Veterans and Health Misconceptions

Soldiers protect us and keep us safe, and their health is the public’s health, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Veterans and Health Misconceptions

There are 200,000 new veterans each year, adding to the 20 million Americans who have served in the military. Nearly five decades since our military went all-volunteer, and after almost two decades of constant war, we continue to misunderstand the military. Novelists and moviemakers depict veterans who are disconnected and marginalized. That is largely not so. The military is solidly middle class and, in many ways, a select group. High physical and educational standards—a high school degree required—means that 71% of young adults would fail to qualify if they tried to enlist. The military is also an ever more diverse group. Women now make up one in six enlisted, and both sexes are more ethnically diverse than the civilian population. Veterans are more likely to vote, volunteer, give to charity, and attend town meetings than non-veterans. Female and black veterans experience a wage premium (2% and 7% respectively) over non-veterans.

The military, and veterans, therefore increasingly represent a rapidly diversifying middle of the country. But the health of the active military and veterans highlights the challenges our soldiers face. Since the first Gulf War in 1990, veterans have had worse mortality than the general population, due perhaps to multiple deployments and survival from injuries that would have killed soldiers in the past.

Aside from mortality, mental health problems are a particular concern. More soldiers kill themselves than are killed on our battlefields—20 a day, which is 50% higher than the civilian rate. The majority of these suicides are over 55 years old, although rates among younger veterans have been rising.

Beyond suicide, a key mental health concern among veterans is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD, itself disruptive, foreshadows increased risks of physical health problems, substance use/misuse, homelessness and violence. Less studied, but equally important, are high rates of depression and anxiety in this group. Rates of chronic pain and physical disability rates are also unfortunately high. All of these make the Veterans Health Administration’s unique expertise in mental health care provision and rehabilitation services all the more crucial.

Despite these health challenges, only 30% of veterans use Veterans Health Administration facilities. Yet our current administration is reducing this access further in a move toward privatization of veterans’ health. This does veterans a disservice, shortchanging one of the fundamental social contracts we make with each other: soldiers protect us and keep us safe, and we promise to look after them when they finish their service. Their health is the public’s health.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

INSTALLING SAFETY

Thousands of Americans die each year in house fires. Having a smoke alarm in the house cuts the risk of injury and death by more than half. Unfortunately, only half of homes have a functioning smoke detector at the time of a fire. These authors performed a cost-benefit analysis of a community-based smoke alarm installation program in Dallas in high-risk neighborhoods, defined as low-income with a high rate of past fires. They estimated a $3.21 return on investment for every dollar spent on the program. Savings in medical care, lost productivity, and fatalities over the five years post-installation suggest the good value of door-to-door distribution of smoke alarms.

RESURGENCE OF BLACK LUNG IN CENTRAL APPALACHIA

Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis or “black lung” develops when dust particles are inhaled while working in coal mines. These particles can cause both inflammation and scarring in the lungs.

In 1969, the Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program (CWHSP) was created with the intention of identifying and stopping the progression of black lung in coal miners. The same bill that created the CWHSP also required companies to limit coal miners’ exposure to dust.

Despite these programs and regulations, central Appalachian coal miners are experiencing a resurgence of black lung. A recent study from researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health sought to update the prevalence estimates for black lung in the United States.

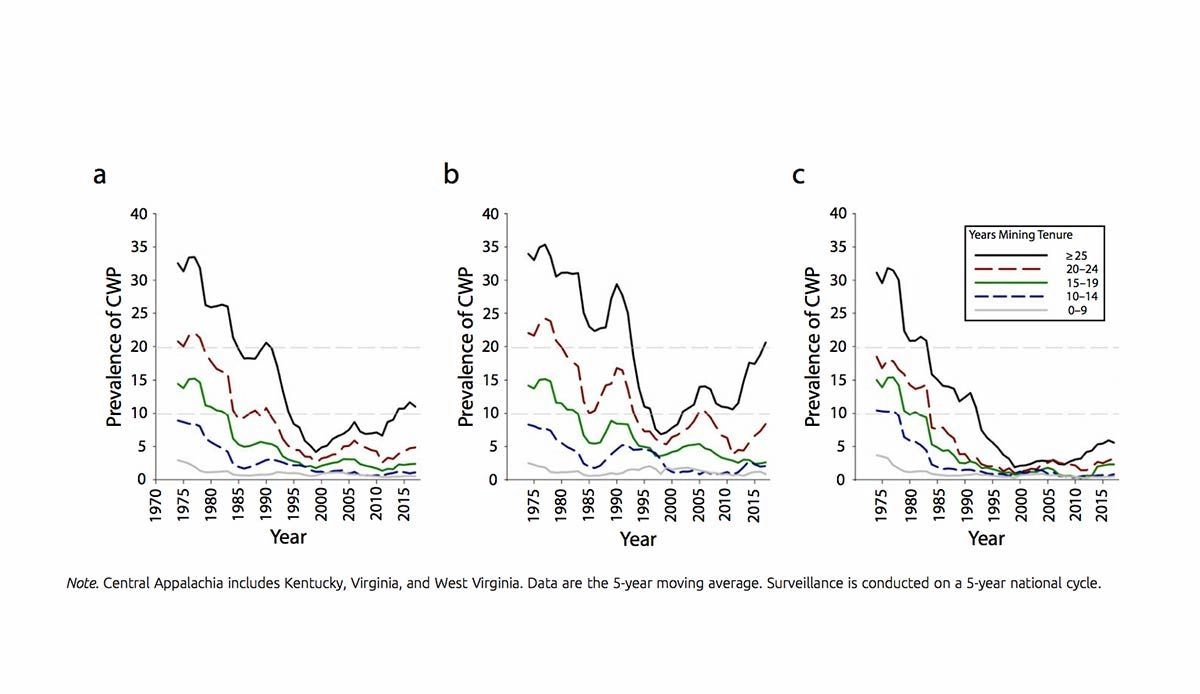

Graph A above shows the prevalence of black lung throughout the United States. Graph B shows the prevalence of black lung in central Appalachia, and graph C shows the prevalence of black lung in the United States excluding central Appalachia. In this study, central Appalachia included West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia.

Throughout the United States, over 10% of coal miners with 25 years or more of tenure have black lung; in central Appalachia, over 20% of miners with the same experience do. The overall prevalence of black lung in long-tenured coal miners is at its highest level in 25 years.—Chrissy Packtor

Graph via “Continued Increase in Prevalence of Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis in the United States, 1970–2017,” David J. Blackley, Cara N. Halldin, A. Scott Laney, American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 9 (September 1, 2018): pp. 1220-1222.