Names Matter in the Opioid Epidemic

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Names Matter in the Opioid Epidemic

A quick survey of any number of general media reports about drug use will readily find mentions of “addicts” who use opioids. Casual conversations label those who use drugs as “junkies.” We are accustomed to using language to distance ourselves from those with substance use problems, making sure we mark those who use drugs as “the other,” not like us.

Erving Goffman, one of the giants in psychology of the twentieth century defined stigma as “The phenomenon whereby an individual with an attribute which is deeply discredited by his/her society is rejected as a result of the attribute. Stigma is a process by which the reaction of others spoils normal identity.” That is exactly what we have done with drug use and drug users. We have used nouns to label those who use drugs so that they are discredited as a result of their drug use, spoiling their normal identity. In research we had carried out nearly two decades ago, we showed that substance users feel more marginalized because of their drug use than any other self-identification.

Little has changed in the ensuing two decades. The opioid epidemic now kills more people annually than the HIV epidemic did at its peak, the firearm epidemic at its peak, or deaths from motor vehicles at their peak. And yet, despite near-saturation media coverage of the problem, limited resources have been made available by the Trump administration to tackle the epidemic. Surely part of the challenge is our ongoing stigmatization of those who use drugs. Because those who use drugs are the other, and could not be us. Continued use of marginalizing words in mass media echo this distancing, reinforcing the abnormality of “them,” “those” who use drugs. Names have the power to separate.

But the current epidemic has taught us that we all know someone who has developed a drug problem. It seems like a small step, but using the right language, always, to talk about drug use is a step toward helpful description, toward making it clear that opioids are our collective problem and worthy of investment that can turn the tide on the epidemic of our time.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

PILL MILLS AND THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Florida in the mid-2000s dispensed more oxycodone than any other state, in part due to pain clinics with lax prescribing requirements (no medical exam and ample choice of drugs) called pill mills. After major law enforcement efforts and stricter regulations on opioid prescriptions, Florida saw over a 50% drop in pain clinics, although many continue to operate.

UNTREATED TB ENDANGERS MIGRANT WORKERS AND STALLS TB ERADICATION

The U.S. agricultural industry is fueled almost entirely by the work of migrants and seasonal laborers, three-quarters of whom are foreign-born. This group holds the highest risk of tuberculosis exposure and transmission (66.5% of all U.S. TB cases), but is perhaps the least likely to seek testing and treatment due to cost, convenience, lack of culturally appropriate services, and fear of deportation or punishment. Accessible treatment for this high-risk, sometimes hidden, population is necessary to eliminate TB in the United States.

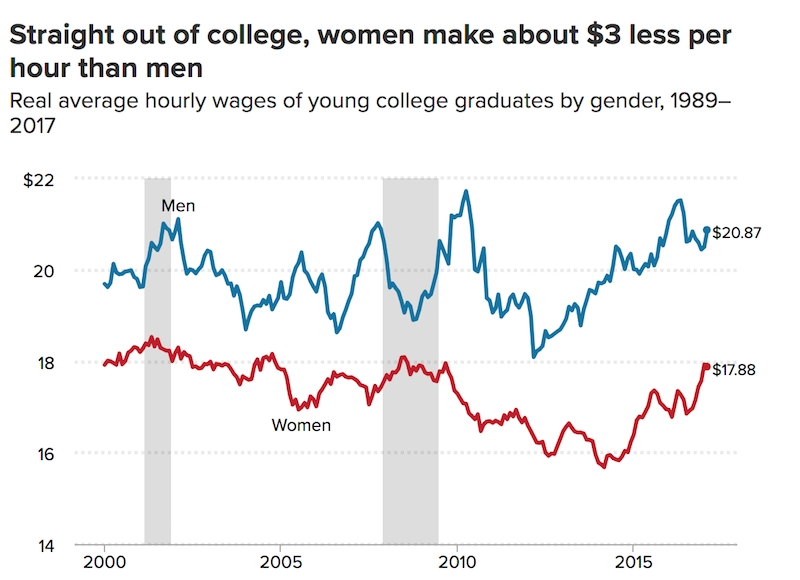

SAME RESUME, DIFFERENT PAY

The gender pay gap even extends to women shortly after college when they have similar experience and qualifications to their male counterparts. Men between the ages of 21 and 24 with a college degree are paid an average hourly rate of $20.87. Women are paid $17.88. In other words, women make $2.99 less on average per hour than men despite having exactly the same amount of education and usually similar working experience. This is an annual difference of $6,000.

While the pay gap between male and female high school graduates has lessened since 2000, the gap between recent college graduates has increased. This is especially remarkable as women earn their bachelor’s degrees at a higher rate than men: 20.4% of women between the ages of 21 and 24 have a bachelor’s degree compared to 14.9% of men. —Qing Wai Wong, PHP Fellow

Graph from Economic Policy Institute, Straight out of college, women make about $3 less per hour than men, Economic Snapshot, Elise Gould and Teresa Kroeger, June 1, 2017.