Toward a Muscular Public Health

Why does public health seem to revel in an approach that is at odds both with notions of individual freedom and with norms in medicine?

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Toward a Muscular Public Health

Public health often offers directives. You should wear seat belts. You should get vaccinated. You shouldn’t smoke. This command language, with its moral tinge, is at odds with the language of shared decision-making that has become central in the medical world and in some ways may marginalize the message of public health.

Why does public health seem to revel in an approach that is at odds both with notions of individual freedom and with norms in medicine? In the shared decision-making world of modern medicine, doctors are meant to discuss options with patients, the final health decision is made by the patient, who may in the end, make an unhealthy choice. But public health persists in suggesting courses of actions for the entire population.

Why? And is this ok?

The answer is astonishingly simple. Public health professionals know best for populations; individuals know best for themselves.

Let’s use smoking cigarettes as an example. As public health professionals we are delighted that the prevalence of smoking has decreased from 50% to 16% in the past five decades. A future elimination of all tobacco use would please us even more—the end of smoking would save millions of more lives.

Shared decision-making is necessary at medical visits; clinical providers may be experts, but the best data about treatment may not apply to the patient in the office, and so outcomes are always in doubt. Hence, the patient can reasonably choose for herself among a number of uncertain options.

Fortunately, we can be much more certain about the outcome when we are looking at populations. By any reasonable measure—longevity, cost to the health system, quality of life—smokers do worse than non-smokers. We say this with certainty. After we assemble incontrovertible evidence, as public health providers we try to universalize its application for the good of others. We tax cigarettes, we institute anti-smoking advertising campaigns, and we increase insurance premiums to smokers to create a healthier population.

Society entrusts public health to understand what is in the public good and to act on it. Therefore, when we know the healthiest answer, we should be relentless in seeking its implementation. It is up to society to decide if public health should or should not be in a position to flex our muscles. But, when we see opportunity to improve the public’s health, which derives from the combination of evidence and public agreement, we should act. And we should admit that such flexing is at odds with shared decision-making ideals. That is nothing to be ashamed of.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

RURAL COMMUNITIES AND MENTAL HEALTH NEEDS

Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) is an eight-hour program that teaches people with no clinical training how to respond to signs of mental illness and substance use, similar to community-based CPR training intended to reduce cardiac deaths. Begun in Australia to reduce community stigma and to assist peers in advising friends, neighbors, and co-workers to get professional help, MHFA is now widespread in rural communities in the United States. However, the program has still not undergone rigorous evaluation here, where limited behavioral health options are already stretched.

HEALTHY TAXES

The Federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is the largest anti-poverty program we have and among the most effective, especially for reproductive-age women. Recipients earn a tax credit that varies with the level of earned income, encouraging employment. For the past 30 years individual states have introduced their own EITCs, and 26 states now have programs that may affect health as well as women’s income. These researchers found that the greater the generosity of a state’s EITC, the greater the increases in overall infant birth weight, a key predictor of infant mortality and later childhood outcomes. The measured health benefit of EITCs is similar to increases in birth weight produced by the income boost of minimum wage laws.

WHAT THE FRACK?

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is the process by which natural gas and oil are extracted from underground reservoirs using specialized drilling processes. The United States’ largest source of natural gas comes from the Marcellus Formation, 104,000 square miles of underground shale rock that spans Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia.

In some communities fracking is an essential boom for local economies that brings jobs, higher wages, and lower unemployment rates. But the fracking industry can also have a negative effect on boom communities.

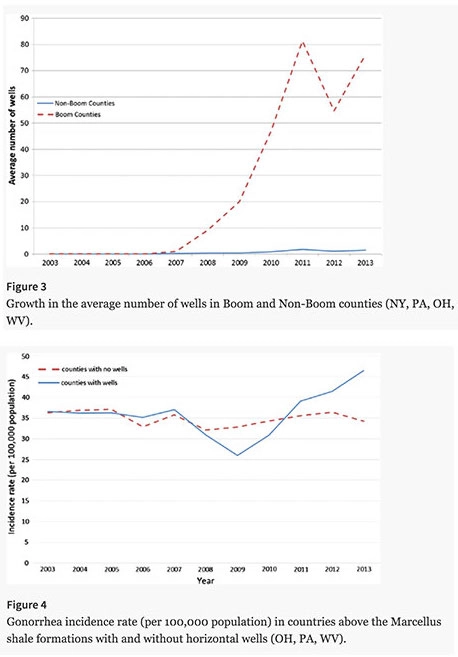

A 2017 study conducted by Komarek and Cseh found fracking activity in boom counties to be associated with a 20% increase in new gonorrhea cases between 2003 and 2013.

The top graph provides a timeline showing boom counties experienced a rapid increase of new wells starting in 2006. The contrast with non-boom counties is stark. The second graph (figure 4) shows a divergence in the number of new gonorrhea cases per year in counties with and without fracking. The beginning of the divergence corresponds with the onset of fracking activity in 2006. Although rates decrease in the first three years of fracking, there is a dramatic 20% increase in the last four years.

The United States spent $15.6 billion in 2008 on treating sexually transmitted infections, with $162.1 million spent on gonorrhea alone. The 20% increase in gonorrhea rates in the Marcellus Shale region is much higher than the 2-3% increase observed across the country. Only diagnosed cases can be recorded by the CDC, which means the true number of people affected is under-reported. This report demonstrates another way that fracking changes communities. Young male workers arrive to perform newly available work, alcohol use increases, and sexually transmitted infections rise. — Erin Polka, PHP Fellow

Feature image: (Top graph figure 3) Growth in the average number of wells in Boom and Non-Boom counties (NY, PA, OH, WV). (Bottom graph figure 4) Gonorrhea incidence rate (per 100,000 population) in countries above the Marcellus Shale formations with and without horizontal wells (OH, PA, WV), Komarek, & Cseh, Journal of Public Health Policy (2017) 38: 464. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-017-0089-5