It’s the Crash, Dummy

Persistent injury disparities between the sexes proves that prioritizing men in vehicle safety creates life-threatening consequences for female drivers.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

Motor vehicle safety is heralded as one of the 10 most important public health achievements of the 20th century. Advancements in car safety do not, however, equally benefit everyone.

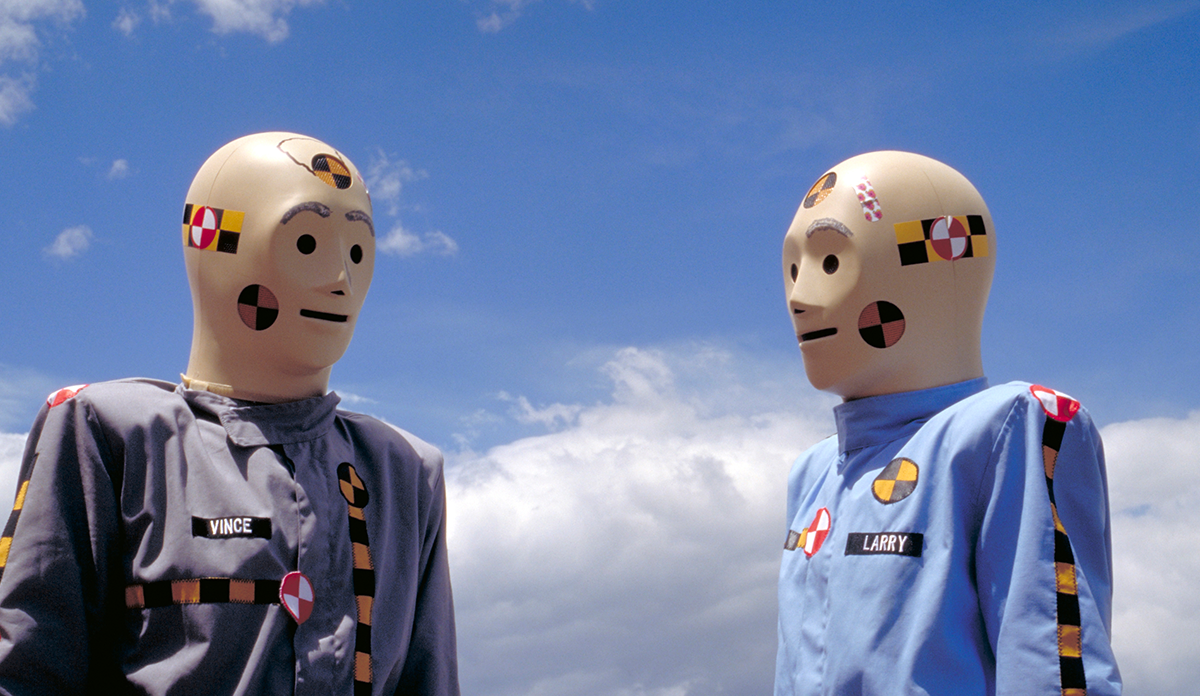

The first crash test dummy was created in 1971. The model was built to represent the average adult male. A female dummy wasn’t developed and used in safety testing in the US until forty-one years later in 2012. But the female model is closer in size to the average 12- or 13-year-old girl than an adult woman and for that reason is more often tested in the back or passenger seat than in the driver’s seat.

The female crash dummy is less than five feet tall and weighs only 108 pounds. The average adult female is closer to five feet and three inches. Male dummies, on the other hand, come in two adult sizes: the average male dummy and a large male dummy.

Being entirely excluded from safety testing for decades has affected how severely women are injured during car accidents. The vulnerability of female drivers was first brought to attention in 2011 when researchers at the University of Virginia discovered that women had an almost 50% higher risk of serious injury than men.

The evidence warrants inclusion of appropriate female models in all testing so that safety-rated vehicles are, in fact, safe for everyone.

Almost 10 years later, the University of Virginia research group again looked at gender disparities in injury severity. Since the 2011 study, new regulations have been enforced requiring use of the small female models in some safety testing. Despite this advancement, researchers found the increased risk for female drivers has not improved. Even when wearing a seatbelt, female drivers are still at higher risk for almost every type of serious injury. The disparity is significant for all age groups and persists no matter the driver’s height, the driver’s body mass index, the age of the vehicle, or the severity of the crash.

Prejudice against female drivers continues to exist, as do attempts to blame their driving behavior for the severity of their injuries. However, studies have found that men engage in risky driving behavior more than women. Women also wear seatbelts more often than men.

Women differ from men in more than just height and weight. Sex differences in mass distribution and anatomical structure, such as torso shape and spine curvature, affect how resilient a human body is to injury during a car accident. Seatbelts and airbags created to protect the average male form do not fit the average female body the same way and, therefore, do not protect women equally.

Additionally, a pregnant dummy has never existed. Volvo recently created a virtual pregnant dummy for use in safety test simulations, but so far no other manufacturer is required to test with it. Meanwhile, car accidents remain the leading cause of death in pregnant women and loss of pregnancy due to trauma.

When regulations first expanded to include the small female dummy, multiple car manufacturers complained that the new requirement was burdensome and unnecessary. They argued the male dummy was representative enough for the entire adult population. Persistent injury disparities between the sexes proves that prioritizing men in vehicle safety creates life-threatening consequences for female drivers. The evidence warrants inclusion of appropriate female models in all testing so that safety-rated vehicles are, in fact, safe for everyone.

Photo via Getty Images. Visualization by Tasha McAbee.