No Place to Live

Courts across the United States have begun to question the constitutionality of residency restriction laws for sex offenders.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

“No more victims – no one is disposable.” That is the motto of a major restorative justice organization (The Circles of Support and Accountability Canada), emphasizing the importance of both supporting sex offenders and holding them accountable.

Courts across the United States have begun to question the constitutionality of residency restriction laws for sex offenders. Policymakers focused on developing and evaluating policies on sex offenders should incorporate this framework of balancing support and accountability.

Residency Restriction Laws

At least 30 states and several cities have implemented residency restriction laws. These laws typically delineate the distance sex offenders must maintain from places that children can be found such as schools, daycare, parks, and playgrounds. Some laws even include a prohibition on loitering in certain zones. In Milwaukee, WI for example, Mayor Tom Barrett passed sex offender ordinance in July of 2014. The ordinance prohibited sex offenders from establishing “a permanent residence or temporary residence within 2,000 feet or any school, licensed day care center, park, recreation trail, playground or any other place designed by the city as a place where children are known to congregate.” The resulting map of Milwaukee shows that sex offenders are essentially banned from living in the city.

Purpose of These Laws

These residency restriction laws are intended to protect public safety and welfare. As Keri Burchfield pointed out in her 2011 essay in Criminology and Public Policy, however, these policies are implemented “in response to political motivations, perceived public outcry, and misinformation about the true threats posed by sex offenders…”

These laws are also based on the assumption that children are in great danger of an unknown attacker. However, statistics show that relatively few child sexual abuse cases (10%) are perpetrated by strangers. Most of the residency laws are crafted in protection of children, selecting restricted areas based on areas that children frequent. These laws also assume that sex offenders choose their victims based on proximity, which is unsupported by research. While society’s fear of sexual abuse of children is warranted, perhaps keeping unknown sex offenders away from certain areas may not be the most effective preventive measure.

Another public perception of sex offenders is that they are highly likely to re-offend. However, the rate of recidivism for sexual crimes remains low at 5.2% after three years. Different types of sex offenders have varying rates of recidivism for different offenses but the law places all sex offenders in the same category, creating barriers that make it hard for many people to lead a productive life.

There is a wide variety of offenses that would qualify a person to register as a sex offender. In some states, offenses that are not strictly related to sexual abuse and involve little violence can qualify a person for the sex offender registry. Public urination, consensual sex between teenagers, and public indecent exposure can be reason enough in many states. In many cases, acts committed by children result in their names being added to the registry and this status following them as they move into adulthood. Eighteen states require a mandatory lifetime registration period for all sex offenses, regardless of the severity of the charge. Other states have a tiered system for determining the length of time someone must remain registered.

Consequences of Residence Restriction Laws

Research suggests that these laws do not improve public safety. According to a study in 2009, there are three crucial components that can reduce the rates of sexual recidivism: housing, employment, and social support. All three components are intertwined. The inability to live with family or friends can deprive sex offenders from crucial social support. The lack of employment, often a consequence of their sex offender status, can also drive the inability to find affordable housing.

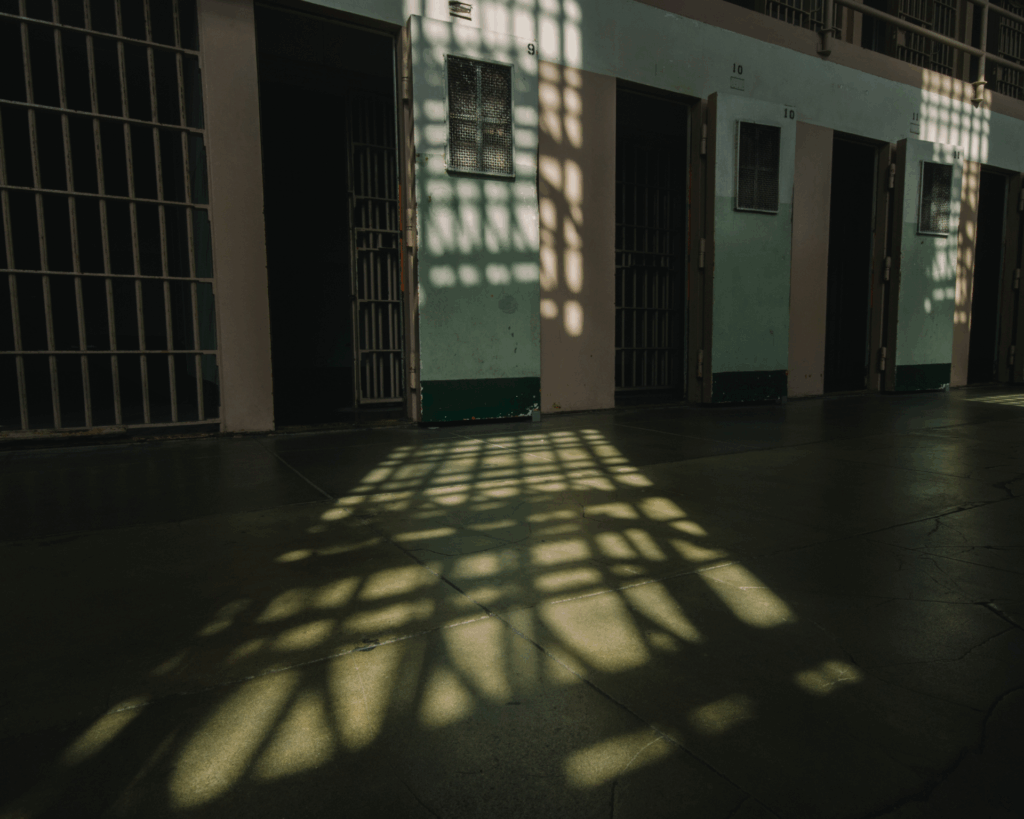

Often, they end up homeless, meaning they are not technically in violation of the law but are untraceable, defeating the purpose of policies meant to keep them away from certain areas. For example, in a study of 109 sex offenders in Broward Country in Florida, 39% of sex offenders experienced homelessness or had to live with someone for two or more days. The number of sex offenders experiencing homelessness in Milwaukee increased from 16 to 205 after the passage of the residence restriction laws. As a result, these laws cause stress, alienation from society, and hopelessness, all of which can trigger a relapse, re-offending, and re-incarceration.

Keri Burchfield argues that the restrictions create “dumping grounds”, or areas with high concentrations of sex offenders. The law left sex offenders with only 55 addresses inside the acceptable zones. Some landlords of the 55 addresses refused to rent to sex offenders. These laws are often so restrictive that they undermine the very accountability aspect of the law of keeping track of sex offenders. As seen in the map below, many sex offenders may violate the ordinances because they simply have no other options. Residency restriction laws in Buffalo seem to have little effect on the location of residence for the sex offenders.

No One is Disposable – No More Victims

When does society stop punishing offenders even after they serve their time? The residence restriction laws, while rooted in good intentions to protect public safety, accomplish little in preventing recidivism. The laws are driven by public assumptions and generalizations about sex offenders instead of being grounded on evidence. Societal alienation produced by restrictive practices can lead to higher rates of recidivism.

Residence restriction policies should be revisited. California has recognized the issues with Jessica’s Laws, which was their version of the residency restriction laws, and revised them in 2015. The revisions largely removed the blanket restrictions, but left them intact for only high-risk sex offenders and anyone with offenses involving children under 14 years old. However, most other states still have blanket residency restrictions. Instead of reliance on restrictions, the emphasis should be on rehabilitation and reintegration programs that will assist with housing, employment, and social supports. The law must move away from the one-size-fits-all model that places all sex offenders into one category even though research shows that different types have varying risks upon release. Better reintegration programs, tailored to the unique needs of sex offenders, will likely lead to safer communities.

Feature image: Kevin Spencer, To Offend, used under CC BY-NC 2.0/cropped from the original

Milwaukee map from City of Milwaukee Public Notice

Buffalo map from A Geospatial Analysis of the Impact of Sex Offender Residency Restrictions in Two New York Counties, Jacqueline A. Berenson and Paul S. Appelbaum