The Story We Are Not Talking About Enough

US life expectancy declined for the third year, a drop not seen since the 1918 flu pandemic, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

The Story We Are Not Talking About Enough

In 1918, a pandemic of Spanish flu infected approximately one third of the global population, killing between 20 and 50 million people. In the United States alone, more than 650,000 people died, enough to contribute to a decline in the country’s life expectancy. For a century, this was the worst decline in American health. Until this year. The National Center for Health Statistics reported that, between 2016 and 2017, US life expectancy dropped from 78.7 to 78.6 years. This marks the third consecutive year that life expectancy in the US has decreased.

We have not had a drop like this since the 1918 flu pandemic. What does our lack of attention tell us about how we think about health in this country?

One possibility it that we simply don’t know about these data. Perhaps we should have news headlines, “Our national health has taken a turn for the worse,” appear regularly until we reverse this trend.

Or perhaps we have come to accept the longer-term trend in which US life expectancy has lagged relative to other economically comparable countries. Perhaps knowing that our health is not terrific is simply the American condition. But, of course, it is not and our health was not always worse than our peer countries. As recently as thirty years ago we were in the top half of the pack.

Or perhaps we think that our collective national problems with health—addiction and suicide are the notable crises driving our falling life expectancy—are not my problem. If we spend enough money on our health, each of us is going to be fine.

Or perhaps we don’t know how to correct this slippage in life expectancy. We see the problem as too large, beyond our control, untenable.

If we continue to accept our collective poor health, it is in part because we are not paying attention to health the way we should be, and it is in part because we have accepted changes in the past 30 years—such as growing levels of income inequality—that have made our health worse. In the end, poor health for some will affect the health of many of us. Our chances of getting infectious diseases, of being a killed by a car while walking, of developing asthma due to secondhand smoke, all depend on the health of others around us.

Shouldn’t we then start paying attention to the worst American health deterioration in a 100 years?

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

SMALL TOWN ORGANIZING AROUND FOOD

High poverty rural communities often have limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables and have higher needs for nutrition assistance. Food pantries, the creation of local food policy councils (FPCs), and support from traveling “food coaches” may alleviate the food insecurity in small communities. These authors describe the efforts in six Midwestern states to improve the availability of healthy foods for pantry users. Alignment of policy, models of food distribution (preselected food box vs. food choice), and the connection of local food-assistance organizations is necessary but time-consuming and demands novel public-private partnerships.

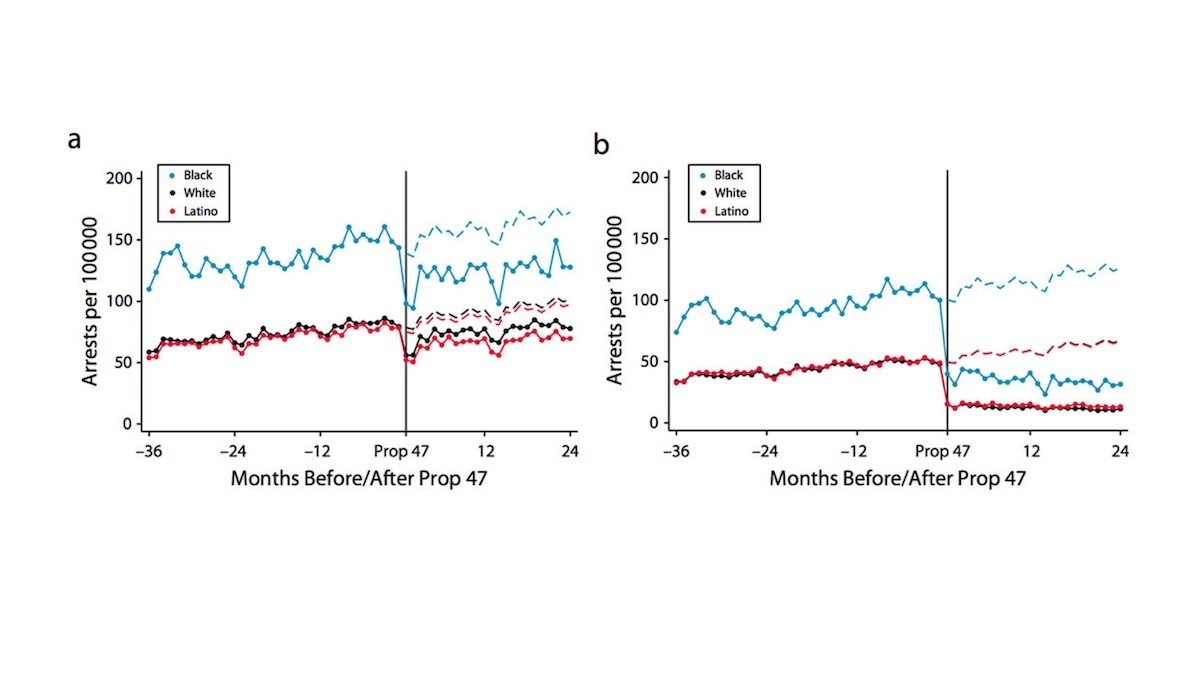

DRUG ARRESTS BEFORE AND AFTER PROP 47

In 2014, Californians passed Proposition 47, a ballot initiative that reduced certain drug-related felonies to misdemeanors. Prop 47 also focused money and resources on more serious offenses while investing the savings into treatment for substance use disorders.

Alyssa Mooney and colleagues used data from the California Department of Justice’s Monthly Arrests and Citations Register and the American Community Survey to look at both total drug-related arrests and differences due to race and ethnicity on drug-related arrests before and after the passage of Prop 47.

The figure above shows both total drug arrests (left graph) and felony drug arrests (right graph) in California before and after Prop 47 was implemented. The dashed lines show expected arrest rates if Prop 47 had not passed.

There was an immediate drop in felony arrests after Prop 47 passage. Black individuals did not gain the full benefit of the felony to misdemeanor change because certain drug offenses, such as drug selling, were not reclassified, disproportionately affecting this group. — Chrissy Packtor, PHP Fellow

Graphs from “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Arrests for Drug Possession After California Proposition 47, 2011–2016” Alyssa C. Mooney, Eric Giannella, M. Maria Glymour, Torsten B. Neilands, Meghan D. Morris, Jacqueline Tulsky, and May Sudhinaraset, Am J Public Health. 2018;108:987– 993.