The Mental Toll of Misdiagnosis

Misdiagnosis can lead to long-term emotional distress, feelings of worthlessness, and diminished trust in the broader health care system.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Patients with autoimmune diseases and other chronic conditions often endure a prolonged, frustrating diagnostic journey. Many chronic illnesses are characterized by a combination of vague, non-specific symptoms that can be easily missed—or dismissed—by clinicians.

For example, multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease that damages nerves, is sometimes misdiagnosed as migraine headaches or depression due to overlapping symptoms. But when patients are told their suffering is caused by migraines or mental health conditions, they may delay or forgo seeking further care, even as more serious MS symptoms emerge. When patients feel dismissed or gaslit by their doctors, the harm goes beyond delayed diagnosis and inadequate treatment. Misdiagnosis can also take a serious toll on mental health and erode trust in the health care system.

In a recent study, Melanie Sloan and colleagues interviewed and surveyed over 3,400 patients with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases, comparing three groups: 1) people misdiagnosed with a psychosomatic and/or psychiatric condition; 2) people misdiagnosed with a physical disease; and 3) people who were not misdiagnosed.

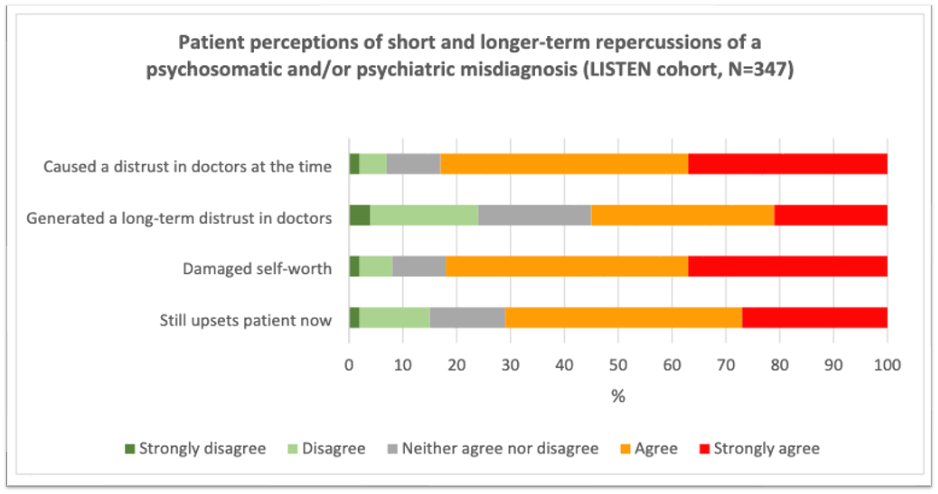

Those with psychosomatic or psychiatric misdiagnoses experienced the worst outcomes. More than 80% said that the experience severely damaged their self-worth, and 72% reported lingering emotional distress years later. Others described how their misdiagnosis contributed to or worsened their depression and anxiety.

On average, those with psychosomatic or psychiatric misdiagnoses were less satisfied with their care and reported lower trust in both clinicians and the broader health system than those misdiagnosed with a physical disease. They were also more likely to under-report symptoms and avoid seeking care altogether—behaviors that further complicate accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Autoimmune diseases affect approximately one in twelve Americans, and rates are on the rise, so the physical and mental harms of misdiagnosis compound an already mounting public health challenge. While diagnosis is an imperfect science and not all misdiagnoses result from error or negligence, the study authors emphasize that when misdiagnosis does occur, clinicians should acknowledge the outcome and its impact on the patient. Doing so is a critical step towards rebuilding trust and restoring patient well-being.