When We Talk About Public Health

According to a new study, there was little discussion by candidates Trump and Clinton of “public health issues” during the 2016 Presidential campaign.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

When We Talk About Public Health

According to a new study, there was little discussion by candidates Trump and Clinton of “public health issues” during the 2016 Presidential campaign.

Combing the texts of major campaign speeches, interviews, and advertisements made by candidates Trump and Clinton for keywords, the authors of this study conclude, “the two candidates did not communicate the major concerns of the public health field.” They bemoan that general references to “health” accounted for less than 1% of the words used by these candidates.

Where it gets interesting is what the authors of the study consider to be “health topics.” The study focused on six “public health issues”: wellness and diet, disease prevention, substance abuse, workplace standards, and vaccinations.

We do not disagree that these are “public health issues.” We suggest, however, that it would be a shame if this short list is what constitutes our political discourse on the issues of public health.

The papers that we summarize each week in the Noteworthy section of this newsletter emerge from a curated catalog of twelve topics—housing, health gaps, immigration, aging, mental health and substance use, military medicine, the environment, criminal justice, food policy, health technology, disability/injury, and health care delivery. We created this list because we think that these areas capture the forces that both shape health and create the state of health that matters to the public’s health today.

We would bet that politicians and the public already spend more than 1% of their words touching on some aspect of these twelve topics. For instance, immigration and military issues dominate popular attention at the moment. But the public health implications of these issues are rarely addressed. For example, we talk about putting undocumented immigrants in detention centers, but what happens when we do not screen for and treat tuberculosis among these immigrants? We talk military budgets, but we don’t talk about the costs of post-traumatic stress disorder (only one of the many hidden health costs of war) to the single-payer insurance system that our military uses.

If there is a unifying idea left in our divided America it is that we all want to be healthier. The public’s health affects everyone. We all share in the benefits of a healthier populace. The public’s health should drive our policies and our political discourse. Every budget, every piece of policy, could be written with a public health implication in mind, if we had the political will.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

BEYOND POVERTY

More than half of all families with children in New York City experience disadvantage. The term “disadvantage” is more inclusive than “poverty” and includes difficulties with housing, running out of food, or having a parent in poor health. The share of families experiencing such hardship is twice as high as the share who experience low income alone. Initiatives that include emergency food assistance, eviction prevention, and respite care for caregivers, as well as navigator-type services that connect families with existing community resources could help with hardship that extends beyond low income.

ON THE MOVE

Older adults are often limited by difficulty walking, and community-based exercise programs for persons over 65 are increasingly common. On the Move, a group-based exercise program for ambulatory adults (50 minutes twice a week) included training in stepping and muscle coordination, and when compared to a program limited to seated strength and flexibility training, improved walking distance. Such preventive, voluntary programs that emphasize the elements of actual walking provide greater independence for persons residing in senior apartment complexes and independent living facilities, or attending community centers.

THE COST OF SEX

Partner notification—the finding, testing, and treating that follows a new reported case of HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia—takes considerable time and effort by state and local health departments. New York State employs 75 disease investigation specialists to cover the 57 counties outside of New York City, but investigates only 25% of cases because of the labor intensity of such work. Nearly all HIV cases (711) were investigated in 2014, but only one in six chlamydia cases were pursued. The cost-per-partner notification was $20,000 for HIV and $2500 for chlamydia, yet a greater proportion of total spending (79 percent) was devoted to gonorrhea and chlamydial investigations because of the greater frequency of these infections. This analysis can help public health departments improve program efficiency and target cost-effective strategies.

WORKING LONGER IN WORSE HEALTH

An idyllic retirement in warm Florida is becoming increasingly unrealistic for many Americans. Nearly 19% of Americans over the age of 65 were working at least part-time in 2017. This was a larger proportion than at any point since American retirees won better health care and Social Security benefits in the late 1960s.

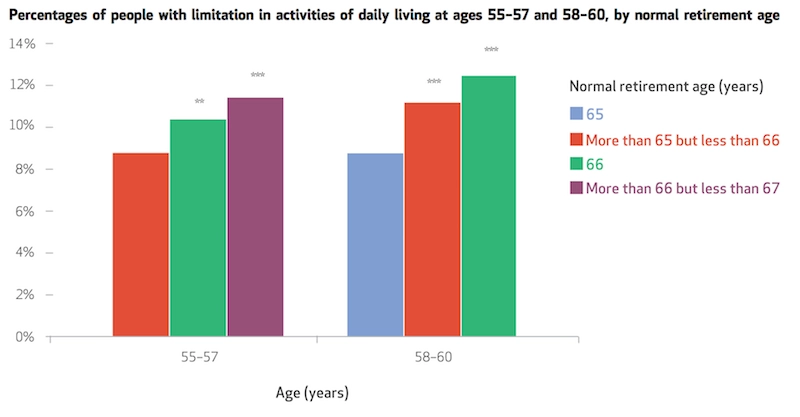

Americans are working longer for greater financial security, presumably so that their retirements are more comfortable. However, recent research published in Health Affairs by Dr. HwaJung Choi and Dr. Robert Schoeni indicates that Americans who work longer to reach Social Security retirement age have worse health.

Dr. Choi and Dr. Schoeni use activities of daily living (ADLs) as an indicator of health. ADL limitation would be classified as having difficulties performing at least one of the following tasks: “walking across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, and transferring in and out of bed.”

The normal retirement age, for the purposes of this study, is the age at which individuals can claim Social Security. New legislation in 1983 moved the retirement age back gradually for the subsequent age groups, or cohorts, in order to account for longer life expectancies and preserve the solvency of the Social Security program. For example, the normal retirement age for those born in 1937 or earlier is 65 years. The normal retirement age for the cohort born between 1943 and 1954 is 66 years, and so on. ADL limitations were examined for the different cohorts.

Even when controlling for education, all cohorts with higher normal retirement ages had higher rates of ADL limitation. Additionally, they found that cohorts with higher normal retirement age had higher rates of poor cognition in comparison to the cohort with the lowest normal retirement age.

Americans are working longer and in worse health even before they reach their respective retirement age. This study supports other research that suggests the health of Americans in their 50s and 60s has worsened over the past two decades. The consequence is “an increase in the share of workers in their fifties and sixties who are in poor health, which will create significant challenges for them and their employers.”

Graphic from “Health Of Americans Who Must Work Longer To Reach Social Security Retirement Age,” HwaJung Choi and Robert F. Schoeni, HEALTH AFFAIRS 36, NO. 10 (2017): 1815–1819 © 2017 Project HOPE— The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0217