What Data Do We Need for Health?

Our charge should be to collect data that tell us how our time spent affects our health, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

What Data Do We Need for Health?

We spend, as the reader of this column will already know, an inordinate amount of money on our healthcare. Much of our recent spending goes to data acquisition, to medical monitoring, and to assessment of how our health systems function.

Are there other places where money devoted to gathering health data might be better spent?

Our health is a product of the world around us. This is perhaps most easily understood by thinking about how much time we spend in the various places where we live, work, and gather.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics offer a picture of what we are doing and where we are doing it. Out of 8,736 hours in a year, we spend more than half, or about 4,566 at home. We spend 1,893 hours in our workplaces or 1,198 at school. We spend 93 hours in places of worship. Far down the list, at 15 hours a year, are interactions with the healthcare delivery system.

That picture is enough to make two things clear.

First, insofar as health is generated by where and how we live our lives, health is what happens between visits to doctors and hospitals. We are simply not in contact that much with our doctors and the healthcare system, and so it must be something about the many other hours in our life that determines our health.

Second, because healthcare is really a very small part of our life, it should not take up too much of our health improvement time or attention. Ultimately, medical care is a means to the end of living a full and satisfying life.

So, with this in mind, we revisit the question we started with: what data do we need to generate better health? We believe that when we understand where health is generated, it becomes self-evident that we need data about how all that other “non-medical” time produces health.

As we rush to think about apps and systems that collect data, we believe our charge should be to collect data that tell us how our home life, our time spent at work, and our time spent in schools and in places of worship affects our health. Innovation in this area of data collection can break new ground and undoubtedly make a lot of money for those who pioneer it.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

FOR PROFIT BUT ALSO FOR GOOD?

Social impact bonds (SIBs), a new way to fund public health services, allow private entrepreneurs—equity funds, individuals—to manage and potentially earn a profit by organizing social programs that state and local governments may not run efficiently. For example, investors could develop a system to reduce prison recidivism and share the public savings (reductions in prison costs) with the sponsoring government. While SIBs, dozens of which are now active in the US, may appear as low-risk collaborations for governments interested in pursuing underfunded programs such as affordable housing, these researchers point out that SIBs are typically aimed at highly racialized issues such as prison recidivism, teen pregnancy, and homelessness. SIBs may not address the root causes of these difficult social problems and might undermine some existing social services.

NURSE PRACTITIONERS AND COUNTRY LIVING

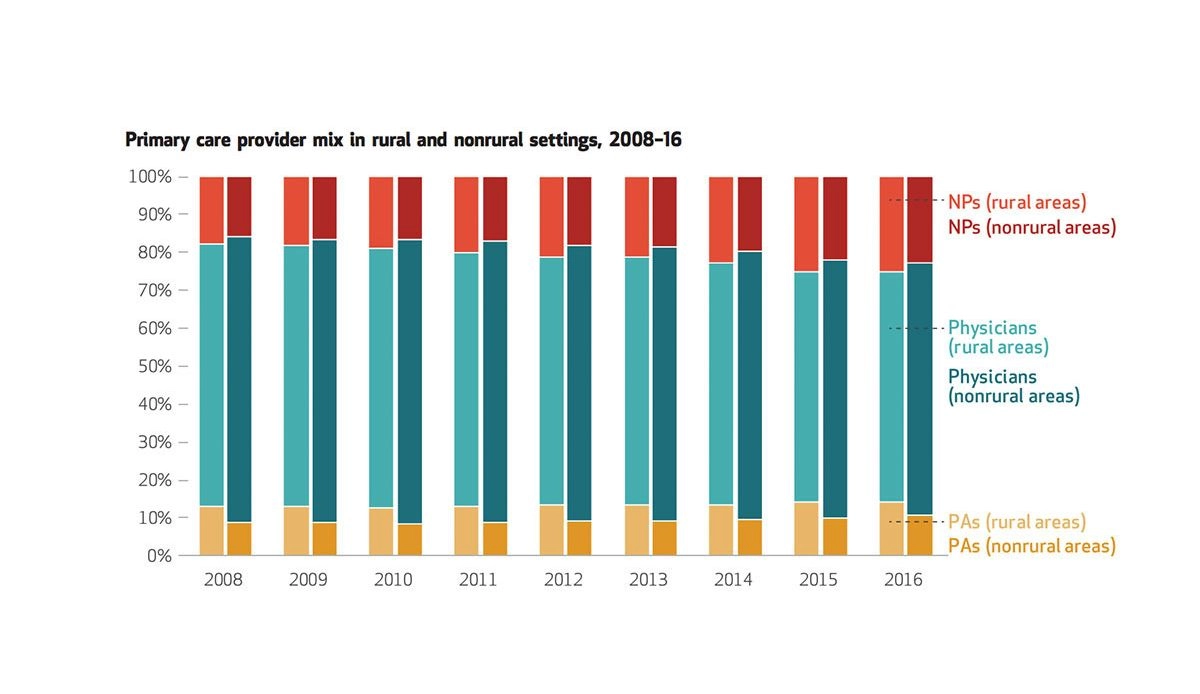

The association of American Medical Colleges predicts a shortage of 120,000 physicians overall by the year 2030, estimating a shortfall of up to 49,300 primary care physicians in the United States. The role of nurse practitioners in the primary care setting may increase, however, as their numbers are expected to rise over the next decade. In light of these predictions, Barnes and colleagues studied the trends in nurse practitioners who practiced in rural and nonrural primary care settings between 2008 and 2016.

The researchers analyzed a dataset featuring characteristics of doctors’ offices, focusing on the number of nurse practitioners, physicians, and physician assistants. As the figure above depicts, they found that the proportion of nurse practitioners as a percentage of total primary care providers grew from 17.6% to 25.2% in rural areas over the observed years. Nonrural areas also saw a growth in the presence of nurse practitioners, from 15.9% to 23%. Although physicians made up the largest proportion of providers in both rural and nonrural settings, their percentage dwindled. Further, the authors found that a greater proportion of rural practices featured nurse practitioners among their provider teams compared to nonrural practices.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality identifies high-functioning primary care teams as those including multidisciplinary involvement. Considering their findings, and other data documenting the high satisfaction with care from nurse practitioners and their lower practice costs compared to physicians, Barnes and the other researchers suggest that policymakers invest more in nurse practitioner education.—Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Feature image from “Rural And Nonrural Primary Care Physician Practices Increasingly Rely On Nurse Practitioners,” Hilary Barnes, Michael R. Richards, Matthew D. McHugh, and Grant Martsolf, Health Affairs 37, No. 6 (2018): 908–914.