Should Black Boxes Be Welcome in Medicine?

Medicine embraces novel technical approaches to improve care. But what if those technical approaches bring greater scrutiny to clinical work?

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Should Black Boxes Be Welcome in Medicine?

It has become an article of faith that technology will improve the practice of medicine in coming decades. Medicine enthusiastically embraces novel technical approaches that may improve patient care. But what if those technical approaches bring greater scrutiny to clinical work? What if they may cast a harsh light on work that medicine typically does behind closed doors?

Such questions emerge as efforts grow to introduce “black boxes” to surgery.

When an airplane goes down, there is an urgent search for the plane’s black box. The black box contains both the audio recording of all cockpit discussion as well as a recording of flight instrument readings. These two flight recorders are required by international regulation and together offer the best possibility of learning what happened in the minutes preceding any aviation accident or incident.

This kind of recording technology that captures medical conversation and physiological parameters, allowing for post-surgery analysis, is just making its way into the world of medicine. Early reports suggest that intraoperative error events are far more frequent than previously noted and a high number of operating room distractions contribute. Black box recording devices would bring a new transparency to what actually happened during adverse events, allowing us to improve our surgical procedures.

But the operating room is a sacred space. Its sterilized choreography and chatter have never before been scrutinized in this way. The work of surgeons—detailed, immodest, sequestered, and focused on a small part of the body of a single unconscious patient—is the labor of mortal lessons.

So the new technology raises important questions. Will surgeons (and other health professionals) be put in malpractice jeopardy by such new information? Will patients and their families become more likely to sue? Will more information undermine patient trust?

Surgical safety depends on team dynamics and communications, technical issues, and an alertness and rapid response to a patient’s trouble. Will constant surveillance produce a different kind of accountability and therefore a different level of stress? Will surgical staff be more likely to speak up when they see something amiss?

These questions will require sober assessment. But at heart, we are an information culture, and medicine aspires to create a culture of continual improvement. We can imagine black box technology entering medicine widely over the next years, beyond surgical suites and into delivery rooms where maternal mortality is rising, and where we might study what goes wrong, identify solutions, share lessons learned.

That seems right for the public’s health.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

THE CHILDREN OF PRISONERS

Racial and ethnic differences in sexually transmitted infection (STI) and HIV rates emerge during adolescence and widen during young adulthood. Substance use is a critical behavioral determinant of STI/HIV risk. These authors considered whether parental incarceration also contributes to both substance use and STIs. They reported that children under 18 whose parents are incarcerated are at higher risk for STI/HIV in both adolescence and adulthood, with the strongest effects among non-Whites. Black children under 8 years old whose parents were incarcerated were twice as likely to use marijuana as adults and four times as likely to use cocaine. Half of all American children who have an incarcerated parent are Black. Children impacted by parental incarceration are in greatest need of substance use and STI/HIV prevention and treatment.

FINANCIAL STRESS AND TRYING TO QUIT SMOKING

Despite national declines in smoking rates, 26% of those living below the poverty threshold continue to smoke. The added expense of smoking may contribute to the financial strain experienced by persons with lower income. Yet tobacco use increases during times of financial stress; fewer smokers quit and those who do face a greater likelihood of relapse. These authors examined whether financial strain in low-income adults increases the severity of perceived post-quit nicotine withdrawal symptoms, making it more difficult not to relapse after a quit attempt. They found that greater financial strain exacerbated post-quit anger, anxiety, and sleep disturbance, which contributed to a return to smoking. The authors speculate that behavioral strategies, such as offering financial incentives early in a quit attempt or providing financial education in conjunction with nicotine replacement therapy, may alleviate financial strain, reduce withdrawal symptom severity, and improve smoking cessation outcomes.

PARTICULAR PARTICULATES

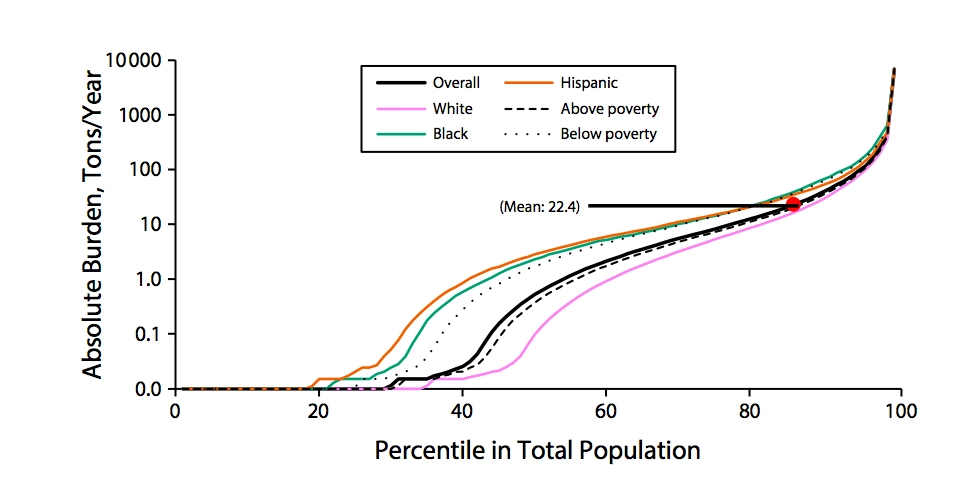

Racially or ethnically marginalized and poor communities in the United States are more likely to have nearby landfills and industrial sites producing pollution than majority White, affluent communities. These facilities emit harmful air particulates that impact lung and heart health. Particulate matter (PM) in the air is a combination of solid and liquid pollutants. In general, the smaller the particles, the more harmful to health. An April 2018 report offers the latest findings on the health impacts of disparate exposure to PM2.5, or particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter.

The figure above depicts the distribution of the PM2.5 burden, or the average tons of PM2.5 emitted per year at close proximity, by race, ethnicity, and poverty status. Hispanic and Black people tend to have a higher PM2.5 burden than their White counterparts. Also, those below the federal poverty line experience more exposure to PM2.5 than those with higher incomes. Fifteen percent of the population is exposed to more PM2.5 per year than the average 22.4 tons. This includes all groups.

PM2.5 is associated with a higher risk of illness and death, and Black populations have a higher prevalence of heart disease and asthma than White populations. The report’s findings confirm previous research documenting disproportionate exposure to harmful particulate matter in communities of color.

Graphic: FIGURE 1—Distribution of Absolute Burdens of PM2.5 Emissions From Nearby Facilities in the 2011 National Emissions Inventory, Stratified by Race/Ethnicity and Poverty Status: American Community Survey, United States, 2009–2013. Ihab Mikati, Adam F. Benson, Thomas J. Luben, Jason D. Sacks, Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, “Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status”, American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 4 (April 1, 2018): pp. 480-485. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304297