Good App Hunting

Public health and medicine are in a moment of digital euphoria. We have convinced ourselves that mhealth (mobile phone) technologies will improve the health of millions.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Good App Hunting

Public health and medicine are in a moment of digital euphoria. We have convinced ourselves that mhealth (mobile phone) technologies will improve the health of millions. After all, there are 6 billion smartphones out there and more than 300,000 stand-alone health apps on the market ready to be uploaded. Suddenly, the promises of behavior change to improve the care of highly prevalent conditions (obesity, diabetes, anxiety, insomnia) are scalable. But as behavioral health facilitators, will phone apps work and how will we know if they do?

Health apps monitor, measure, and manage. (Let’s set aside for another time the apps that connect wearable devices to the electronic medical records that Apple and Google and others are creating). The first generation of apps were about self-monitoring. These “do it yourself” kinds of apps had users record and consider their own data—food ingested, mood, glucose levels—and offered users opportunities to modify their behavior. Next came measuring, quantifying apps, which soon became sensor-based, including recordings of heart rate, steps walked, sleep stages, food labels. Such sensors limited manual input and offered novel “health” markers to monitor. We have recently entered the era of the “prescribable” app. An app for the treatment of managing depression at home, at your fingertips, at any time, some even recommended by health providers.

The most commonly-trialed apps have been designed to address conditions with the largest global health burden: diabetes, mental health, and obesity. But of all the health apps on the market, only a few dozen have ever been tested using randomized trials. And these trials, as with most new treatments, involved few participants, assessed for short periods of time, and in general were poorly designed, performed, and analyzed. This should not be a surprise; funding sources for app development and testing are rare, and a full-scale clinical trial can be long and expensive, and risks a negative result. Waiting for the demonstration of positive benefits is not yet the modus operandi of this new field.

In the digital world, faulty anecdotes of health success can go viral. We need a means for efficacy assessment and a reliable source of quality information, a Consumer Reports for health-related apps, and a recognized national organization that can evaluate and decide which are safe and which are worthy. Even a modestly potent app, if available to millions of users, could have an enormous impact on the public’s health. But the search for app evidence is time-consuming and challenging, and in the digital age, none of us has enough time.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

LONG-TERM (NO) CARE

The more than 15,000 Medicaid and/or Medicare-certified nursing homes provide care to nearly a million and a half residents. The Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services inspects these nursing homes and rates their quality using a 5-star system. These authors confirm two tiers of nursing homes, the “lower tier,” disproportionately located in counties with lower incomes. For-profit, chain-affiliated, larger nursing homes received lower star ratings. Nursing homes located in socioeconomically disadvantaged counties may lack the resources to improve staffing or hire qualified personnel to meet the needs of the residents, both critical to providing high-quality care. These findings suggest the need for policies that support additional resources for nursing homes in underserved and less populated areas where the great majority of residents rely on Medicaid as the primary source of payment.

UPWARD AND HEALTHWARD

In this study of 147,000 low-income persons aged 25-35, these authors consider the relationship between economic opportunity at the county level and self-reported health. They define economic opportunity, or the prospect of “upward mobility,” as the average income that individuals born to the poorest quartile of parents were able to attain as adults. They report that higher economic opportunity is associated with improved self-reported overall health, physical health, and mental health, and reduced likelihood of smoking and undertaking risky sexual and drug use practices. Without economic opportunity, health and the motivation for self-care may be undermined.

MAKING STRIDES TOWARDS ZERO

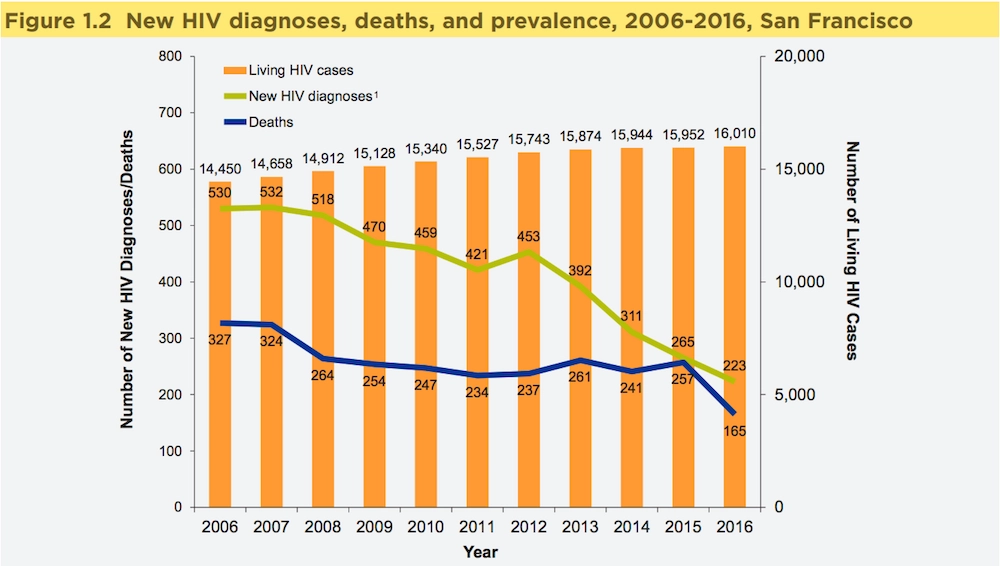

San Francisco has made steady progress toward fulfilling its goals of achieving zero HIV deaths, zero new infections, and zero stigma by 2020. These goals are aligned with the UNAIDS Fast-Track strategy for reaching the three zeros globally.

In its annual report for 2016, the San Francisco Department of Public Health’s HIV Epidemiology section summed up data on new and existing HIV infections and HIV-related deaths in the city. According to the figure above, the number of new HIV diagnoses decreased steadily between 2007 and 2012, when there was a brief uptick in new cases. By 2013, incidence resumed its downward trajectory. The number of people living with HIV went up gradually each year due to life-saving treatment. HIV-related deaths held fairly steady between 2008 and 2015 before dropping dramatically in 2016.

Getting to Zero SF specifically aims to reduce HIV infections and deaths in San Francisco by 90%. The campaign’s strategy includes improving access to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), expanding the city’s hubs for RAPID (Rapid Antiretroviral Therapy Program for HIV Diagnoses) participation, and encouraging action to keep patients in care and improve their treatment adherence.

Despite the city’s progress, vulnerable groups in San Francisco continue to be heavily affected by HIV. For example, only 31% of the homeless population reached undetectable blood levels of HIV in 2016. In order to reach zero, agencies in San Francisco will have to tackle its housing crisis as a part of its HIV strategy. —Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Graph: HIV Epidemiology Annual Report 2016, San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health Division.