The Socioeconomic Divide Goes to the Gut

Individuals with household incomes below $50,000 per year had less diverse gut microbiomes compared to those with higher annual incomes.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

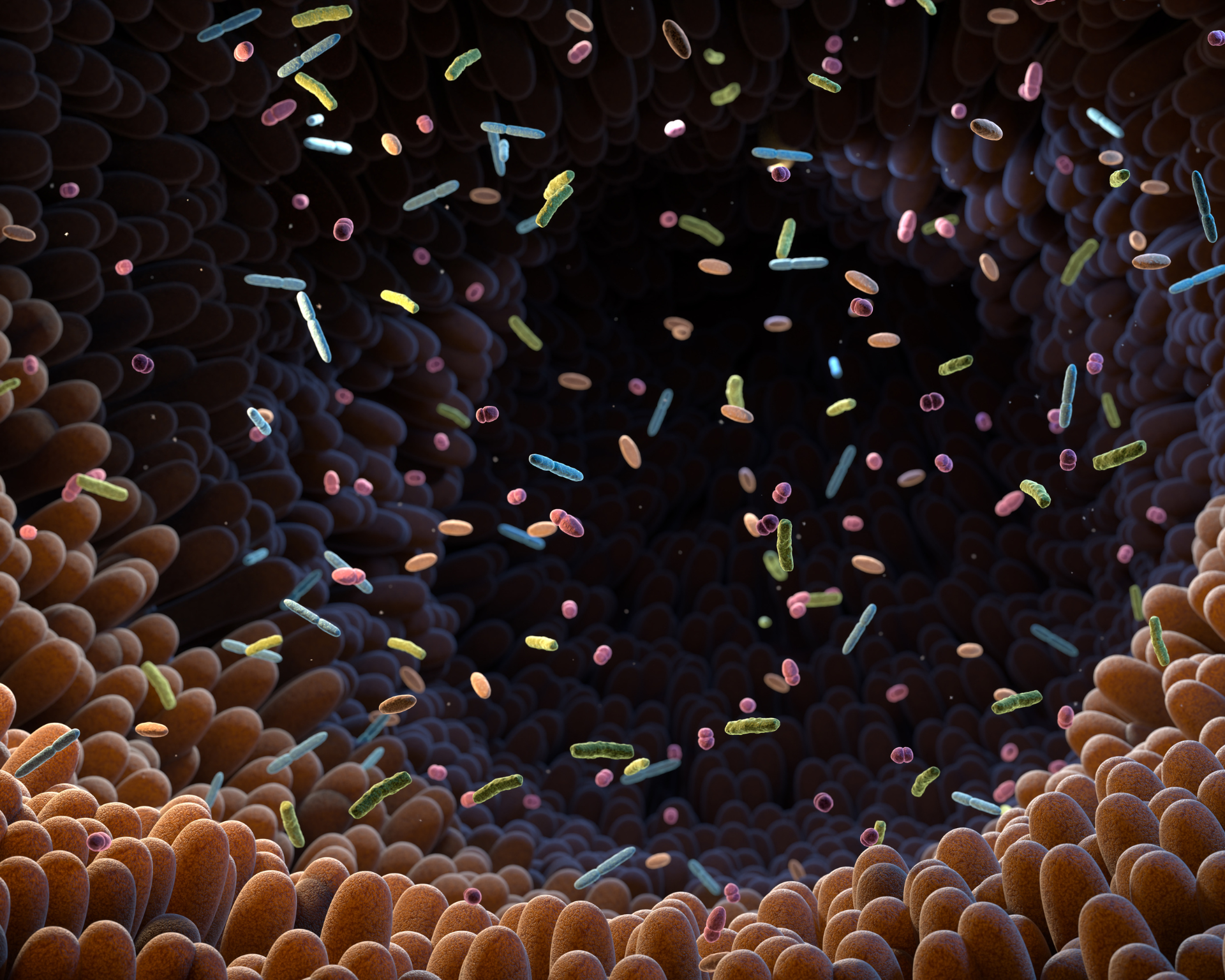

You might not think your income or where you live have much to do with the tiny living things in your gut. However, your socioeconomic status – factors like education, job, and neighborhood – can profoundly influence the trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi that reside in your digestive system. This complex community of microorganisms, known as the gut microbiome, plays a crucial role in overall health and well-being.

The gut microbiome plays a pivotal role in digesting food, protecting against pathogens, and regulating the immune system. A diverse community of gut organisms is generally considered healthier; reduced variety in the microbiome can impact metabolism and mental health. Reduced microbiome diversity has also been associated with various health problems, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and digestive disorders.

Soyoung Kwak and her colleagues explored how socioeconomic status affects our gut inhabitants by analyzing the gut microbiomes of 825 persons from diverse racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds in the United States. Using gene sequencing of stool samples, they examined how factors like education, occupation, and neighborhood characteristics related to the diversity and types of gut bacteria present.

Their findings were striking. Participants with household incomes below $50,000 per year had significantly less diverse gut microbiomes compared to those with higher incomes. Certain bacteria, such as Prevotella copri and Catenibacterium, were more prevalent in lower-income groups. These bacteria have been associated with inflammation and metabolic disorders. Conversely, higher-income individuals had more Dysosmobacter welbionis, which has been shown to protect against obesity and metabolic dysfunction in animal studies.

As our understanding of the “sociobiome” grows, it may open new avenues for creating more equitable health outcomes across all socioeconomic levels.

Several factors contribute to these differences in gut bacteria across socioeconomic groups. Diet plays a major role. Many low-income neighborhoods are “food deserts” – areas with limited access to fresh, healthy foods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 70.2% of low-income neighborhoods have fewer healthy food options compared to wealthier areas. This often leads to a reliance on processed, high-sugar low-fiber foods that can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, favoring the growth of inflammation-associated bacteria, while reducing the abundance of beneficial fiber-fermenting bacteria. Over time, these imbalances in the gut microbiome can contribute to chronic health conditions that disproportionately affect lower socioeconomic populations.

Chronic stress, more prevalent in lower-income communities due to financial hardship, discrimination, and other social determinants of health, also affects the gut microbiome. Researchers Annelise Madison and Janice Kiecolt-Glaser found that stress hormones and inflammation can disrupt the balance of gut microbes, potentially leading to a “leaky gut,” allowing harmful substances to enter the bloodstream.

Based on these findings, Kwak and her team propose targeted interventions to address socioeconomic disparities in gut health. They emphasize improving access to fresh, affordable foods in underserved neighborhoods through initiatives like community gardens and farmers’ markets. These efforts could help diversify the gut microbiomes of residents in low-income areas, potentially reducing their risk of inflammation-related health issues.

The researchers also recommend implementing stress-reduction programs in schools and workplaces, particularly in lower-income areas. Given the link between chronic stress and gut microbiome disruption, such programs could have a significant impact on gut health in these communities.

On a policy level, the researchers advocate for increasing funding for nutrition assistance programs and expanding Medicaid coverage to include preventive health services focused on diet and stress management. These measures focusing on the “sociobiome” – the intersection of social conditions, gut microbiome, and health – could help address what could be one of the root causes of population health differences: gut microbiome disparities.

This field of study is still in its infancy, with long-term health impacts yet to be fully established. However, these findings highlight the potential importance of gut health in addressing broader health inequalities. As our understanding of the “sociobiome” grows, it may open new avenues for creating more equitable health outcomes across all socioeconomic levels.