We Cannot Have it All

Public health must not allow lopsided interventions and approaches to happen, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

We Cannot Have it All

Imagine for a minute that you are the health commissioner responsible for a town of 100,000 people. The mayor calls you into her office and reminds you that one of her campaign promises was to improve the flu vaccination rate in the town. The previous season, 45% of the town’s residents received the vaccine. This season she wants the vaccination rate to hit 65%. That all sounds reasonable, and with your team you develop a strategy that communicates primarily through doctors’ offices the importance of flu vaccinations. You develop written material and some videos and you make sure that all patients see them prominently displayed. The strategy works. At the end of this year’s flu season, you have vaccinated 65% of everyone in town.

An enterprising analyst in the health department then looks at the data a bit more carefully. She notes that the town really is divided into two groups. Half the town, in its north end, is rich and there the flu vaccination rate was already 60% when you started. It rose to 90% at the end of the campaign. The southern, poorer half of town had a vaccination rate of 30% when you started; it rose to 40% by the end of the campaign. Therefore, you increased the vaccination rate by 30% among the rich, and by 10% among the poor, many of whom do not get to doctors’ offices and as such did not benefit as much from your campaign. Your rich-poor gap in vaccination was 30% when you started; it was 50% when you finished.

So, was your campaign a success?

At the level of what the mayor promised in her campaign—that more residents would be vaccinated—it was. In fact, you increased rates overall by 20%, which is impressive. And you can point to the fact that the rates of vaccination improved among everyone. Yes, they increased less in the poor parts of town, but they did increase.

But the health gaps in town between the rich and the poor residents also increased, and they did so substantially. This is an illustration of what economists call an equity/efficiency trade-off. In other words: we cannot have it all. As long as we design interventions that are going to privilege the rich, even if we improve overall health, we will be widening the gaps between health haves and health have nots.

Recognizing that we cannot have it all, is this trade-off acceptable to us? At heart this comes down to our values. Do we simply care about average health, even at the expense of one group?

We suggest that inequities should matter. Inequities are the result of systematic injustice—in this case of unequal access to healthcare settings where marketing and vaccine delivery occurred; either way, some are left behind. Public health must not allow lopsided interventions and approaches to happen—even if it comes at the expense of better overall health.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

TO SCAN OR NOT TO SCAN

Half a million children arrive at emergency rooms following minor head trauma each year, and almost half of them receive a CT scan of the brain. Because only rarely is the information gleaned from the CT valuable, a large number of children are getting radiation exposure. Who should get a scan remains a difficult joint doctor-parent decision. These authors randomized parents to receive either a guided conversation with pictures about concussion and how to think about the true risk of serious brain injury (called a decision aid) or to receive usual ER care. Providing parents with a clear decision aid improved parental knowledge, limited unnecessary follow-up CT scans, and involved parents more deeply in their child’s care.

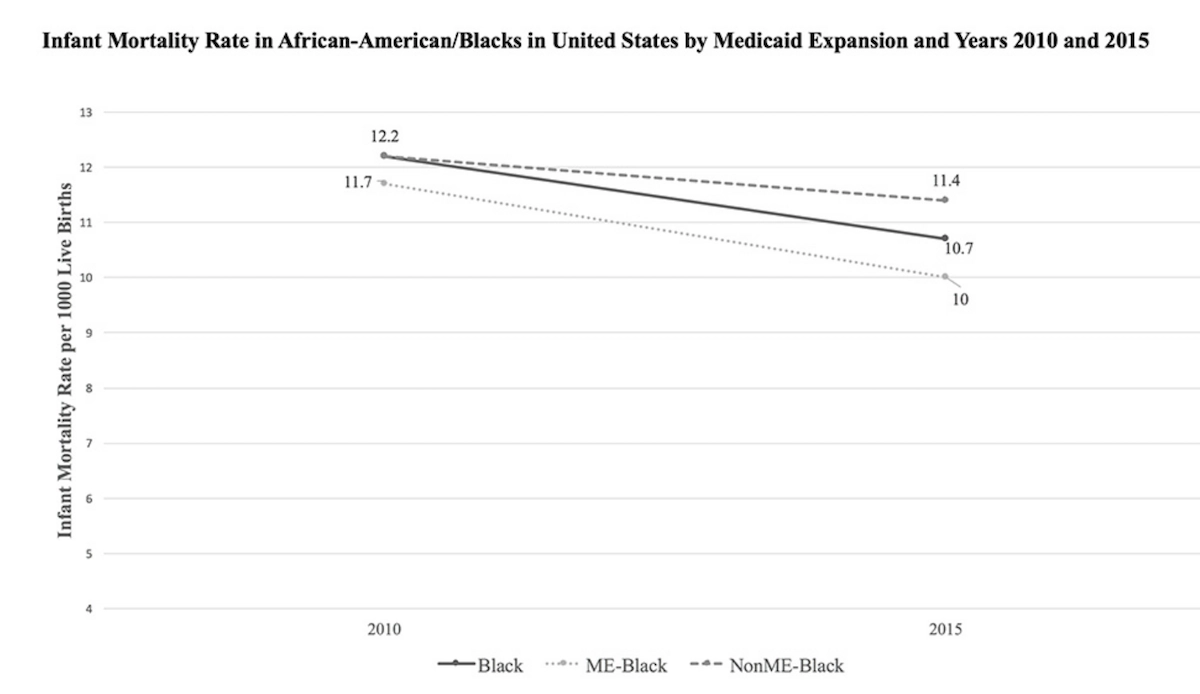

INFANT MORTALITY AND MEDICAID EXPANSION

Medicaid funds many maternal and child healthcare services in the United States, including 45% of births. Since the Affordable Care Act was implemented in 2014, 34 states have opted to expand their Medicaid programs. But some of the states with the largest proportions—54% to 72%—of births covered by Medicaid did not expand. As of 2016, several of those states, including Alabama and Mississippi, had the highest rates of infant mortality in the country at about 7.4 to 9.1 infant deaths for every 1000 live births.

Bhatt and Beck-Sagué compared infant death rates between states that expanded Medicaid coverage and those that did not. Average death rates among all infants decreased in states that expanded Medicaid, and increased in states that did not.

As shown in the Figure, Black infant mortality decreased overall from 2010 to 2015, but twice as much in Medicaid expansion states (a difference of 1.7 deaths per 1000 live births) compared to non-expansion states (a difference of 0.8 deaths per 1000 live births).

The researchers call for studies to further identify reasons why Medicaid expansion states had better infant outcomes, and what barriers to child health may exist in non-expansion states. —Sampada Nandyala, PHP Fellow

Graphic from “Medicaid Expansion and Infant Mortality in the United States,” Chintan B. Bhatt and Consuelo M. Beck-Sagué, American Journal of Public Health, April 2018, Vol 108, No. 4.