What Kills Our Kids?

One of the greatest triumphs in health over the past century has been the dramatic decrease in childhood mortality.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

What Kills Our Kids?

One of the greatest triumphs in health over the past century has been the dramatic decrease in childhood mortality. And yet, children still die, and that suggests that we should be looking carefully at what kills our children, and asking what we can do about it.

In 2016 there were, in the United States, about 38,000 deaths of children under the age of 19. Roughly half of deaths occur in early childhood due to genetic conditions, chromosomal abnormalities, and other perinatal conditions, many of which we do not know how to treat. But the majority of the other half we should be able to do something about. The vast majority of these deaths are due to injury, a combination of car accidents, and gun-related deaths, suffocation in early childhood, drowning, drug overdose.

Let us look at the two largest causes of these injury deaths: motor vehicle deaths (nearly 4,000) and gun-related deaths (nearly 3,000). Nearly all of these deaths are in theory preventable.

We are step by step tackling motor vehicle deaths. The Vision Zero initiative, passed by the Swedish parliament 20 years ago, aims to reduce traffic fatalities to zero by 2020. The effort—which includes monitoring traffic flow and vehicle technology solutions such as novel automatic braking systems—has reduced fatalities dramatically not only for those in cars, but also for pedestrians whose fatality rate has decreased by more than 50%. A number of US cities, including New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco, have adopted the Vision Zero approach and are also showing success.

The success of the Vision Zero initiative is predicated on a simple idea: “We are human and make mistakes” and as such we need to design safer roads and cars—in other words the world around us—to keep us safe.

We have done very little on the other major injury cause of death—guns. But just like motor vehicle accidents, child death from guns will not improve unless we reduce the availability of guns and make them safer. Multiple low-tech firearm features can prevent accidental gun discharges, including heavier trigger pulls and grip safeties. No federal agency oversees how guns are designed or built, even though federal safety regulations are standard for other consumer products like cars.

The National Cancer Institute spends about $200M annually on childhood cancer, which kills about 2,000 children a year. By contrast, our spending on preventing injury, including gun injury, is abysmally low. System design takes human fallibility into account and can protect children. Let’s spend some of our research dollars there.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

To our readers: After this issue, we are taking our summer publishing break. The Public’s Health will resume on Wednesday, August 22.

PHARMACISTS: DO NO HARM, BUT MORE GOOD

As overdose numbers continue to rise, pharmacists can take a more active role in reducing patient overdose risk by providing naloxone to the friends and family of those at risk. Some pharmacists continue to have misconceptions about potential legal risks of dispensing naloxone not prescribed in a traditional physician-patient relationship. These authors outline the recent legal and regulatory innovations that encourage the prescription and dispensing of naloxone. Thirty-six states provide special protection from civil liability for pharmacists dispensing naloxone, and 32 states provide protection from potential criminal action and pharmacy board disciplinary action.

CAN’T GET NO SATISFACTION

Feeling satisfied with life is associated with better physical and mental health and lower health care costs. No wonder that researchers have looked for interventions to enhance our sense of well-being. This randomized trial called Fun for Wellness offered 24-hour access to 152 online “challenges” that included games and exercises to enhance skills thought to promote well-being (e.g. how to set a goal, how to collect positive emotions). There was no measurable positive effect of the intervention. As with any internet-based intervention, it was hard to keep people engaged, even with the prospect of arriving at “the best your life can be.”

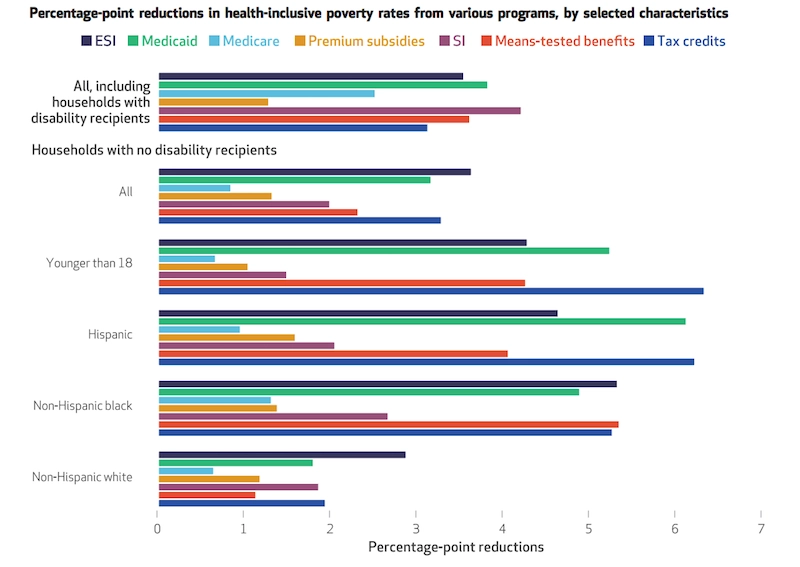

HEALTH INSURANCE REDUCES POVERTY

A recent Health Affairs article pioneers a new way to gauge the impact of health insurance. Dahlia Remler, Sanders Korenman, and Rosemary Hyson developed a measure of poverty which differs from the Census Bureau’s measure of poverty by taking health into account. Through this measure, they demonstrated that public health insurance programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and premium subsidies on an exchange, reduced poverty rates by 4.6 percentage points. Children younger than 18 years of age benefited particularly from Medicaid and CHIP, with a 5.3% reduction in poverty. But the strongest overall effect was a 17.1% reduction in poverty experienced by people on Medicaid. —Qing Wai Wong, PHP Fellow

Health Affairs Vol. 36, No. 10, 1828–1837. “Estimating The Effects Of Health Insurance And Other Social Programs On Poverty Under The Affordable Care Act,” Dahlia K. Remler, Sanders D. Korenman, and Rosemary T. Hyson. Published: October 2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0331