Standing for Native American Health Care Equity

This Thanksgiving, Americans will imagine an almost mythological scene of pilgrims sharing a meal with the Plymouth natives. A more accurate portrayal of Native-settler relations is on display over the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

This week Americans will imagine an almost mythological scene of pilgrims sharing a meal with the Plymouth natives. This Thanksgiving, however, a more accurate portrayal of Native-settler relations is on display. The Standing Rock standoff regarding the Dakota Access Pipeline reflects the longstanding tension between Native American livelihood and European American ideals of progress and industry. It further reflects the complex relationship between Native American nations and the U.S. government—where tribes have relative sovereignty but are still very much under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

This complex relationship is likewise reflected in healthcare provision for Native Americans. The 1976 Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which was recently reauthorized, aimed at “providing the highest possible health status to Indians and to provide existing Indian health services with all the resources necessary to affect that policy.” The U.S. Government has failed tremendously in these aspirations, as

Native Americans have enormous health inequities along with generally inadequate access to needed services . These inequities include much higher rates of tuberculosis (750% higher), diabetes (420%), accidents (280%), and suicides (190%). In addition, alcohol and drug problems are significantly higher than the general population, including 7-8 times higher rates of alcohol-related deaths than the general population and the highest opioid overdose rate among racial/ethnic groups in the nation.

I should pause at this point to reflect upon my discomfort in drawing attention to these inequities. On one hand, these inequities are alarming and deserving of urgent attention among policy makers and the healthcare industry. On the other hand, Native Americans are understandably sensitive to their communities being framed largely in terms of deficits and disorders. A deficits-model stings all the more given that these health inequities are inextricably connected to the ongoing legacy of European-American colonization. The standoff at Standing Rock, with solidarity from indigenous peoples across the globe, is a powerful reminder of the strength and resiliency of indigenous populations in defending their livelihood against colonial forces over the course of generations.

It is, then, with recognition of both the resiliency and need of Native populations that I make a few comments about healthcare challenges. These comments are based on my experiences as a (White) psychologist and addiction researcher working with Native Americans in the context of mental health and substance use considerations. I stress that these remarks are not exhaustive, and that I am not an expert on healthcare policy.

1. It may come as a surprise that about 70% of Native Americans live off of reservations in urban areas. The city with the largest number of Natives is New York City. Urban-dwelling Native Americans have comparable health disparities as their reservation counterparts but also less access to social support and adequate culturally-appropriate health care services. There are 34 urban Indian health organizations which play a major role in health service provision for urban Natives, but many do not live close enough to access these services. In addition, these urban organizations receive only 1% of an already paltry Indian Health Service budget. Further, these organizations may struggle to balance preserving Native traditions in a pan-tribal setting.

2. Existing treatments for mental health and substance use—including nearly all treatments deemed as “evidence-based”—are not culturally-relevant for American Indian populations. Only in a few instances have clinical trials for American Indians been conducted, and so there are reasons to be skeptical about the feasibility and generalizability of existing treatments. A major reason for this skepticism is the pervasive narrative of “culture” among American Indian communities; a constant refrain in Indian Country is “our culture is our treatment”—pointing towards cultural reclamation for healing.

Nonetheless, it remains crucially important to Native communities that these medications are provided as just one part of comprehensive culturally-appropriate services. Native service providers and communities commonly stress the importance of cultural reclamation, historical or generational trauma, family relationships, and spirituality.

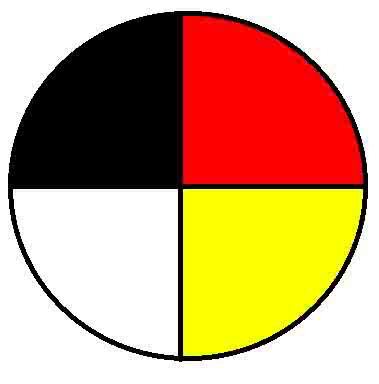

3. At the same time, American Indians generally are pragmatic, and most acknowledge the importance of Western treatments so long as they are provided in the context of healing broadly. Pictured here is the traditional medicine wheel, which has become a pan-tribal symbol of holistic health (encompassing the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual). Western interventions may be seen as being necessary, at the very least, to aid physical dimensions of healing. For example, although many Native communities and individuals have been historically reluctant to use medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders, interest in these medications has swelled in recent years (in the context of how devastating opioid addiction has been in some communities). Nonetheless, it remains crucially important to Native communities that these medications are provided as just one part of comprehensive culturally-appropriate services. Native service providers and communities commonly stress the importance of cultural reclamation, historical or generational trauma, family relationships, and spirituality.

4. Native communities would benefit from greater support in their own efforts to implement, adapt, and/or develop mental health and substance use interventions in a culturally-appropriate and relevant manner. An important form of research towards this end is community-based participatory research, in which community and academic partners collaborate in all phases of the research process and share power and responsibility, ensuring that research aims, design, and results are relevant and culturally-appropriate.

It has been heartwarming to see so many non-Natives stand alongside those at Standing Rock, whether in person or in spirit. It is my prayer that this solidarity with Native populations continues, and that allies likewise fight alongside Native Americans for the U.S. government to take seriously its commitment to provide “the highest possible health status” to Native Americans. This will require a much greater allocation of resources as well as greater appreciation of the roles of cultural and strengths-based approaches.

Featured image: Peg Hunter, #No DAPL – Stop Dakota Access Pipeline, Marching down Market St, San Francisco, November 15, 2016, used under the CC BY-NC 2.0. Image: hurdygurdygurl, Medicine Wheel, used under CC BY 2.0