Guns and Suicide

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Guns and Suicide

Suicide is one of the very few causes of death that have remained stubbornly steady over nearly the past century. A recent CDC report showed that suicide rates have risen about 30% in the United States since 1999. This report revealed an increase among all sexes, racial/ethnic groups, and all ages; in 2016 there were nearly 45,000 suicides in the US. With the recent increase adding fuel to our concern, suicide is now the tenth leading cause of death in the country.

Suicidologists have long noted that there is no single cause of suicide. Although those with medical illness are at higher risk of suicide, as are those with a substance use history, fully half of all suicide deaths have no known history of a mental health diagnosis. Reflecting this, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention calls for a broad range of approaches at the individual, family, and community level.

We have no doubt the National Strategy’s prevention goals, which move in many directions at once and require resources and new services, would make a difference over time. What if, as a first step we focused on something quite specific? What if we focused on limiting the means to commit suicide?

We can learn here something from South Korea where suicide rates have long been higher than other high-income countries. Suicide by pesticides accounted for more than a fifth of all suicides in the country in the 2006–2010 time period. Korea banned the sale of paraquat—the leading pesticide—in 2012, and this was followed by an immediate decline in suicide rates across all groups.

The success of such an effort rests on a simple observation—maybe close to half of all suicides are acts of impulse, decided within the hour, if not a few minutes, before the suicide itself. This means that having access to lethal means matters enormously. And lethality varies between means. The likelihood of a successful suicide by drug overdose is less than 10 percent; the likelihood of successful suicide by gun is more than 90 percent. That means that the impulse to suicide is much more likely to succeed with guns around.

It is then not surprising, given how many guns we have in the country, that guns account for about half of all suicides—more than 22,000 deaths in 2016—in the latest CDC report, far more likely than the next nearest cause.

There are plenty of reasons for gun safety measures in the United States. Surely as we discuss suicide, measures to limit the role of guns should be part of the national conversation.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

HOME IS WHERE THE ASTHMA IS

We have long known about associations between Black race, higher rates of pediatric asthma, and worse asthma-related consequences. This asthma-race connection is not accounted for by education or income, or other known factors like smoking, but rather is explained in large part by housing. These authors found that poor housing quality, specifically cracks in walls/floors/windows, broken plumbing, or exposed wires, was strongly associated with asthma and emergency room visits for asthma. Home ownership, which likely translates to greater attention to home safety, mitigated racial differences.

CARING FOR THE CARERS

An increasing number of Americans spend time helping or taking care of a relative or friend who has chronic illness. Half of these “informal” caregivers are over age 50, two-thirds are women, and the burden of care often has effects on working-aged caregivers’ labor force participation. This study reports that the 17.1 million women who provide at least 20 hours of informal care per week are 1 to 3 percentage points more likely to retire relative to other women. While some retirees may return to the workforce, if the expectation is that these individuals will not retire but instead work longer at some capacity (to secure Social Security benefits) while providing this care, there should be an increase in the financial supports available to working caregivers.

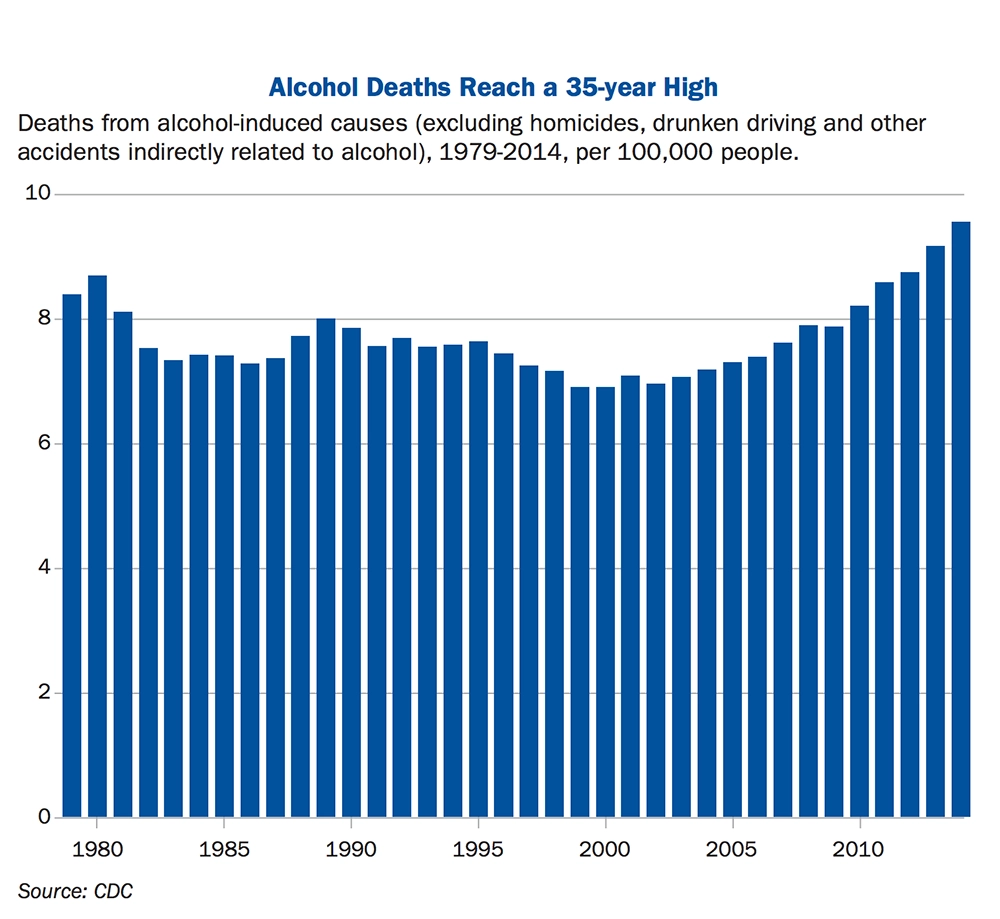

ATTENTION: ALCOHOL DEATHS STILL RISING

In November 2017, the Trust for America’s Health and Well Being Trust released a report called “Pain in the Nation: The Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Crises and the Need for a National Resilience Strategy.” The report covers three crises, but alcohol’s increasing role in the cause of death in the past couple of decades requires attention.

The report points out that liver diseases, alcohol poisoning, and other diseases account for 33,200 alcohol-related deaths in the last year. If car crashes—30% of which are alcohol-related—and other injuries are factored into the overall death rate due to alcohol, the drug becomes the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States at 88,000 deaths annually. Alcohol consumption is a known risk factor for suicide, homicide, injury, and other drug use which further exacerbates its overall burden.

As the graph above shows, alcohol-related deaths are at a 35-year high. They increased by 47% between 2000 and 2015. Women have experienced the most dramatic proportional increases in death rates (75%). White alcohol-related deaths have increased by 130% since 1999, compared to a 27% increase in the rate of Hispanic deaths and a 12% decrease in the rate of African-American deaths.

The report calls for a “National Resilience Plan,” suggesting policy-level remedies. The most effective alcohol-related policies include:

- Increasing excise (based on volume sold) and sales taxes (percent of retail price)

- Limiting the number of retailers in any given area and the days and hours when alcohol can be sold

- Holding the owner or server liable for injuries or deaths related to illegal sale of alcohol

- Raising the legal drinking age

—Madeline Bishop, PHP Fellow

Graph from “Pain in the Nation: The Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Crises and the Need for a National Resilience Strategy,” Trust for America’s Health and Well Being Trust Issue Report.