Public Health’s Compensation Crisis

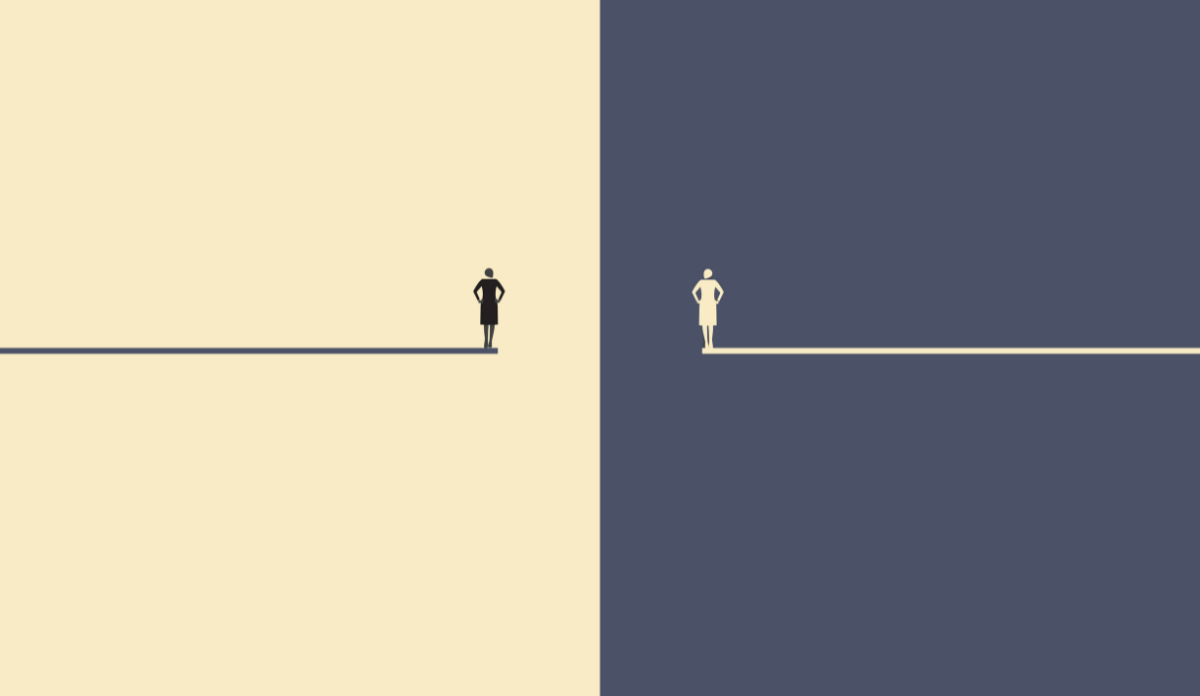

The U.S. is facing a mass exodus of young public health workers. Salary discrepancies between the private and public sectors are not helping the problem.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Government public health departments are severely understaffed. If state and local health departments want to successfully deliver the most basic of health services, some policymakers suggest they need to hire 80,000 more full-time employees. The current shortage of personnel limits health departments’ ability to track and respond to cases of infectious and chronic disease.

Many public health students begin their graduate careers with the hopes of promoting health and social justice; naturally, many consider working for the government. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, government health workers have been increasingly vulnerable to harassment at work, blamed for public health failures, and may become less trusted by the public. After reading such accounts, new members of the workforce may instead seek jobs in consulting, biotechnology, clinical research, health insurance, or marketing rather than government jobs.

Graduates may be more willing to work for local and state health departments if they are paid well. Heather Krasna and collaborators contrasted the salaries of public health workers in the public and private sectors. Using survey data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Employment and Wage Survey, they directly compared the average salaries of individuals in similar positions within and outside local and state government.

The team analyzed all careers in public health departments that parallel positions in the private sector; these include epidemiologists, nutritionists, health care workers, mental health specialists, managers, and computer scientists. The researchers found that 30 of the 44 public health positions paid at least 5% less in the public sector than in the private sector. For example, the average epidemiologist in the private sector made $23,000 more than their government-employed counterparts. Workers in management, computer technology, political and environmental sciences, chemistry, and epidemiology faced the biggest salary differences, ranging from 20 to 47%.

Closing the pay gap between public and private employment could help in recruiting and retaining employees.

The U.S. is facing a mass exodus of young government public health workers; salary discrepancies are not helping the problem. A survey conducted between 2017 and 2021 found that three quarters of health department staff aged 35 and younger quit their government public health jobs. Sixty-three percent cited pay as their reason for leaving.

Closing the pay gap between public and private employment could help in recruiting and retaining employees. This will not be an easy task, though, as public health departments mostly run on funding from federal, state, and local governments. While the United States government spends over four trillion dollars on health care each year, government public health activities typically receive only four to five percent of these funds.

Although they may be paid less, health department workers have access to valuable perks; they are more likely to receive benefit retirement plans, medical care plans, and paid sick leave than private company employees in part because they are more likely to be unionized and governed by collective bargaining agreements. Still, many young public health workers prioritize pay over benefits.

For many, the greatest appeal of the health field is public service. Krasna and collaborators suggest that health departments emphasize this shared mission in their recruitment and retention efforts. Health departments can also prioritize employee wellness, which would reduce burnout.

Additionally, researchers suggest that public health departments should advertise workers’ eligibility for the Public Health Workforce Loan Repayment program. New hires can receive contracts to work in a health professional shortage area and receive up to $150,000 in federal loan repayment. If well advertised, this program may help government health departments recruit recent graduates.

Krasna and colleagues urge health departments to adjust their salaries to attract young professionals. Local, state, and federal unions will continue to advocate for increased funding for public health activities and improved salaries for government health workers.