As Midterm Elections Approach, Three Steps to Creating a Healthier World

We have argued often in this column that health is the product of the social, economic, and political forces around us, frequently invisible unless we pay close attention to how they influence health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

As Midterm Elections Approach, Three Steps to Creating a Healthier World

We have argued often in this column that health is the product of the social, economic, and political forces around us, frequently invisible unless we pay close attention to how they influence health. The challenge of addressing these forces is one of abstraction. We realize that it is more tangible to say “we need to build more hospitals to make our health better” than to say “we need to ensure that the political environment creates more health.” And yet, the latter is critical and as we head to the midterms we offer a simple three-part prescription for how we can improve health that is so inextricably linked to the world around us.

1. Governance for health

If the conditions of the world around us create health, then we must make sure that health is borne in mind in all decisions made by the political actors who dictate these conditions. This means, for example, that governments need to recognize transgender equity is a sine qua non of health among the transgender community, that punitive incarceration policies undermine the health of minority communities, and that investments in cleaner environments reduce disease in all of us. We should vote for the candidates who will prioritize health in all its forms.

2. Cross-sectoral action that promotes health

Health is created only in part by the public sector. The food we eat comes from the private sector, as do the cars we drive, and the consumer products we use on a daily basis. The private sector influences what we eat, breathe, and drink, and how we behave. We should endorse corporate action that promotes health, directly through choosing to invest in companies that are pro-health, and indirectly through public sector policies that incentivize pro-health corporate action.

3. Demand for health

Ultimately none of the above will be possible without a population-level demand for both public and private sector actions that promote health. The history of this country is full of examples where shifting public demand created health, from the introduction of Medicare, to Obamacare, to demand for mental health parity in insurance payments, gender wage equity, and marriage equality. Ultimately, making health a priority will require a full-throated demand. And this is where, of course, elections come in.

Perhaps these midterms are an opportunity to take a step in this direction.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

BREWS CONTROL

Underage drinkers obtain alcohol from many sources, including friends, siblings, parents, and other adults. This survey study of 15 to 19-year-olds asked, “The last time you drank alcohol, how did you get it?” followed by questions about drinking frequency, troubles, and loss of control. The authors determined that youth who receive alcohol from parents report fewer alcohol-related harms than those who obtain their alcohol from friends, despite no observed differences in drinking frequency. The authors speculate that the effect of parental supply is influenced by the nature and quality of the relationship between the child and the parents. For example, drinking under supervision, parental modeling of safe use, and help with avoiding risky situations (like driving), may contribute to controlled drinking. Just under one-quarter of drinkers report that they obtained alcohol from a parent, guardian, or other adult family member the last time they drank. Parents may help to minimize experiences of alcohol-related harm among youth beyond the simple promotion of abstinence.

RAISING UP LOW-INCOME CHILDREN

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is one of the largest cash-transfer programs in the United States. The EITC distributes over $66 billion to 28 million low-income families and lifts more than three million children out of poverty per year. Since there are no limits on the number of years that households can claim the EITC, this program can affect children from birth until college. However, little is known about the long-term effects of the EITC on children’s outcomes once they reach adulthood. These authors demonstrate the benefits of $1000 per year from EITC when a child is 13-18 years old. Children are 1.3% more likely to complete high school and 4.2% more likely to complete college. Young adults are 1.0% more likely to be employed, with a 2.2% increase in earnings. In addition to the positive economic impacts on its adult recipients, the cash-on-hand provided by EITC also helps children growing up in low-income households during the teenage years, and these effects persist into adulthood.

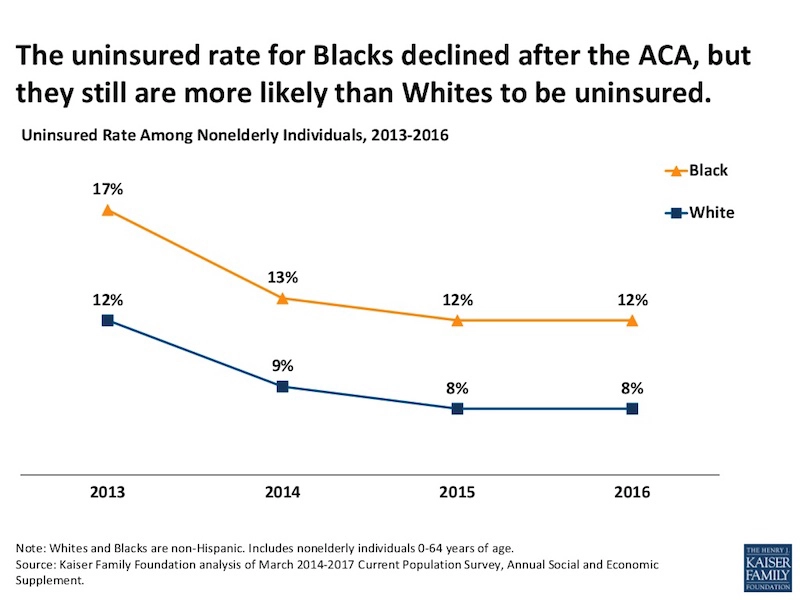

HEALTH INSURANCE DISPARITIES PERSIST AFTER ACA

When the Affordable Care Act passed the Senate in 2009, then-Majority Leader Harry Reid from Nevada said, “Those fortunate enough to have health insurance will be able to keep theirs, and those who do not will be able to have health insurance.” Though the percentage of those without insurance has decreased (as shown in the figure above), Black Americans are still more likely to be uninsured than White Americans.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) used the Current Population Survey from the United States Census Bureau to analyze the differences in uninsured rates between White and Black populations. Those included in the data are non-Hispanic and under the age of 64.

Despite gains in coverage for both White and Black individuals between 2013 and 2016, the uninsured rate for Black individuals remained higher than the uninsured rate for White individuals in 2016. Black individuals make up 15% or more of the population in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. None of these states have expanded Medicaid. The expansion of Medicaid in southeastern states could close the gap in uninsured rates between Black and White Americans. —Chrissy Packtor, PHP Fellow

Graphic from KFF.org, Health and Health Care for Blacks in the United States, Published: January 31, 2018