The Persisting Racial Inequities in Food Insecurity

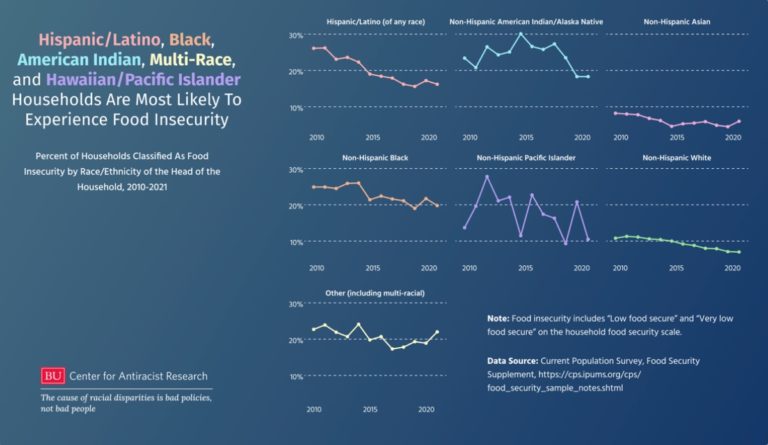

According to 2021 data, over 20% of Black, 15% of Latino, and 15% of American Indian households experience food insecurity, while only 7% of White families experience food insecurity.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

In the U.S., around one in seven households worry about having too little to eat. Families who are food insecure have poor access to nutrient-dense food, which contributes to a variety of chronic health problems, such as cardiovascular disease. Children who live in food insecure households are particularly vulnerable as a lack of nutritious food adversely affects their cognitive growth.

According to the earliest trackable data for food security, Black and Latino families are consistently more likely to experience food insecurity. This can take the form of cutting meal size, running out of food quickly, being unable to buy more, or not eating for a whole day. Although the general trend of food insecurity has dropped since 2010, the racial gap has been consistent.

The latest data from 2021 shows that over 20% of Black, 15% of Latino, and 15% of American Indian households experience low or very low food security. In contrast, only 7% of White families are in the same situation. In other words, White families are three times less likely than Black families to experience hunger.

Structural racism drives persistent food insecurity for marginalized racial groups. Black and other racial minority groups have long been trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty due to discrimination in education, employment, income, and assets. Poverty and discriminatory policies like redlining have contributed to families residing in “food deserts” where grocery stores selling nutritious food are difficult to reach due to distance or lack of transportation.

Economic shocks, such as those seen during COVID-19, may make communities of color more vulnerable to food insecurity. Increasing family income has proven to be one successful policy remedy. For example, monthly income checks of up to $300 per family reduced food insufficiency among families with children by 26% during the pandemic.

However, these successes were only temporary, as the pandemic relief checks stopped in December 2021. No notable efforts have been made at the national level to enact a similar policy. Bringing back national cash assistance policies for families, along with lowering application and extension difficulties for existing programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are key steps toward curbing hunger among marginalized racial groups.

Databyte via the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research

Public Health Post is collaborating with researchers at the Center for Antiracist Research Racial Data Tracker to produce a series of articles focused on structural racism and health. This is the third article in the series.

The goal of the Racial Data Tracker is to collect, analyze, and publicly share data on racial inequities and disparities with communities and individuals interested in using racial data for research, advocacy, education and policy. The data will be available through downloadable data tables, infographics, and interactive visualizations. The project will publicly launch in Spring 2023.