The Cost of Diagnostic Delay in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Females and gender-diverse patients tend to face greater delays in autism diagnosis than their male and cisgender peers.

Read Time: 2 minutes

Published:

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by persistent social and behavioral challenges—and has nearly tripled in the United States over the past two decades. While the trend may seem alarming, it also reflects expanded diagnostic criteria, heightened public awareness, and widespread screening measures to recognize autism. Despite these advances, significant diagnostic delays still persist.

Autism can be identified as early as age 2, but many are diagnosed much later. Delays occur because autism exists on a wide spectrum, encompassing diverse traits such as attention difficulties, sensory sensitivities, and social differences. The variability in presentations makes autism difficult to diagnose in a single evaluation, leading to misdiagnoses of ADHD or sensory issues rather than recognizing a broader autism profile.

Early detection is transformative. When diagnosed in childhood, individuals are more likely to access behavioral therapies and support services to help improve daily functioning and long-term wellness. A diagnosis after age 12 is further linked to greater mental health challenges, with those diagnosed as adults nearly three times more likely to develop psychiatric conditions than those diagnosed in childhood.

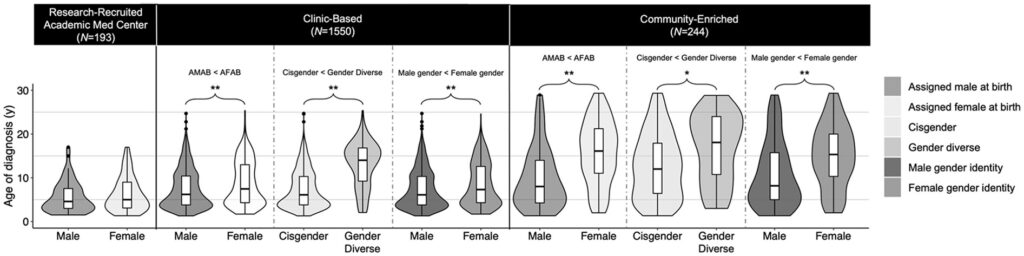

To examine gender-related diagnostic delays, Goldie McQuaid and colleagues examined 1,987 autistic individuals across three groups: research-recruited youth, clinic-evaluated youth and young adults, and a community sample of adults. The researchers assessed how sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and gender diversity status (gender-diverse vs. cisgender) influenced the timing of autism diagnosis.

The results revealed consistent disparities, as shown in the figure above. In both clinic and community patients, females were diagnosed significantly later than males—on average, 1.3 years later through clinical evaluation and 5.8 years later in community settings.

Gender diversity caused even greater delays. Among clinic-based youth, gender-diverse patients received a diagnosis nearly 5.7 years later than cisgender peers. In contrast, no diagnostic disparities were seen in research-recruited patients, likely because standardized diagnostic criteria helped minimize gender-related bias.

The findings reveal important limitations in clinical approaches to diagnosing autism, particularly in females and gender-diverse patients. While international clinicians encourage autism screening for gender-diverse youth, widely used diagnostic measures like ADOS-2 and ADI-R were validated using young cisgender males. Thus, these tools may be less sensitive to female and gender-diverse presentations of autism. Updating diagnostic practices to reflect age and gender diversity is a crucial step toward reducing diagnostic delays and enhancing long-term health outcomes for neurodiverse individuals.

This is the first part of a three-part series on autism spectrum disorder.