The Poor People's Campaign

This week fifty years ago, Martin Luther King’s ambitious project, the Poor People’s Campaign, ended

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

The Poor People’s Campaign

This week fifty years ago, Martin Luther King’s ambitious project, the Poor People’s Campaign, ended. In 1968, Dr. King had encouraged the civil rights movement to broaden its target from Jim Crow protests to demands for full employment and housing and guaranteed basic income, “an economic bill of rights.” The plight of the impoverished, Dr. King knew, crossed racial lines and his campaign was purposefully multiracial. But Dr. King’s very association with a poverty campaign implied that poverty was a racial problem, which implied, and still implies, a moral problem.

There seems to be little question that poverty is a moral problem and that should be enough to focus our attention. And yet, approaching poverty as a moral issue polarizes Americans. The public health data that has accumulated since Dr. King’s death allows us, perhaps, to change the paradigm of poverty. If we can agree that poverty is a public health problem similar to, say, smoking, then it can be tackled as a solvable policy problem, adding weight to our efforts to address it.

The gap in life expectancy between the richest 20% and the poorest 20% of American men is nearly 15 years. Hundreds of thousands of deaths each year are linked to poverty-related causes. Those with low incomes have higher rates of accidents, injuries, depression, diabetes, substance use, and the list goes on. Poverty kills. There is no area in population health where the evidence is so clear: if you wish to be healthy you should choose to be born to wealthy parents.

Importantly, we can improve this. We know that life expectancy for those with the lowest incomes can be improved by government expenditures, which suggests that health policies make a difference.

And yet, the link between health haves and health have nots, directly mapping onto those who are wealthy and those who are poor, not only persists, but has widened in this country. Five decades after Dr. King, one of public health’s central goals should be to drive the political conversation around poverty. No political candidate or party should be allowed to ignore the subject. While the moral argument against poverty remains robust, we suggest that a public health perspective lends heft to our efforts to tackle poverty and should be front and center in all national discussions of this issue.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

IT’S YOUR BIRTHDAY: YOUR TEST KIT IS IN THE MAIL

Persons turning 50 should be screened for colon cancer to reduce the chance of developing and dying from cancer. But Latinos, Blacks, and Medicaid enrollees have lagged in screening rates. Choices for screening include the more invasive, expensive colonoscopy (which requires ongoing medical care) or the annual stool cards, which may be more convenient for populations with barriers to care. This study describes screening across the entire insured population of North Carolina. Both screening choices are widely used, but these data suggest that state or county health departments could improve population health by mailing a reminder and stool card kit to encourage screening among members of minority groups.

GOLDILOCKS AND THE PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM

Health inspections, mandated by states, happen every day without us noticing. Local health departments are responsible for food establishment inspection, sewage disposal, private well inspection, and child lead poisoning prevention, but the scope of such services varies by local health department. Cost effectiveness studies in every industry depend on establishing costs and describing outcomes, but such evaluations of public health services have rarely been done because there are so few studies of cost. This costing study demonstrates that even at the local level there are economies of scale, suggesting that mergers of small local health departments or specialization by department could save taxpayers money.

ARE HOSPITALS SPENDING ENOUGH ON THE COMMUNITY?

Nonprofit hospitals are tax exempt in exchange for providing benefits to the communities where they are located. These exemptions allow nonprofit hospitals to keep $24.6 billion a year. One debate within the health policy community is whether these nonprofit hospitals invest enough in community health initiatives to compensate for exemption status.

A recent study by Gary Young and colleagues of the Center of Health Policy and Healthcare Research used data filed with the IRS by nonprofit hospitals to track spending on patient care benefits and community health. Patient care benefits include spending on financial assistance, unreimbursed costs for implementing government programs, and subsidized health services. Community health benefits are nonclinical initiatives that target social determinants of health. For example, Kaiser Permanente gives out HEAL grants to organizations that promote or offer healthy food and physical activity in underserved communities.

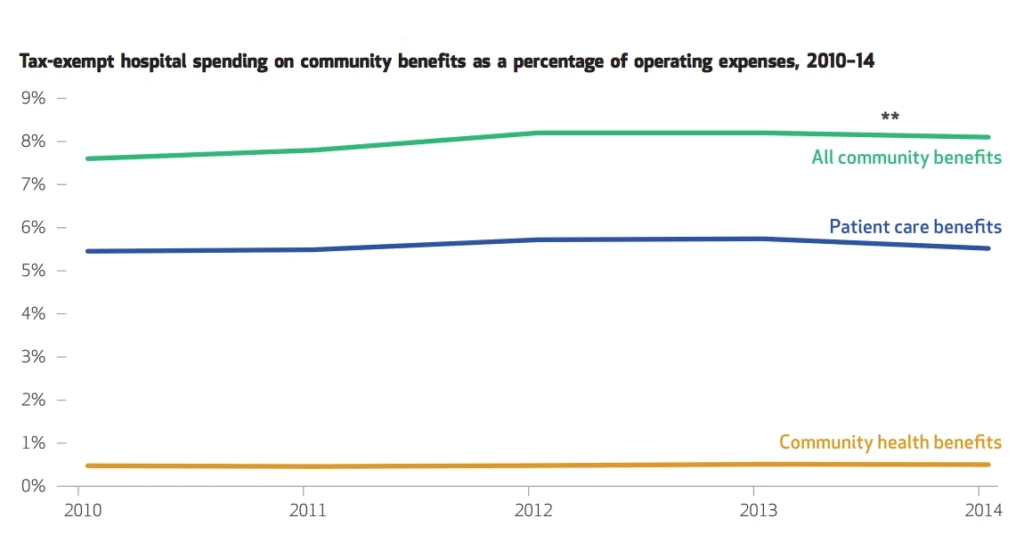

The graph above shows that spending increased from 7.6% to 8.1% from 2010 to 2014 after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). However, the increase was mainly driven by spending on patient care benefits between 2010 and 2012 whereas spending on community health initiatives remained essentially unchanged during the four years.

The ACA tried to improve population health by requiring nonprofit hospitals to conduct community health needs assessments. The objective of these assessments was to encourage hospitals to invest more in initiatives to prevent illness and improve community health as a means of reducing expenditures on direct patient care. But this shift in spending did not happen. These data show that hospitals continue to focus their spending on patient care rather than on programs that address community-wide public health challenges.

—Qing Wai Wong, PHP Fellow

“Community Benefit Spending By Tax-Exempt Hospitals Changed Little After ACA,” Gary J. Young, Stephen Flaherty, E. David Zepeda, Simone Rauscher Singh, and Geri Rosen Cramer. Health Affairs Vol. 37, NO. 1, Published: January 2018 https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1028