Income Inequality and Our Health

Pre-tax incomes for the poorest 50 percent of Americans have stayed mostly unchanged for the past 40 years. As our economy has grown, the pre-tax share of national income among the poor has dropped significantly, widening income gaps in the country.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Income Inequality and Our Health

Pre-tax incomes for the poorest 50 percent of Americans have stayed mostly unchanged for the past 40 years. As our economy has grown, the pre-tax share of national income among the poor has dropped significantly, widening income gaps in the country. We leave the question of why inequality matters for the economy to others. What is of concern to us is whether income inequality matters to our health and to the extent that it does, how we in the health profession should respond.

Twenty-five years ago, Richard Wilkinson, then a professor at the University of Sussex, published a paper in the British Medical Journal called “Income distribution and life expectancy.” The paper concerned twelve European countries and concluded that “the relation between income distribution and life expectancy is sufficiently strong to produce significant associations.” The paper’s provocative thesis launched two decades of intense scientific discussion about the role of national income inequality in producing health (and death), including several systematic reviews, and books. This work, which continues to the present day, shows that income inequality is a foundational driver of physical and mental health. By way of example, a systematic review published just this February considers the relationship between income inequality and depression and concludes that across studies there is “greater risk of depression in populations with higher income inequality relative to populations with lower inequality.”

Why might income inequality affect the health of the public?

Countries or regions where there are wide gaps in income are characterized by weaker social ties and less investment in the social and physical resources that create health. Countries with more income inequality are less likely to have healthy air, water, food, safe places to work and play, and affordable quality housing—all of which create health.

We are convinced then that income inequality should indeed be the remit of public health professionals. Embracing this, the authors of the systematic review of depression conclude that “policy makers should actively promote actions to reduce income inequality, such as progressive taxation policies and a basic universal income. Mental health professionals should champion such policies.”

Does entering the conversation on taxation policies, the minimum wage, and universal income guarantees stretch the bounds of what most of us expect to be the topics of public health?

Unquestionably it does. But we believe that such stretches should be our new purview. After all, as recently as eighty years ago few imagined that cigarettes had anything to do with health, and doctors promoted cigarettes. It was a stretch of our collective imagination then to see health tackling smoking and the tobacco industry, as much as it is now to see addressing income inequality as part of our work. But the evidence suggests that they both matter to our public health. With the responsibility of witnesses, we should speak up, with a careful eye on new data and humility about which policies to “champion” when considering large issues like income inequality.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

THE LASTING EFFECTS OF INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

Intimate partner violence (IPV)—physical, sexual, or psychological aggression—has a lasting impact on affected women. Women who have lived in a violent relationship have higher rates of bodily pain, depression, suicide attempts, and PTSD compared to women who have not, and these health effects of violence against women often persist for decades.

READING, WRITING, AND VACCINATION

Maine, 2009: a flu pandemic is underway. State and education authorities decide to have all K-12 schools in the state offer vaccination clinics. The resulting 25% increase in vaccinations of Maine children was extrapolated by the authors to determine the effectiveness of this policy in preventing flu-related illness across Maine’s population. The conclusion: school-based flu shot clinics can be a cost-effective way of vaccinating children who are typically under-immunized. If vaccine supplies are limited, however, such clinics reduce availability for adults, and may put the elderly at risk. The allocation of vaccine during a mass immunization depends on decisions regarding targeted age groups, infection risks, and potential venues for delivering protection rapidly.

WHEN DOCTORS RESPOND TO GUIDELINES

In 2009, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggested that cervical cancer screening for women before the age of 21 was no longer required. This study of 18 to 20-year-old women in the Tennessee Medicaid program showed a 73% decline in Pap tests over the next five years in response to guidelines, and a parallel decrease in the frequency of unnecessary and potentially harmful colposcopies and invasive cervical procedures. Costs also fell more than $100 per woman. HPV vaccine remains the preferred way to prevent cervical cancer. Young women who no longer receive a Pap test for cervical cancer may still need testing for other STDs such as chlamydia, and should be vaccinated against HPV if they weren’t as adolescents.

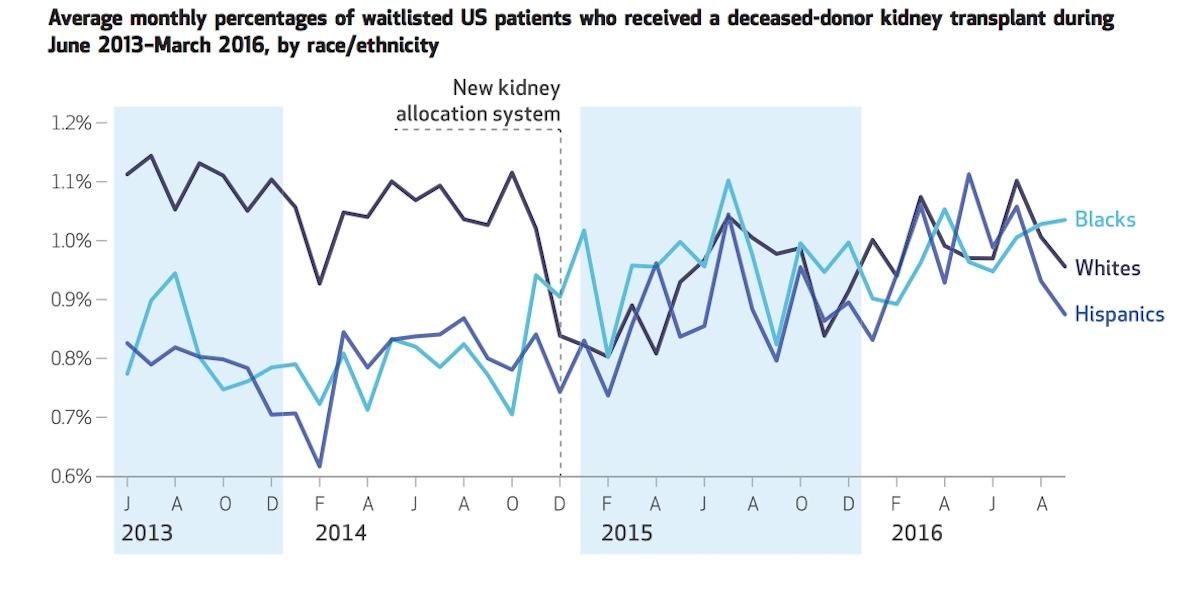

RACIAL EQUITY IN TRANSPLANTS

Stark disparities exist between the health outcomes of white people and minorities across a wide range of health indicators. One prime example is organ transplant allocation. Prior to 2015, kidney transplants for those with end-stage renal disease went to white patients at a much higher rate. A new allocation system was devised in order to change that. The simple yet ingenious solution attacked the structural cause for the inequity. It kept time on the donation list as the main selection criteria, but the fix by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) acknowledged that because of underlying healthcare disparities, black and Hispanic people spend more time on dialysis before being put on the list. The new system places the starting point at the earliest date a patient was either put on the list or started regular dialysis treatments. Melanson et al. show in their Health Affairs article that the new UNOS system worked as intended and that the disparities have been largely addressed.

“New Kidney Allocation System Associated With Increased Rates Of Transplants Among Black And Hispanic Patients.” Taylor Melanson et al. HEALTH AFFAIRS VOL. 36, NO. 6: PURSUING HEALTH EQUITY. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1625