Crowdsourcing the Opioid Epidemic

In 2015, Boston established a Mobile Sharps Collection Team to respond to discarded needle pick-up requests throughout the city. Data from discarded needle locations could provide an opportunity to address the underlying epidemic.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

Boston’s streets are full of the evidence of the ongoing opioid epidemic, which is killing Americans at an alarming rate. Drug-use-associated litter is a problem that poses minor public health risks but stokes significant community anxieties. While many cities have established needle exchanges or safer needle disposal programs, these services are underutilized because of the stigma associated with substance use disorders, and some have recently closed, facing political and financial pressures.

In 2015, Boston established a Mobile Sharps Collection Team to respond to discarded needle pick-up requests throughout the city. These crowdsourced requests leverage the existing non-emergency 311 infrastructure by allowing Boston residents to request a needle pick-up through a website, Twitter or, most commonly, the Bos:311 mobile app. Notably, Boston has made the data from this program publicly available.

These crowdsourced and publicly available data shine a bright light on the role of citizen scientists in building healthy communities.

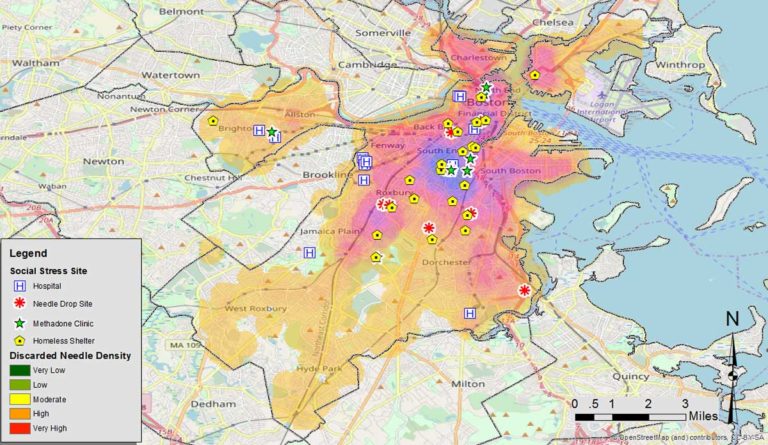

As Boston-based clinicians and researchers caring for patients with substance use disorders and interested in publicly available data, we wondered: could the data from discarded needles provide an opportunity to address the underlying epidemic? More specifically, could examining temporal and spatial trends in discarded needles throughout the city help us develop community responses to the opioid-use and overdose epidemics? Our initial findings were published last month in the American Journal of Public Health. We highlight the rising number of reported needles in Boston, up from 600 needle pick-up requests in 2015 to well over 2,000 in 2017. We identify discarded needle hot spots clustered in the South End and Roxbury neighborhoods, with several outlying hotspots in the North End, Allston-Brighton and the South Boston-Dorchester border. Using additional geospatial methods like buffering analysis, where we calculate discarded needles within a set distance from points of interest, we also found an association between sites of high social stress (hospitals, homeless shelters, safe needle disposal sites, methadone clinics) and areas with a high density of publicly discarded needles.

These crowdsourced and publicly available data shine a bright light on the role of citizen scientists in building healthy communities. By reporting discarded needles, Boston community members call attention to the immediate public health risks of needlestick injuries, while the resulting data can be used to target services for individuals with substance use disorders more effectively. People who inject drugs face significant stigma. They also lack safe places to use and reliable access to harm reduction services including needle exchange and naloxone to reverse overdose.

There are at least two hundred municipal 311 programs in the United States and a number of international cities have followed. The crowd-sourced data generated by these programs provide a precise accounting of public concerns; however, few cities are reporting their data publicly. So far, only Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco are collecting discarded needle data. We hope that our work highlights the value in public reporting of drug-related litter. By uniting community members, researchers, and public health advocates we hope to catalyze an increase in targeted harm reduction services including syringe exchange, overdose prevention sites, and access to medications to treat opioid addiction.

Map created in ArcGIS by John F. Pearson, MD. Sources: MassGIS, OpenStreetMap.org, BOS:311