Public Health and the President's Racism

President Trump has a history of statements that suggests he harbors racist sentiments and of actions that would back up these same sentiments.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Public Health and the President’s Racism

President Trump has a history of statements that suggests he harbors racist sentiments and of actions that would back up these same sentiments. He seemed to lay to rest any doubt about his inclinations in reported statements in the Oval Office that the United States should not be granting admission to residents from “shithole” countries.

That the President of the United States used such terminology appropriately resulted in a collective furor. Vice President Biden in a tweet suggested that “It’s not how a President should speak. It’s not how a President should behave. Most of all, it’s not what a President should believe.” There seems little question the President’s words fall far beneath the level of dignity and decorum one might expect from the leader of the world’s oldest constitutional democracy. But why does the President’s racism matter for the health of the public?

To answer this question, one needs to understand how health is produced. Health in populations is the product of the social, economic, and cultural context in which we live. Cultural context determines the social norms that bind us and that in turn determine our behaviors and their consequences.

On the positive side, changing norms can promote health. For example, this was abundantly evident in the decline in cigarette smoking and motor vehicle deaths in the United States during the latter half of the twentieth century; the former was attributable to change in public perceptions about smoking and the latter to a widespread acceptance of vehicular and road safety measures.

The office of President wields perhaps the world’s largest megaphone. The President’s words and actions can change the norms that bind us, and empower elements of hate in society to act out their worst impulses. This results in more hate crimes, more exclusion of minority groups from salutary resources, and a return of growing segregation of racial groups that in and of itself generates inequitable access to healthy resources and poor mental and physical health.

The President’s actions have, unfortunately, backed up his words. For example, the administration’s attempt to ban immigration from predominantly Muslim countries, and its rescinding of Obama administration guidance to schools to enforce the right of transgender children to use whichever bathroom they choose may, at face value, affect only a small number of people. But they enable the chiseling away at social norms that value inclusiveness and diversity, tolerance and accommodation to those who are otherwise different than the mainstream.

Racism is morally repugnant and needs no link to health to be so. And yet racist comments make discrimination acceptable and cruelty mainstream. Trump’s racist words offer cover for policymakers intent on denying the existence of racial disparities in care, and thereby impede the institution of possible remedies. Further, his words lower the self-regard of millions who, feeling threatened or renounced, do not care for themselves because they believe others have little interest in their health and lives.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

TWITTER STIRS THE ANTI-IMMIGRATION POT

In 2010, Arizona passed the “show me your papers” law–formally known as SB 1070. It gave law enforcement officers the ability to stop and detain individuals on the basis of “reasonable suspicion.” An analysis of the Twitter response showed that the law’s passing seemed to embolden those with negative attitudes towards immigrants and native-born ethnic minorities to publicly voice their opinions with greater force and frequency.

MENTAL HEALTH AND COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

In a 5-year span, the Mississippi Gulf Coast experienced the devastating effects of both Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Research in these communities finds that people who perceive their community as resilient may contribute to the actual revival of their community. Optimism and personal psychological resilience tend to strengthen a community’s ability to adapt and recover. In effect, communities that invest in mental health may be better positioned to adapt and recover after disaster.

THE DOCTOR MAY NOT BE IN

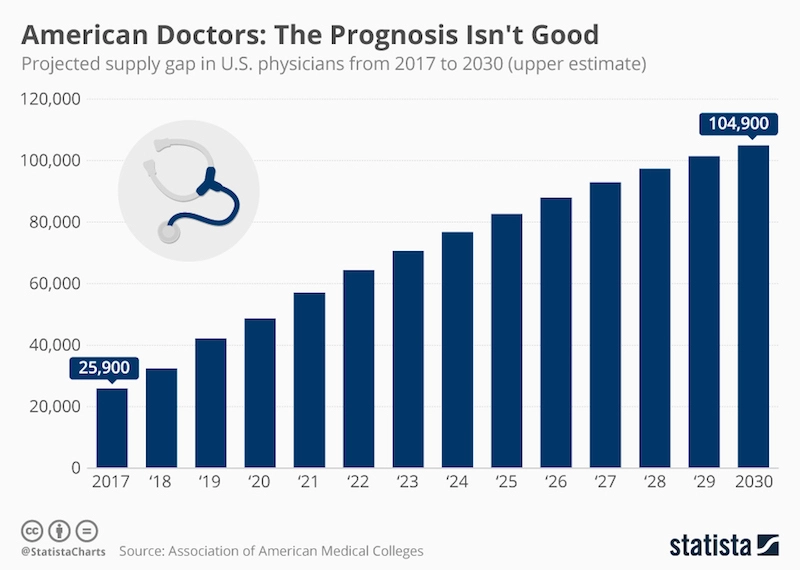

For the past three years, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has projected that demand for physicians in the United States will increasingly outpace supply by 2030. Their 2017 update projects an even more pressing shortage than in past reports. The U.S. population is expected to grow by 12% from 2015 to 2030, with the 65 and older population experiencing significantly more growth (55%) than their 18 and under counterparts (5%). Physician supply is largely expected to remain consistent. The healthcare system faces the challenge of training an extra 40,800 to 104,900 new doctors over the coming decade to meet the projected deficit, with specialists and surgeons in especially high demand.

An aging population means an increased demand for physicians who treat the elderly, but of course, doctors are aging too—according to the report, one-third of currently active physicians will be at retirement age within the next ten years.

The report also presents the ideal scenario in which underserved or uninsured populations gain equal access to health care and insurance—a phenomenon the AAMC calls “health care utilization equity.” Projections for physician need increase by an additional 35,000 to 97,000 depending on increases in coverage. Policymakers must be aware that increasing the number of people with insurance does not necessarily increase access to care if there are not enough providers.

Graph from Statista.com, American Doctors: The Prognosis Isn’t Good, by Niall McCarthy, Mar 23, 2017