The Importance of Medicaid DSH Payments

Steven Heath on why Medicaid DSH provider payments are an important public policy issue as we move through “repeal and replace.”

Read Time: 8 minutes

Published:

Medicaid DSH provider payments are an important public policy issue as we move through “repeal and replace.” Let me tell you why.

Overview

The Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program is an important funding stream for hospitals that treat a large proportion of uninsured, low income, and Medicaid patients. Understanding how this funding stream currently works, how it came to be in its current form, and what reform might look like are crucial if we are to adequately support hospital care for low-income patients. This should be a current concern with the talk of ACA repeal and consideration of potential replacements because changes in legislation directly and indirectly affect the levels and distribution patterns of this critical hospital funding stream.

If the funding stream of Medicaid DSH is reduced, hospitals currently receiving these funds will be negatively impacted by having lower payment-to-cost ratios for Medicaid patients. This could lead to the hospital putting off capital improvements or curtailing services, such as intensive care units or outpatient drug treatment. Conversely, the pressures placed on state governments and hospitals by reductions in Medicaid DSH could result in a more rational distribution of these funds toward hospitals that serve a greater portion of Medicaid and low income patients.

Background

States make DSH payments to hospitals in addition to standard Medicaid payments. DSH payments are considered supplementary to regular Medicaid payments to hospitals. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low-income and uncompensated care patients, whether these patients are Medicaid, uninsured, or otherwise unable to pay, are eligible to receive Medicaid DSH payments. That is, Medicaid DSH payments are intended to improve the financial stability of select hospitals within a state by offsetting uncompensated care costs for Medicaid and uninsured patients and, thus, bring Medicaid payments closer to Medicaid costs.

State DSH payments to hospitals qualify for a federal match at the state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) amount. However, the amount that the federal government pays each state is a fixed amount known as the DSH allotment. The federal share plus the state share is known as the “total computable.” States are not allowed to pay DSH in excess of the total computable.

States may distribute these funds to individual hospitals any way they like, however, they are required to pass at least a portion of these payments on to hospitals that are deemed DSH hospitals. A deemed DSH hospital is one that has a Medicaid inpatient utilization rate (MIUR) greater than one standard deviation above the state average MIUR and/or a low-income utilization rate (LIUR) that is greater than 25 percent.

Medicaid DSH began in FY 1981 after Medicaid payments to hospitals were uncoupled from Medicare payments. This decoupling led to concerns that hospitals serving a large proportion of Medicaid/low-income/uninsured patients might find themselves under financial strain. Initially, no limits were placed on how much DSH funding states could allocate to hospitals in their state and since a match from the Federal government was forthcoming, there was a significant incentive for growth in Medicaid DSH spending.

An additional factor in the growth of Medicaid DSH payments was that states adopted provider taxes and assessments to increase their federal matching funds. Federal policy, initiated in 1987 (Matherlee 2002), stipulated that money that was taken from providers as a “tax” or “assessment” could be given back to providers and the states would get the Federal matching funds on these reallocated tax dollars. These Federal funds were essentially “free” money to the states that implemented provider taxes.

The combination of a lack of limits on DSH payments and the ability to raise federal dollars through the FMAP match created significant and rapid growth in DSH spending. DSH expenditures rose from $1.3 billion in FY 1990 to a high of $17.7 billion in FY 1992 (Holahan et al. 1998).

To counter this trend, Federal DSH payments were capped with a Federal allotment. Allotments were initially established for FY 1993 and are statutorily defined. Generally, each state’s allotment is based on its FY 1992 DSH spending (P.L. 102-234). This law also sets the ceiling for the amount of DSH funds each hospital may receive at the amount of uncompensated care (UCC) each hospital incurs. This allotment process is historically based and does not reflect any attempt to distribute DSH allotments to states in the most need.

Analysis

In an effort to understand the relationship between Medicaid DSH payments and the levels of Medicaid and UCC in each hospital, Congress added a statutory requirement in 2003 that states submit an annual financial report for each hospital and acquire an independently certified audit of its DSH payments. The report must include data on the MIUR, LIUR and uncompensated care as well as total DSH payments, total Medicaid payments, and payments for the uninsured. This is the only data available to conduct analyses of the Medicaid DSH program. Data on uncompensated care are also reported on worksheet S-10 of the Medicare Cost Reports (MCR), however these data are inconsistently reported between hospitals and the MCR are designed to collect information on Medicare, not Medicaid.

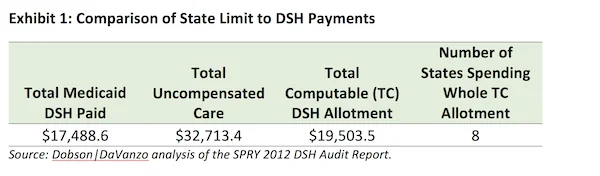

Plans to reform Medicaid DSH program typically start with the program’s current spending in each state. This is because the implementation of a system which radically changes the existing Medicaid DSH payment structure could be traumatic to states that see large decreases in Medicaid DSH payments, however, there are some ways to start reforming the system that would decrease payments with minimal disruption. For example, some states do not utilize the total amount of Medicaid DSH that is available to them under the Medicaid DSH limit, the sum of uncompensated care in all the hospitals in each state. See Exhibit 1.

This represents nearly half (46%) of total uncompensated care expenditures for which states are not being reimbursed. States are, however, using 89% of total computable (state plus federal match) allotments.

Congress called for reductions in Medicaid DSH payment in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in anticipation of decreased uncompensated care associated with Medicaid expansion and enrollment under the ACA marketplaces. To distribute Medicaid DSH payments cuts at the state level, CMS devised a strategy called the DSH health reform methodology (DHRM).

DSH reductions have been delayed by Congress multiple times and are currently scheduled to begin in FY 2018. The possible repeal and replacement of ACA has led to renewed calls for a delay in the enactment of DHRM or outright repeal.

However, the DHRM has the potential to better rationalize Medicaid DSH payments by directing those payments to those states that have relatively high levels of Medicaid utilization and UCC. The methodology utilized by DHRM to reduce and reallocate Medicaid DSH payments involves using the:

1. Current allotment;

2. Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP);

3. Uninsured rate;

4. Medicaid Inpatient Utilization Rate (MIUR); and

5. Uncompensated care (UCC) level.

The distribution of Medicaid DSH in the DHRM is dependent on the interplay between the MIUR, the UCC level and the uninsured rate. Medicaid expansion muddies the water because it expands the MIUR but reduces the UCC level and the uninsured rate.

We modeled the DHRM and alternatives that would reward states that target their DSH money to hospitals with high MIUR and UCC levels. This involved allowing each state to fully fund high MIUR and/or UCC hospitals up to their total UCC level. DSH payment reductions would affect those hospitals that have lower MIUR and/or UCC and this in turn would change the distribution of the DSH allotment reductions among the states and different hospital types.

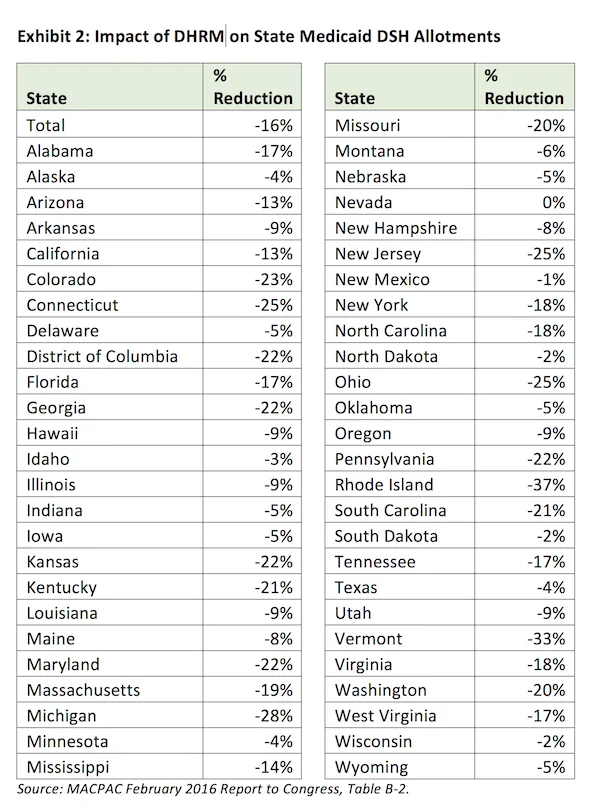

DHRM modeling better targets Medicaid DSH at the state level, but leaves open the question as to how states actually distribute their overall allotment to hospitals within their borders. It is very difficult to model how states would approach this problem. Exhibit 2, taken from the MACPAC February 2016 Report to Congress, shows how DHRM might change Medicaid DSH allotments across states under the DHRM.

It is important to note that even if further health reform results in no reduction in Medicaid DSH, the DHRM offers a model of how to better allocate DSH allotments.

Given that the DHRM rationalizes the federal Medicaid DSH allotment to states, it is reasonable to keep some form of the DHRM under repeal and replace. This would make Medicaid payments to hospitals more equitable in a future world with or without the ACA.

Feature image: Cynthia Cheney, 314/365 — 11/10/2011. Waiting. There’s a lot of that at the hospital. Used under CC BY-NC 2.0 license/cropped and color adjusted from original.