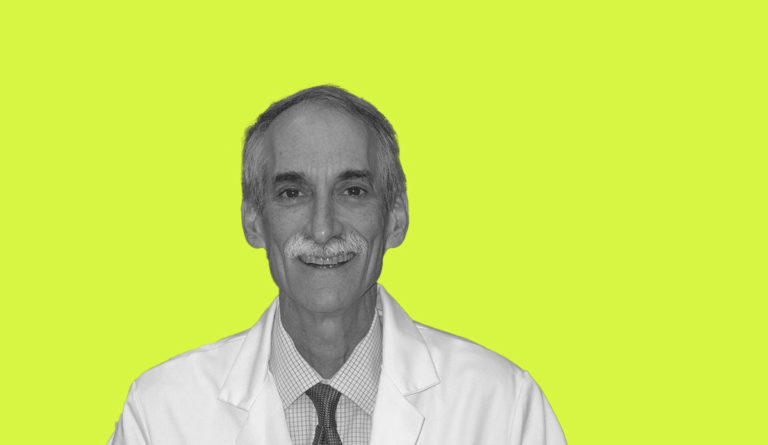

Stephen Salloway

Alzheimer's researcher Stephen Salloway talks about caregiving, conquering stigma and why there's hope in this work.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Stephen Salloway, director of neurology and the memory and aging program at Butler Hospital and the Martin M. Zucker Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Brown University, is a global leader in Alzheimer’s research.

Alzheimer’s disease and treatment options have been appearing in the American news with increased visibility over the path few months, but this field has been Salloway’s expertise for decades. But Salloway always has an eye on the effect of this increasingly common illness on families, and he brings to this concern a global perspective. “In many other countries with socialized medicine they are more mindful of caregiving,” he says. Salloway explains that in some other countries, Alzheimer’s diagnoses are immediately followed by a visit from a social worker to develop an individual care plan, and “it is all covered by their health insurance.” In the U.S. people can find geriatric care planners, which Salloway notes as improvement of care from decades ago, but their work is neither covered by Medicare nor by most private insurance plans.

Families fill in those gaps. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, 83% of the help provided to older adults comes from family, friends, and other volunteer caregivers. That is $256.7 billion worth of labor that goes unpaid. Salloway knows, “Alzheimer’s, really affects the family.” This is why Salloway wishes that more professional care was covered by insurance as the effect of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis reaches beyond patients to caregivers as well. “It can be rewarding for families, but it is expensive and draining.”

So, who are the primary caregivers for adults with Alzheimer’s? “Two-thirds of caregivers are women, ” Salloway responds. He pauses momentarily before continuing. “I don’t want to stereotype, because there are great male caregivers.” He nodded before confessing. “But I think women have a more natural affinity for it. They are a little more intuitive about, if it is a family member, what their family member needs and how to provide it.”

How did a man such as Dr. Salloway develop a passion for Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia? He began as a caregiver. “My grandmother had dementia when I was a boy and I was involved with every stage of her illness.” He spoke about his grandmother’s transition from her apartment, to his childhood bedroom, and then to a nursing home. “I saw the effect that it had on her and all of us,” he said, revisiting the memory of his grandmother’s life. Her life and illness were the impetus for his nearly fifty-year career in neurology. He explained, “My goal has been to help open the modern era of treatment for Alzheimer’s so that Alzheimer’s is treated like all other major diseases. We diagnose early, and we try to modify and prevent the disabling features of the disease.”

As health professionals, we may forget the stigma that marks an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, but Salloway assures us that it is present. “That is the most feared diagnosis for older people. If you tell someone that they have Alzheimer’s, some people think that it is a death sentence.” Millions of older adults face their greatest fear each day in the United States. Approximately 5.8 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease, a number that is projected to increase to 14 million by the year 2060. Salloway continues. “Some people immediately think of the disabling phase of the illness, especially if they have had it in their family. If they have cared for their mother or father, they know what is coming. It is frightening.”

How does one mitigate this fear and stigma? “Just talking about it is good. You asked me for my best advice earlier. It is just talking about Alzheimer’s openly and realistically,” says Salloway. His passion is apparent. “If you are dealing with stigma, you want to overcome it by being open and working through the issues. Work through the fear.”

With an optimistic grin, Salloway begins to share the progress of psychiatry and neurology that he has seen throughout his career. “We are definitely improving our diagnostic ability. Soon there will be blood tests to diagnose Alzheimer’s. We are going to be diagnosing much earlier and more reliably in the future.” Salloway believes that the diagnostic options will incentivize people to be diagnosed earlier and that with new treatment, patients and families will be “encouraged that there is more hope.”

Photo provided