In Social Media We Trust

We have grown accustomed to social media reading our thoughts. One day we are using Facebook to exchange notes about an upcoming wedding invitation, and the next day Facebook ads highlight discounts on potential wedding gifts.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

In Social Media We Trust

We have grown accustomed to social media reading our thoughts. One day we are using Facebook to exchange notes about an upcoming wedding invitation, and the next day Facebook ads highlight discounts on potential wedding gifts. We post photos of a new item of clothing on Instagram and next we are receiving ads from the newest crop of design stars.

Of course our social media apps are not reading our thoughts—they are reading our photos, shopping patterns, and the actual words we write in our emails and posts. We have come to think of this type of targeted advertising as unremarkable, even as, in recent years, we have become aware of the potential havoc this type of micro-targeting can wreak on our democratic process.

But what if this micro-targeting, instead of being only a force to generate consumer interest, were also a force for good? What if our words offer a means to ameliorate an important public health problem like Americans’ growing suicide rate?

Let’s say that InstaTwitBook had an algorithm that could quite accurately judge that a user was suicidal from changes in the language she communicated online. Let’s say that site administrators could send this person at risk for suicide a gentle message suggesting that she is evincing warning signs of depression, or maybe even nudge her by directing advertisements about local mental health counseling to her without overtly mentioning mood. Let’s say that 3,500 persons could be reliably identified and sent such messages this year and that 1 in 100 would lead to care-seeking and 35 suicides averted. And it’s not just InstaTwitBook that has the power of detection. Phone companies may be able to tell from your voice if you’re depressed, and use that information to identify who may benefit from mental health help.

Are we okay with this company’s public health action, if done not to make money, but for the good of its users? Should InstaTwitBook pursue this public health campaign to save lives in our era of rising suicide deaths?

In some ways we do not see why we should not be in favor of this. After all, we accept intrusion about issues that matter much less than issues of life and death. But we are also not blind to the challenges that arise from this approach. In part, the scale of the challenge depends on the harm of the inevitable inaccuracy, of false-positive results, and the sending of notifications to persons who aren’t suicidal. What if there were unintended consequences; what if depressed persons stayed away from social media, growing more isolated, rather than get singled out?

Answers to these questions would take some research, and to conduct such research will require that social media companies be open to third party investigators using their data. Given the reach of social media, and the potential for good that such efforts can achieve, we think such research is long overdue.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

VENDING SPENDING

Vending machines in the US sell $10 billion of candies and snacks a year. These authors chose highly-used machines at one university, grouped healthier products (marked “Eat Well”) into one eye-level section that accounted for one-third of these machines’ displays, and raised the price of popular candy bars 25%. They compared individual sales and overall financial performance with other unmodified machines on campus. During the two-month intervention period, 21.3% of products purchased from the intervention machines were healthier choices, compared to 1.3% of purchases from comparison machines. Revenue was not compromised compared to the previous year among the intervention machines. Health-promoting interventions can influence consumers who are undecided about what snack to choose when they approach a vending machine.

PSEUDOSCIENCE AND ABORTION POLICY

In 2012, when US Representative Todd Akin from Missouri was asked if abortion was justified in cases of rape, he notoriously said that pregnancy as a result of rape is rare because “the female body has ways to try and shut that whole thing down.” Arguments made against abortion, like this one, are often riddled with pseudoscience.

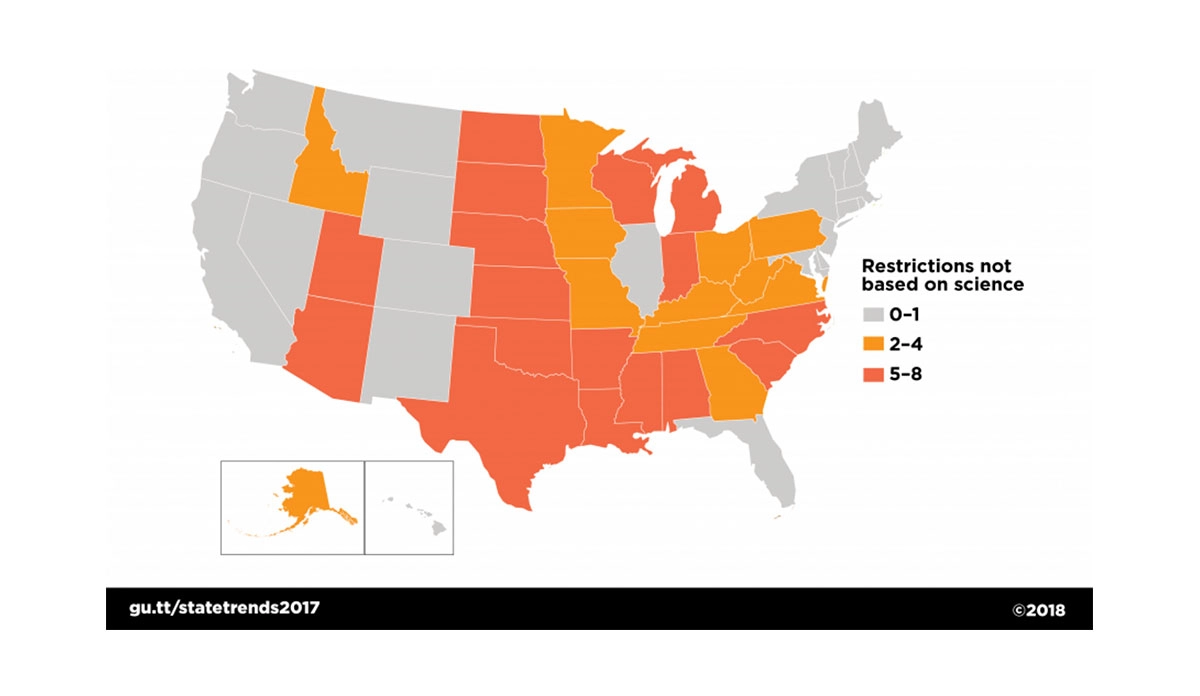

As the map above shows, 29 states, home to 88 million women, have implemented at least two abortion restrictions not backed by scientific evidence.

For example, Texas’s “Woman’s Right to Know” booklet, offered to patients before having an abortion, uses deceptive language to lead readers to believe that abortion increases the risk of breast cancer. The Washington Post’s Fact Checker gave this claim in the booklet three “Pinocchios” on their rating scale, meaning that there was a “significant factual error” present. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released a statement in 2009 concluding that there is “no association between induced abortion and breast cancer.”

Kentucky’s Senate Bill 5, passed in 2017, made it illegal to have an abortion after the twentieth week of pregnancy. The sponsor of the bill cited fetal pain as justification for the law, calling abortion after 20 weeks an “awful painful experience” for the fetus. However, a review of fetal pain evidence found that fetuses are unlikely to feel pain before the third trimester (around 29 weeks).

Kansas, Texas, and South Dakota have the highest number of these types of pseudoscientific restrictions with seven each.

Map: Guttmacher Institute, States Hostile to Abortion Rights, Policy Trends in the States, 2017