a higher prevalence of experiencing infertility, and there are challenges around accessing treatments. There are also inequities in our treatment outcomes. Black women are less likely to have a clinical pregnancy, less likely to have a live birth after undergoing intrauterine insemination (IUI) or in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, and are more likely to experience a miscarriage.

Why do you think infertility disparities aren’t discussed as much in the reproductive justice space, especially regarding Black women?

I think there’s silence and shame around it. There’s an assumption that you can have sex and have a baby whenever you’re ready. And when this assumption doesn’t go as planned, there is shame wrapped up in it. I think there is a unique shame Black women and Black people might experience, again related to this stereotype that we’re hyper-fertile. It also involves who society values and considers fit to be parents.

How are current national data collection methods for infertility limiting research?

The official definition of infertility is the inability to conceive after trying for 12 months if you’re younger than 35 and the inability to conceive after six months if you’re older than 35. The National Survey for Family Growth (NSFG) reports infertility based on behaviors like contraception use and sexual intercourse, but they only consider married and cohabitating individuals. The NSFG leaves out folks who are not married, not cohabitating, or are single. If we don’t have laws that allow same-sex marriage, NSFG also leaves out folks who are LGBTQ+. We’ll miss many people who desperately want to be a parent and might need fertility services, but don’t have a clinically defined, biological cause of infertility.

How can people get more involved with infertility advocacy?

People could support other organizations like ours, such as the Cade Foundation, Fertility for Colored Girls, or The Broken Brown Egg. Organizations like these focus on providing resources, emotional support, and even financial support to Black women or people of color and their families undergoing or seeking infertility treatment. The Broken Brown Egg also has podcasts so folks can learn more about their work, how they can donate, and what work is happening within their local community.

Photo provided