The Downside of Drinking

In the midst of a lethal opioid epidemic, alcohol kills more Americans than fentanyl, heroin, and prescription pills combined.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

The Downside of Drinking

In the midst of a lethal opioid epidemic, alcohol kills more Americans than fentanyl, heroin, and prescription pills combined. During the past decade, in parallel to the increase in opioid use, deaths by alcohol have increased 35 percent. Although men still make up three-quarters of alcohol deaths, young women have had the greatest rise in deaths through accidents, suicide, cancer, and cirrhosis. Around forever, culturally normalized, this ancient substance seems to be newly hazardous. What’s happening?

We have some ideas. First, the alcohol industry continues to be powerful and savvy. Beverage companies spend $2 billion a year advertising, 90% on television, mostly on beer. Industry advertising never says that alcohol is not addictive; rather the message is “use responsibly,” which implies that alcohol’s use—unlike the use of drugs—is controllable.

Second, although we don’t have a greater proportion of Americans drinking (it’s remained steady at about 2 in 3 people over the past 70 years), we are drinking more, and more easily. We can now buy liquor in movie theaters and in grocery stores and on Sundays. Last year, Congress reduced alcohol excise taxes, bringing down prices; state legislatures won’t raise taxes and risk losing revenue.

Third, during this decade of economic expansion, many Americans have more income. In contrast to the stereotype, affluent people are more likely to drink than low-income people. At the same time, as the poor get poorer, the devastating health effects of heavy drinking are compounded by higher cigarette and other substance use and greater mental health problems.

Fourth, binge-drinking is now a rite of passage in college. With women a growing percentage of collegiate heavy drinkers, and with alcohol-makers targeting women with sweeter and fizzier products, health risks accumulate as women generally experience greater effects at lower doses than men.

Fifth, we’ve become complacent about driving under the influence because seatbelts and safer cars have lowered alcohol-related fatalities. Yet paradoxically, alcohol-related traffic accidents are on the rise (perhaps worsened by growing marijuana co-use). Our drunk-driving blood alcohol threshold remains steady at .08 despite the National Transportation Safety Board’s recommendation to lower it to .05, the standard in many other countries with lower rates of traffic fatalities.

We used to think that drinking a little bit had cardio-protective effects. But the science has advanced to show that that is not the case. No level of alcohol consumption improves health. Simply put, alcohol is an eminently preventable cause of social harm and premature death. Consuming less alcohol in total or on a per-occasion basis would probably improve the health of most of us. That’s a credible and reasonable public health goal.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

GETTING HURT WHILE DOING GOOD

One million emergency medical service (EMS) personnel in the United States respond to more than 30 million calls for assistance annually. The EMS profession is one of the most dangerous, with fatality rates and nonfatal injury rates for personnel higher than for other American workers. These researchers examined 1,630 violence-related occupational injury cases reported by EMS workers to the Bureau of Labor statistics. They found that one-third of injuries are unintentional and occur when the EMS is trying to restrain, subdue, or move a patient. Another third are intentional and violent, perpetrated by patients. Many incidents result in fractures and muscular injuries. Women may be at higher risk. EMS agencies must continue to train employees in self-defense, improved situational awareness, and communication.

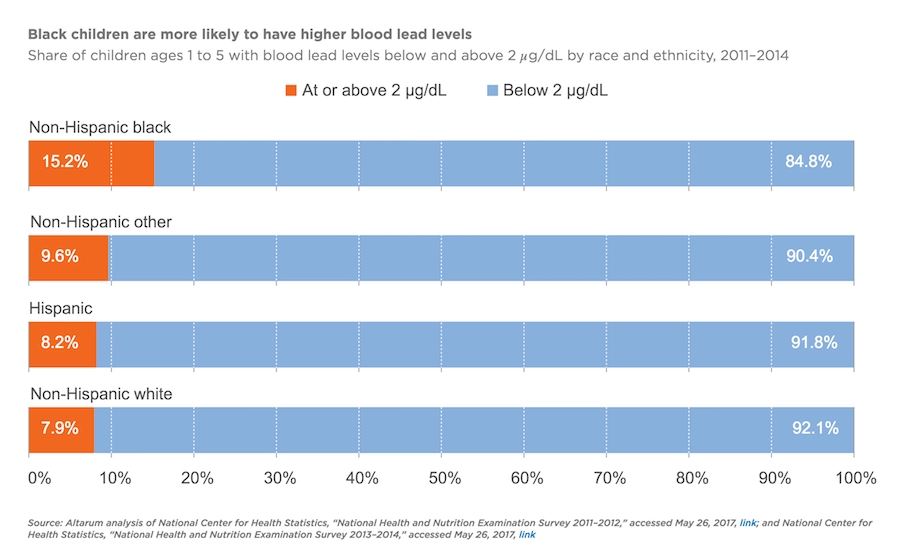

RACIAL GAPS IN CHILDREN’S LEAD LEVELS

The Flint, Michigan water crisis made headlines for months, but it is not the only city in the United States with lead-contaminated water. A USA Today Network investigation found nearly 2,000 water systems across the country have excessive lead levels. Children of color are particularly vulnerable to lead exposure from the water they drink, especially in places where they spend a lot of time: their homes, schools, day care centers, and playgrounds.

In a report released by Child Trends, Vanessa Sacks and Susan Balding call attention to lead poisoning among children of color, especially non-Hispanic Black children. As shown in the graph, almost twice as many non-Hispanic Black children have lead levels at or above 2 micrograms per deciliter compared to non-Hispanic White children.

High blood levels of lead in children can be fatal, but low blood levels can be harmful as well. Low levels can affect cognitive development and are associated with reduced IQ, reduced attention span, and an increase in antisocial conduct. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are unequivocal. No amount of lead in the blood is considered safe for children.

An estimated 15 to 22 million people drink and bathe in water that runs through lead pipes.

Children may also be exposed to lead through paint. According to the American Healthy Homes Survey, 52% of homes built before 1978 contain lead-based paint. Data from this survey also indicate that the older the home, the more likely it is to contain lead-based paint. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that 3.6 million homes with young children living in them have lead paint. And many communities are exposed to high levels of lead in the air and soil.

So, what are some possible solutions for reducing lead exposure? When it comes to lead-contaminated water, removing lead pipes is the key. Removing or covering lead paint using safe techniques will help as well. —Chrissy Packtor, PHP Fellow

Graph from Child Trends, “The United States can and should eliminate childhood lead exposure,” by Vanessa Sacks, Susan Balding, February 2, 2018