The Census and Public Health

The US Constitution mandates that every resident be counted at least every ten years.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

The Census and Public Health

The US Constitution mandates that every resident be counted at least every ten years. As the 2020 census approaches, the Trump administration’s decision to meddle with how to perform this head count by adding a question about citizenship to the census has already been criticized by the Census Bureau’s Scientific Advisory committee and has become the target of lawsuits.

What has provoked the Trump administration to add this question appears to be political representation. The new census question appears to be an attempt to depress the 2020 population count in immigrant-rich and predominantly Democratic areas in advance of redistricting in 2021. The Justice Department’s argument that it needs more detailed citizenship data to better enforce the 1965 Voting Rights Act has the same flavor as North Carolina legislators’ recent voter identification bill, which was nominally aimed at voter fraud, but actually targeted African Americans with voting restrictions. In both these cases, tying population data to law enforcement makes some worry that as many as 24 million people will not participate and get counted—those who owe child support or are behind on student loan payments, as well as fugitives, for example—because they fear their names and addresses might be shared with police. Nearly nine million legal US residents live with an undocumented person, and what if they ignore the census or undercount their households?

We do not know the effect of adding a citizenship question. It has never been tested, even in a pilot study. But we do know that these data will influence political representation—seats in Congress, electoral votes—which can influence how and if health disparities get addressed legislatively.

So, as a matter of public health, should our health organizations and public health professional groups and schools actively get involved?

Accurate census data are critical for the public’s health. These data drive, for example, federal grants to states for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for women and low-income children at nutritional risk. They determine funding for Medicaid and for school lunch programs. They guide disaster response and disease outbreak planning. The CDC uses census information to locate geographic areas with low education levels and high poverty rates so as to expand screening and outreach programs. These data inform the building of roads, schools, and health centers—what public health cares about. Eight hundred billion dollars of federal funding is allocated based on census data.

Not participating in the census in support of those too afraid to participate seems counterproductive to us. Actively encouraging members of disadvantaged and minority populations to participate in the US census may be a more positive approach as these groups are historically undercounted. All of us leaving the answer to a citizenship question blank also seems reasonable as a means of rendering it meaningless, but debating the options is what public health practitioners should do first.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

POLICE POLICY

In this era of body cameras, mental health training may improve how police officers respond to situations involving persons with mental health problems. Researchers in England randomized 12 police stations to test the effectiveness of a one-day, professional mental health training for frontline police officers, in contrast to routine training. Police who received this specialized training were better at recognizing mental health issues during incidents in the subsequent six months. The best training design, delivery, and content for training police remains unclear, but this work shows conducting research trials within police settings is feasible and might be acceptable in the United States.

HOW A LEGISLATURE GETS ACTIVE

Changing public policy is one strategy for addressing physical inactivity among children and adolescents. But it is as hard to change policy as it is to get children to exercise 60 minutes a day. This case study describes the development, advocacy for, and passage of Georgia’s SHAPE act, which took six years to unfold and required fitness assessment and physical education for school children to increase their physical activity. Data documenting Georgia’s poor state ranking in childhood obesity were important, but progress was made only after re-framing the legislation as fitness promotion rather than obesity prevention. Bipartisan political support and sponsorships were keys to legislative success here, spurred by diverse community partners, and citizens reached by grassroots outreach and advocacy.

HOME-BASED UPGRADES FOR THE ELDERLY

As people age, day-to-day activities like dressing, bathing, walking up and down the stairs, and managing medications tend to become more difficult and, as a result, more dangerous. Around $219 billion per year is spent on long term care for those whose ability to function independently is impaired.

One alternative to costly assisted living programs or nursing homes is the Community Aging in Place, Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) program. CAPABLE aims to help elderly persons with physical disabilities overcome individual or environmental limitations so as to “age in place,” which the US Centers for Disease Control defines as “the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level.”

As Sarah L. Szanton and her research team found in their study of the effectiveness of the CAPABLE program, health outcomes can improve through home upgrades. In this home-based care model, participants set goals with a registered nurse and an occupational therapist related to independent functioning, and a handyman installs assistive devices, completes home repairs, and increases the safety and overall navigability of homes.

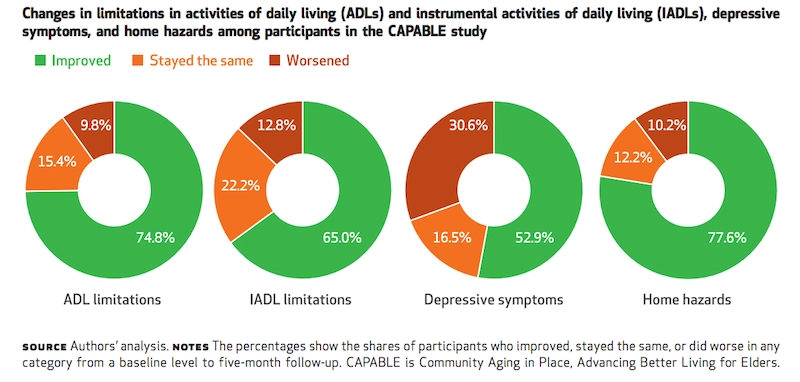

At the end of CAPABLE’s five-month program, 75% of participants were better able to carry out their “activities of daily living” (ADLs). On average, participants were able to halve their difficulties with ADLs, which also reduced symptoms of depression.

Based on these results, the broad use of home-based modifications for those with physical disabilities can save older adults and their families money on housing and health care alongside much-needed improvements in quality of life and mental health. —Madeline Bishop, PHP Fellow

Graphic from Health Affairs Vol. 35, No. 9, “Home-Based Care Program Reduces Disability and Promotes Aging In Place,” Sarah L. Szanton, Bruce Leff, Jennifer L. Wolff, Laken Roberts, Laura N. Gitlin, September, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0140