Promoting Housing Stability: Eviction Prediction

Helping the unhoused population requires not only finding stable housing for those without shelter, but also keeping people from losing their homes in the first place.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

Unhoused individuals (people with no permanent place to call home) reached a population of over 650,000 in 2023, a 12% increase from the previous year. Getting people housed through prevention and support programs is a priority for those who are completely without shelter. But less aid is given to housed people who are facing the devastation and health risks involved with losing their homes.

Government initiatives, such as the $1.5 billion distributed through the Homeless Prevention and Rapid Rehousing Program in 2009, played a crucial role in promoting homelessness prevention programs (HPPs) over the past 15 years. Subsequent efforts, like the Housing First model, prioritize stable housing as an initial and foundational step for addressing mental health or substance use disorders for the unhoused.

Popular HPPs include rental subsidies; traditionally “deep” subsidies are offered through housing voucher or permanent supportive housing programs. In one study, 67% of families avoided becoming unhoused when they used their rent subsidy to lease an apartment. Permanent shallow rent subsidies offer lower levels of cash assistance, with discounted rental assistance set monthly. Shelter diversion programs and eviction prevention programs offer immediate alternatives to emergency shelters, help provide financial and legal aid, and connect individuals to case managers and community resources. These strategies balance compassion with economic efficiency, but they lack targeted care for high-risk but still housed persons.

Lowering the national homeless population means not only finding stable housing for those without shelter, but also keeping people from losing their current housing.

A novel Homeless Prevention Call Center program in Chicago offered rent assistance to callers based on an assessment of who’s at high risk for losing housing. Those who received financial assistance were 76% less likely to enter a shelter than those who did not get funding. Each call resulted in savings of around $9,700 per person, the difference between cost of assistance ($10,300) and benefits ($20,000).

So why is focusing on at-risk groups so difficult? Being unhoused is a statistically rare outcome among people living in poverty and is often difficult to predict based on limited data from medical records and criminal histories. Self-stigma and distrust of housing services also make direct outreach challenging

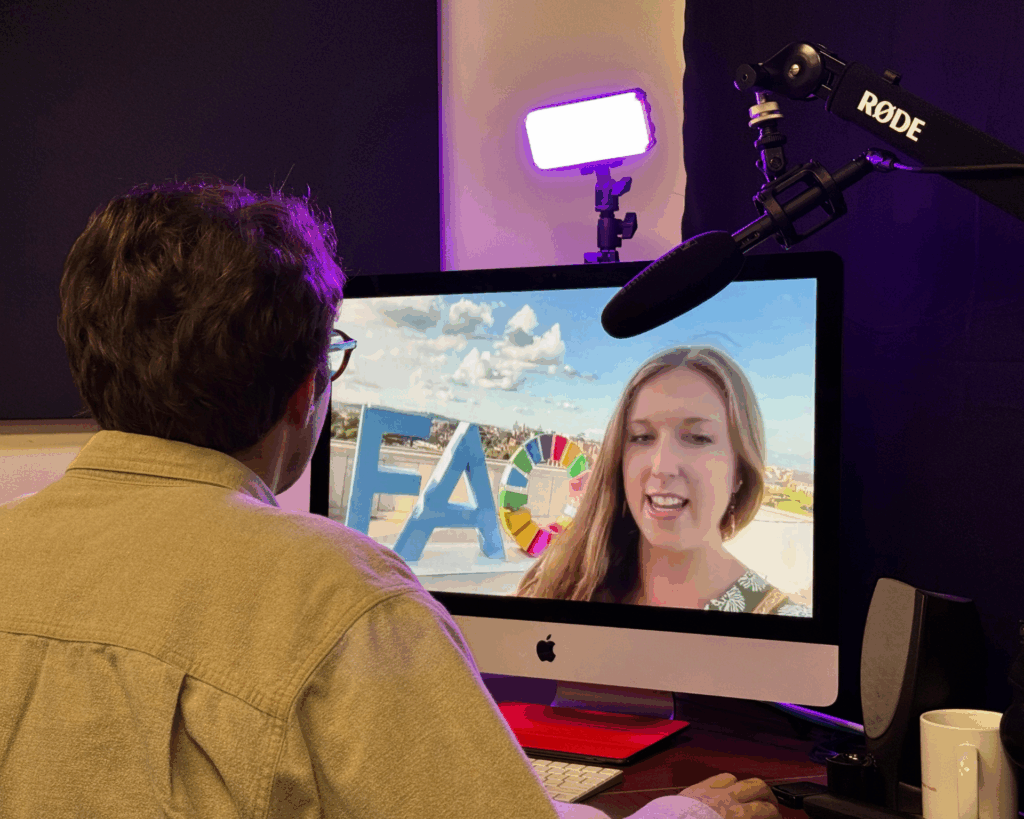

Research teams are working toward more proactive efforts to predict and identify at-risk individuals in more targeted ways. Janey Roundtree and her team at UCLA’s California Policy Lab used machine learning (AI) technology to rate a list of 90,000 individuals for who were at greatest risk of becoming homeless. Researchers used data from seven service agencies across Los Angeles County (e.g., health services, food aid programs, arrest records) to produce a list of highest-risk households. Case managers then cold-called these individuals to offer a portion of the program’s funding from the American Rescue Plan to help with housing stability.

Colin Middleton and his team at Eastern Washington University examined financial health information as a way to predict homelessness. They created a predictive model of homelessness based on monthly utility payment history (i.e. gas, electricity, water) using widely available customer billing records data. The model predicted first-time homelessness within one year for 86.2% of all documented cases. The study calls for pairing utility payment data with other relevant sources to build sophisticated models of care and accurately identify those most at risk.

Lowering the national homeless population means not only finding stable housing for those without shelter, but also keeping people from losing their current housing. Finding ways to make use of a person’s unpaid bills and offering help based on this marker of risk may be a way to identify those who are unseen and perhaps unsure of when they might lose their homes, and help them figure out how to remedy this precarity.