Invest in Health, Not Death

We all die and, despite some fanciful aspirations to the contrary, we will all keep dying into the future. Our daily routines keep us closed off to this fact.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Invest in Health, Not Death

We all die and, despite some fanciful aspirations to the contrary, we will all keep dying into the future. Our daily routines keep us closed off to this fact. Death’s inevitability suggests that we should keep it in our sights as we think about the public’s health. There are three areas which might fruitfully draw our attention.

Once we accept that we are going to die, how we spend our money and our time on the business of health begins to shift. At core we should aspire to die healthy. That means focusing our energy on creating a world that maximizes health, not one where we invest our resources into the last few months of life, aiming to fight death at all cost. This would represent a radical shift in how we think about our limited health investment dollars. Perhaps death can help focus our mind on living better, on the conditions that we need to create to generate health, rather than asking serial medical specialists to tackle symptom after symptom until we die.

It seems important that we not neglect the experience of dying itself. We all wish to die with dignity, and yet our collective focus on creating the conditions for that has been lacking for decades. Two out of three Americans do not have advance directives that guide what treatments they receive if they are sick, and cannot communicate the end-of-life care that they want. Redoubling our conversation about how we manage our dying can perhaps get us much further on this front.

The dead leave behind the grieving, and the grieving have a burden of poor health that is linked directly to the death of their loved ones. Sudden unexpected death of a loved one is the largest contributor, for example, to post-traumatic stress disorder in populations. Death leaves behind lonely older adults, now socially isolated, and themselves at higher risk of dying soon. Death creates a population health challenge for the living, one that is foreseeable and perhaps preventable.

Our squeamishness in talking about death is entirely natural. But it remains our collective role to elevate issues that influence the health of populations; death is indeed one of them. Perhaps recognizing the inevitability of death can guide us towards ways in which we can live healthier, die with dignity, and protect our loved ones when we do die.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

WHO BUYS MARIJUANA?

In 2014, four states and the District of Columbia legalized non-medical, retail marijuana for persons over 21. Although marijuana remains an illegal Schedule 1 drug under federal law, an estimated 35.1 million (13.2%) Americans aged 12 or older reported using marijuana in the past year. Who’s buying it? Approximately 18.5 million Americans aged 12 or older reported buying marijuana, which includes 1.8 million individuals aged 12–17 and 16.7 million persons aged 18 and older. Males and heavy marijuana users were more likely to buy. Six states (Mississippi, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Mexico, and Florida) had significantly higher percentages of individuals who reported buying marijuana compared to the national average. During the study period (2010–2014), none of these states had legalized retail sales of marijuana for non-medical use. As state-based marijuana legalization continues to evolve, it will be instructive to monitor recruitment of new marijuana buyers, particularly vulnerable populations such as youth.

THE DANGERS OF HOMELESSNESS

Every year, nearly 16 million American children see their mothers hit, kicked, or burned. Witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) affects a child’s health, development, and academic performance. Children growing up with periods of homelessness or housing instability are at risk for many of these same injurious outcomes. Women experiencing IPV are four times more likely to experience housing instability or homelessness, placing children at double risk. The authors interviewed forty-two mothers who were IPV survivors enrolled in a Safe Housing program that provided emergency shelter, scattered site transitional housing, and flexible funding. Mothers were interviewed three times over a six-month period about their children’s and their own safety and housing stability; 95% of participants were housed at the six-month interview when mothers described improvements in children’s stress levels, mood, and behavior. Mothers note the symbiotic relationship between their own stress and well-being and that of their children. Flexible funding to assist domestic violence survivors with their housing collaterally impacted the safety and achievement of two generations.

DEATH RATES VARY AMONG MEDICARE BENEFICIARIES

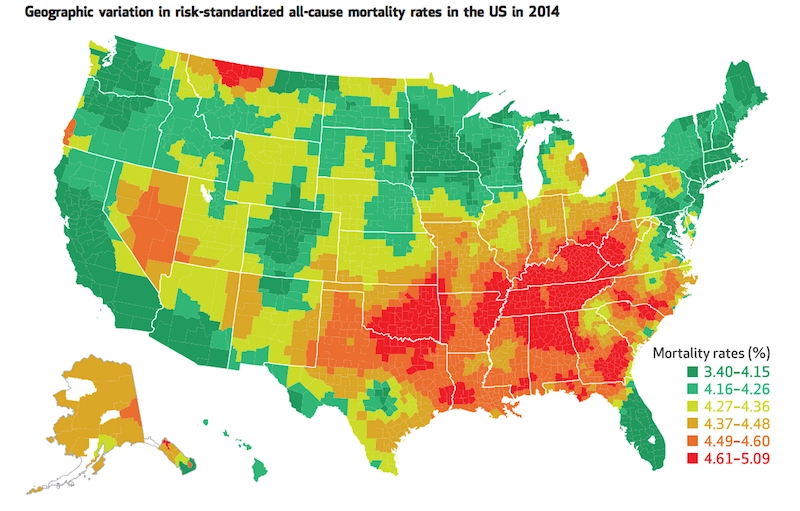

A January 2018 article in Health Affairs reports findings from a study that set out to identify areas in the United States with high numbers of deaths among Medicare beneficiaries.

The figure above depicts 2014 mortality rates from all causes for Medicare enrollees aged 65 or older by county. Marked red on the map, the highest mortality rates were found largely in the Midwest and South. Additional high mortality hot spots were identified in northern Montana, Nevada, and small pockets of Alaska, Oregon, and Utah. Similar regional trends were reported in 1999, though overall mortality rates declined from 1999 to 2014.

Over fourteen million Medicare beneficiaries consider these 820 hotspot counties home. The study found that, compared to other areas in the country, these high priority areas have relatively more non-Hispanic White and Black residents with lower income and education levels, and higher unemployment rates.

This study is the first to provide a geographic breakdown of mortality rates among Medicare beneficiaries. Policymakers can use these important data for targeting resources to address poverty and other social drivers of health, improve health care quality for older adults, and reduce disparities. —Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Feature image from “Geographical Health Priority Areas For Older Americans,” Harlan M. Krumholz, Sharon-Lise T. Normand, and Yun Wang, HEALTH AFFAIRS 37, NO. 1 (2018): 104–110 ©2018 Project HOPE—The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0744