The Smoking Gap

Four in ten Americans smoked cigarettes in 1965; now, only 15% smoke. That’s a huge public health feat, but it is not the end of the story.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

The Smoking Gap

Four in ten American adults smoked cigarettes in 1965; only 15% smoke today. That’s an impressive public health success, but it should not be the end of the story. There remain 40 million smokers in the United States who will suffer cancer and cardiovascular consequences from the dozens of harmful chemicals in tobacco products for decades to come, at a cost of $300 billion per year.

Fifty years ago, smoking prevalence for all education groups was clustered at that 40-45% mark. Five decades later, 6.5% of college-educated individuals continue to smoke, while the prevalence is more than triple that among those with a high school education or less (23.1%). These smokers tend to be disadvantaged socially and economically, and bear the majority of morbidity and premature mortality. Education seems to matter.

So we have lowered smoking overall, and in the process we have created a smoking gap, between those who are well educated and those who are less educated, between those with higher and lower incomes.

And the smoking gap is not restricted only to socioeconomic status. Geography is also at play. “Tobacco Nation,” a swath across the American southeast where 700 million pounds of tobacco are harvested annually and rates of smoking remain higher than elsewhere, suggests that policy, culture, and the persistent influence of the tobacco industry in this region has effects. At the county level, rural dwellers have higher rates of cigarette use, which may or may not result from intentional industry targeting. Workplace smoking bans will not lead to cessation among people who work outdoors or who are unemployed, two conditions notable in rural areas.

Other studies have documented the high tobacco retailer density in neighborhoods with larger proportions of African Americans, the ethnic group with the highest smoking prevalence. This causal relationship may work in both directions: more retailers sell tobacco because there are more tobacco users, and current smokers smoke more tobacco because there is heightened exposure to these tobacco retail environments.

What do we learn from the smoking gap?

First, this is part of a pattern which we observe in health. Efforts to fix the immediate health behavior (in this case smoking) fall short when we do not deal with the underlying problem—often one of social or economic disadvantage. This has been well documented in medical sociology and is called the fundamental cause hypothesis.

Second, innovative interventions, implemented at the national, state, community, and local levels and focused on disadvantaged groups, provide the best chance to lower the smoking rate further. But it will take a series of such actions, based on evidence: setting minimum pricing policies across states; strategic partnerships with the 2-1-1 phone system whose callers are disproportionally low income, unemployed, and/or uninsured; reducing sales of untaxed or low-tax cigarettes; social branding interventions that target young adults and look to prevent smoking initiation; supporting the ban on smoking in public housing; expanding care access to smoking-cessation counseling and medication benefits via Medicaid expansion. Electronic cigarettes represent another avenue to improve the health of smokers, but there is little evidence that e-cigarette use leads to smoking cessation. There are certainly other approaches and policies worthy of consideration beyond this list.

Reducing the smoking rate to below 15% will be particularly challenging. But we know the best public health approach will need both to tackle the foundational problems that shape our health and to target the populations at greatest risk.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

THE LEGACY OF TUSKEGEE

Nearly half of all Americans living with HIV are Black and rates of new cases are eight times higher in Blacks than Whites. This study interviewed HIV-infected Black veterans, most of whom were receiving treatment at the Veterans Health Administration, the largest provider of HIV care in the United States. Many participants believed that HIV was a disease created by the government to control poor and minority populations and that pharmaceutical companies withheld the cure for HIV/AIDS. Others suspected that the medication they’d been prescribed sped the progress of HIV infection to AIDS; therefore, they deceived their healthcare providers regarding their medication adherence. Conspiracy theories about HIV still abound and may contribute to poor treatment outcomes among Black veterans and perhaps other veterans as well.

GETTING-BACK-TO-HOME COOKING

Social service agencies are increasingly collaborating with healthcare institutions to improve the health of communities. These researchers describe a collaboration between a hospital and an agency on aging to offer specialized meals (e.g., vegetarian, pureed) to patients after hospital discharge. The program delivered meals weekly to the doorsteps of 622 high-risk Medicare patients during their transition from hospital to home or to an alternative setting, such as long-term care. Over a 24-month evaluation period, the Simply Delivered Meals (SDM) program, added to standard supervised community care transition planning, led to a 38% decrease in hospital readmission rates, compared to the pre-SDM period. Home-delivered meals to patients that attend to dietary restrictions can help frail, low-income persons remain out of the hospital.

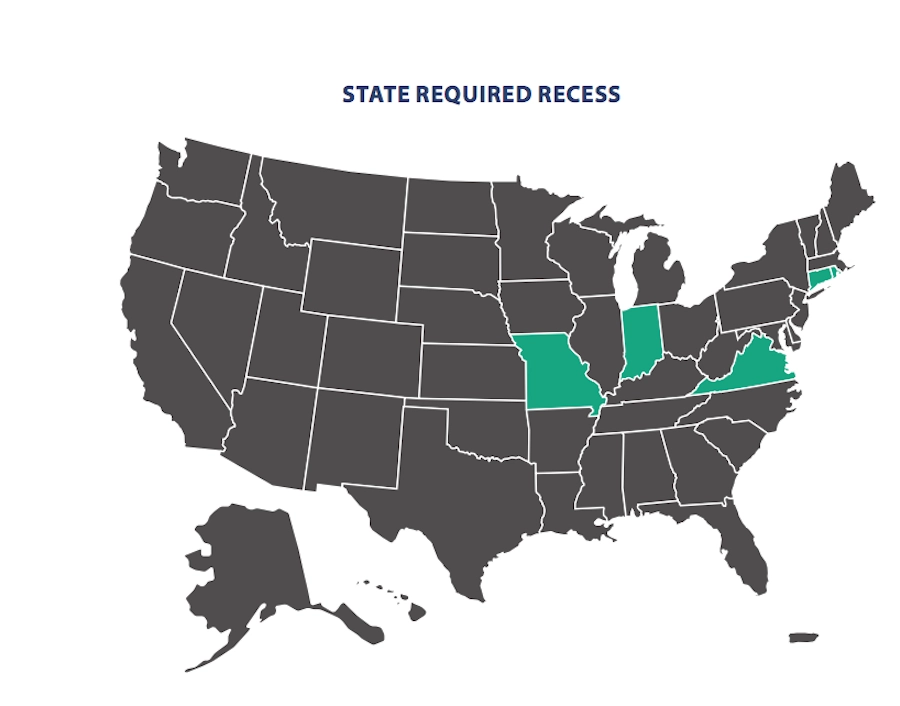

RECESS IN PIECES ACROSS THE US

Obesity rates among US children have tripled in the past three decades. This places children at higher risk for poor health outcomes, such as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease. They are also more likely to be overweight as adults. While causes can vary between individuals, common solutions include physical activity, healthier food choices, and participation in health-oriented community education events. In 2017, the Council of State Governments published a research brief summarizing physical activity legislation across the United States. School recess is one attractive option for increasing physical activity and it also benefits children’s emotional, social, and mental health. Physical exercise can increase attention span and improve academic performance.

Only five states, shown in green on the map, have legislation mandating recess in elementary schools: Connecticut, Indiana, Missouri, Rhode Island, and Virginia. Each state passed legislation aimed at elementary schools, mandating a recess period (or, in the case of Indiana, physical activity, which may “include the use of recess”). Connecticut, Missouri, and Rhode Island have a minimum recess requirement of 20 minutes, whereas Virginia and Indiana do not mention time in their policies. Eight other states have “general activity” requirements, mandating daily or weekly physical activity, expanding into physical education, field trips, exercise programs, etc. These are: Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Texas.

All other states supplement mandatory recess with alternative policies, primarily physical education, and vary in their degree of requirement. Massachusetts has mandatory physical education for grades K-12, but no recess requirements. That may change, as Rep. Marjorie Decker introduced a bill in 2017 to provide grades K-5 with 20 minutes of recess.

Bills emphasizing academic achievement, such as the No Child Left Behind Act, encourage increasing class time, often taking time away from recess. Multiple organizations, including the Center for Disease Control, recommend that physical activity and recess should be mandatory. —Erin Polka, PHP Fellow

Map: The Council of State Governments, State Policies on Physical Activity in Schools, Matt Shafer, CSG graduate fellow, and Elizabeth Whitehouse, CSG director of education and workforce.