Urban Blight

A recent Urban Institute report shows that urban blight, defined as substandard housing, abandoned buildings, and vacant lots, is major stressor. Repairing neighborhoods can improve individual and community health and well-being, and even reduce gun violence.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

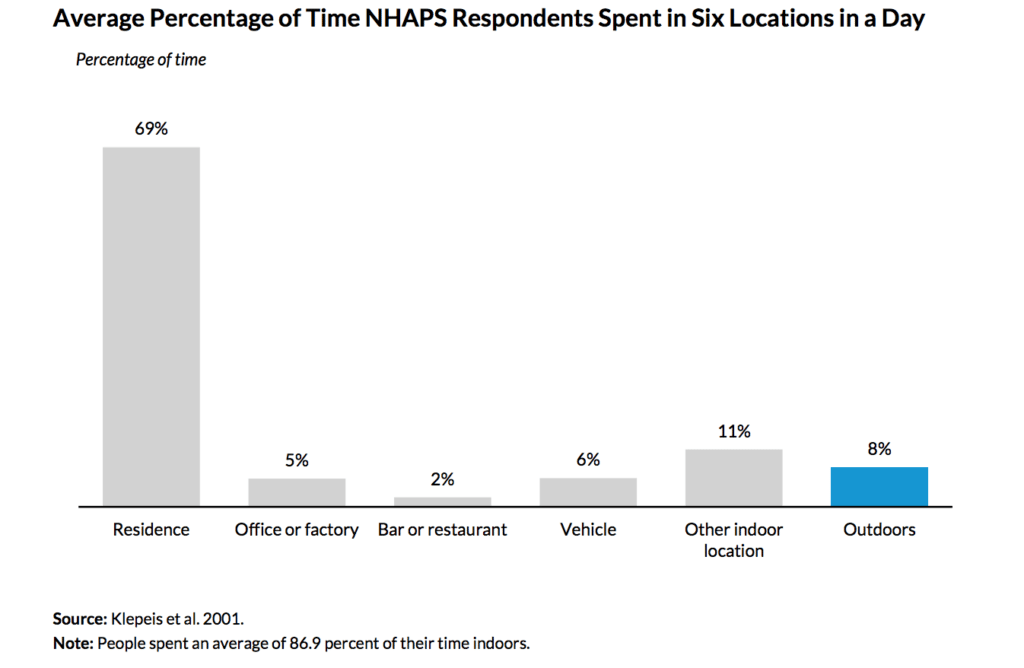

Yesterday’s databyte by Gilbert made a compelling connection between health and place. Simply put, a person’s zip code may have a larger impact than genetics on health indicators such as life expectancy. Yesterday’s map made it clear that rural areas are particularly unhealthy. But living in a city brings its own set of challenges. A recent Urban Institute report shows that urban blight—defined as substandard housing, abandoned buildings, and vacant lots—is major stressor.

Urban blight and health outcomes

Simply having a roof over your head is insufficient for the residents’ well-being and having a safe place to live. The Center for American Progress estimates that about 6 million homes have physical infrastructure issues: 6.8 million have high levels of radon, 17 million have high levels of indoor allergens, and 23 million contain lead-based paint. These substandard housing conditions lead to adverse health outcomes such as lung cancer, asthma, and negative cognitive and behavioral effects especially for children.

Where one sleeps is not the only influence on health outcomes. Neighborhoods filled with vacant or abandoned properties are linked to higher rates of mental distress, chronic illnesses, sexually transmitted diseases, and unhealthy habits. The broken window theory proposes that the vacant properties “create a climate of social and psychological disorder that attracts criminal activity and violence and becomes a breeding ground for vermin.”

Researchers have noted the detrimental effect vacant properties have on social capital. Lowered social capital makes it difficult for community members to advocate for their own neighborhood. It is a vicious cycle. Uncared-for space makes many neighborhoods unattractive, resulting in less investment in the community. Additionally, crimes that may occur on or around this property will encourage a feeling of helplessness. Residents will live increasingly isolated lives and will be less likely to step in to help prevent crime. In one study conducted in Philadelphia, residents thought that vacant land affected “community well-being by overshadowing positive aspects of the community, contributing to fractures between neighbors, attracting crime, and making residents fearful.”

Inextricable factors

There is no simple solution to the housing issues facing 95 million Americans. Affordability of housing is often the root of the issue. Residents accept substandard housing because it’s available for a rent or mortgage they can manage. An estimated 26% of renters spend more than 50% of their income on housing, well above the 30% that is typically acceptable to spend on housing. Even if substandard housing and vacant lots were remedied, expensive housing costs can siphon money from other life essentials, such as healthy foods.

Repairing neighborhoods

Cities across the U.S. have undertaken efforts to address urban blight. More than 6,000 vacant properties in Detroit have been transformed into urban gardens. Philadelphia’s LandCare program creates green spaces and fences previously vacant lots. A study on Philadelphia’s program demonstrates that its effectiveness even extends to reducing gun violence: the renovation of the lots resulted in a 5% reduction in gun violence, and replacing broken windows in abandoned houses resulted in a 39% decrease. Every dollar invested in improving urban blight resulted in $26 less spent on gun violence costs.

Urban blight is a complicated issue with many outside factors influencing the house, neighborhood, and residents. Therefore, researchers at the Urban Institute encourage a holistic approach, involving partners that can address all factors that contribute to the well-being of residents within a certain neighborhood. Policymakers should engage government agencies and community partners that advance community development, housing, education, and social welfare.

Feature image: Baltimore Heritage, Vacant rowhouses, 1212-1216 N. Gay Street, Baltimore, MD 21213. Photograph by Eli Pousson, 2017 February 8.

Charts from “Urban Blight and Public Health” by Erwin de Leon and Joseph Schilling