Spending Too Much On the Wrong Things

Americans spend half as many days in hospital as do persons living in other high-income countries. We take fewer pills per person.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Spending Too Much On the Wrong Things

Americans spend half as many days in hospital as do persons living in other high-income countries. We take fewer pills per person. We log fewer office visits and have fewer doctors per capita. Yet we spend 2-3 times as much as other countries on health care and have poorer health outcomes. In 2017, we spent $3.5 trillion. Why? Because we overpay.

If spending equals utilization times price, then we can reduce the amount we spend by reducing either utilization or price. In a delivery care system that is already quite lean, utilization is hard to ratchet down much further. Sure, we can better coordinate care when an ill person transitions between facilities. Yes, we can cut back on unnecessary or repetitive testing.

But, if there is ever to be any real prospect of reducing our spending as a country, the real action has to be on price. Yet when any policymaker mentions price control, everyone looks away, and the conversation swings back to utilization, about reducing the number of “superutilizers,” or it turns to “value,” the newest buzzword.

Talking about overspending suggests that certain partners in the health system are charging more than they should. Since about one third of our health care spending is related to hospitals (equipment, supplies) and another 20% is paid to health care providers, these are the obvious culprits. Fifteen years ago Anderson et al. noted that the difference in health care spending here compared to other countries “is caused mostly by higher prices for health care goods and services in the United States.” This was reinforced in a recent paper that concluded much the same thing.

Not news, but still notable. Health care spending is expected to rise more than 5 percent annually through the next decade, or about 1 percentage point faster than economic growth. Because we overpay for goods and services, it will become more and more difficult to pay for programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and for employers to keep financing medical coverage for workers and their families.

But there will be a massive fallout if we spend less. Workers (employed by hospitals and medical device companies and pharmaceutical firms and doctor groups) will lose jobs if prices (hence payments) go down, and these medical jobs now drive the economies of large cities and small rural towns alike.

But are we getting our money’s worth in the current system? Our health outcomes are inferior to those citizens of Canada and European nations enjoy. If our national health spending is a zero sum, if we spend less on hospitals and clinicians who care for us we could spend more on the social services required to prevent or reduce illness, to make our entire population healthier. Would that be worth the price of taking a long, hard look at our spending?

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

COLLEGE DRINKING: STAGGERING TO THE ED

Tens of thousands of American college students visit the emergency department (ED) after bouts of drinking. This study found that 10% of all ED visits in a large university health system involved alcohol intoxication. Two thirds of these alcohol-related ED visits had an additional diagnosis, with injuries (24%) the most common condition. The rate of alcohol intoxication as a proportion of all ED visits rose more than 50% from 2009–10 to 2014–15. The increase was greater among female students, students below 20 years of age, Asian students, and student athletes.

NAVIGATING THE HEALTH CARE SEA

Patient navigators (aka case managers, care coordinators, community health workers, health coaches) are persons with or without a healthcare-related background who engage patients on an individual basis to help them access care, follow treatment guidelines, and pursue self-care. This review of 67 papers across chronic diseases looked primarily for improvements in processes of care. Most navigators are lay people and most communication is done by phone. Two thirds of studies reported improvement in primary outcomes such as disease screening and adherence to follow-up appointments. Few studies of navigators have assessed patient experiences, clinical outcomes, or costs.

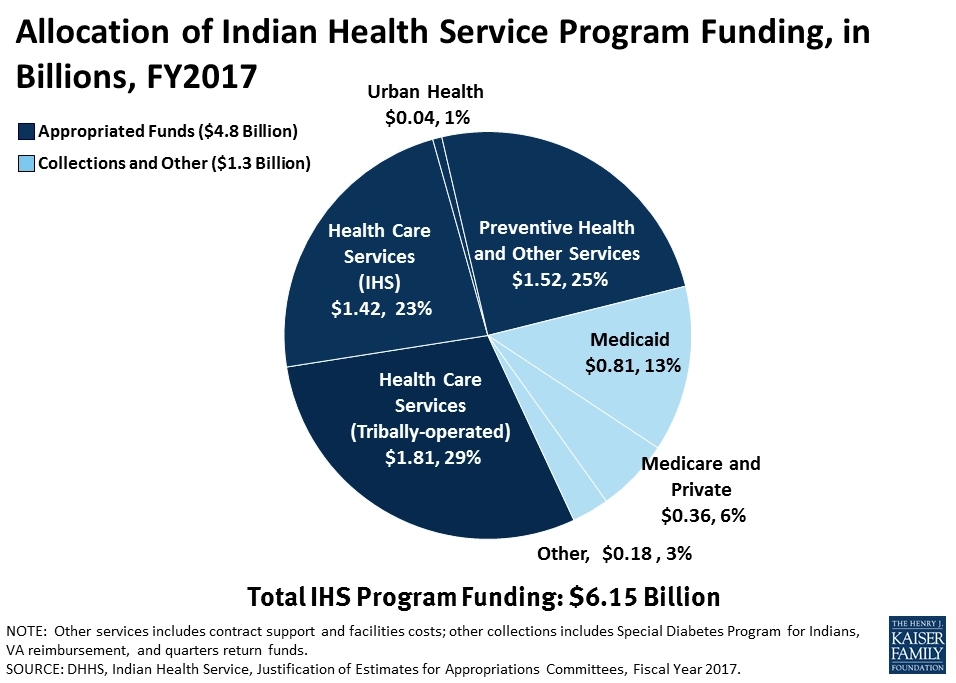

LIMITED HEALTH FUNDING FOR AIANs

American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AIANs) can receive free health care from facilities managed by the Indian Health Service, federally recognized Tribes, and urban Indian health programs. All receive money from the funds allocated by Congress to the Indian Health Service. The funding is limited, however, and if more is required, some services may be prioritized over others or rationed.

The image above depicts the findings of a recent report on AIAN health. In 2017, Congress provided $4.8 billion to all AIAN health care services, and $1.3 billion came from third-party sources like Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance, and the Veterans Administration. Urban Indian health programs only received 1%, or about $40 million, of this funding. AIANs who do not live on federal reservations and are not members of federally recognized Tribes are unable to receive care from the Indian Health Service or Tribe-operated programs, and may turn to the urban Indian health programs for services.

The uneven distribution and disproportionately small amount of funding that these programs receive in comparison to other services indicates that some AIAN health needs remain unmet. Those who rely entirely on the Indian Health Service may not have access to primary care. Unlike Indian Health Service and Tribe-operated facilities, urban Indian health organizations cannot contract with the Purchased/Referred Care program, which fills gaps in care with private providers. To improve access to care, urban Indian health programs must receive similar or greater support in comparison to other AIAN health care services, and funding mechanisms for such broad programs must improve.

—Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Graphic: Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid and American Indians and Alaska Natives,” Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Foutz Published: Sep 07, 2017