Immigration and the Health of the Public

Maximizing the health of immigrants can increase the health of society as a whole, per Michael Stein and Sandro Galea in The Public's Health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Immigration and the Health of the Public

Throughout his political career, the current President has defined himself in large part by his antipathy towards immigrants; from his disparaging remarks about Mexican immigrants (and judges) at the start of his presidential campaign, to his administration’s ban on immigrants from several majority-Muslim countries. Leaving aside the callousness of such statements and actions, they have drowned out a conversation that we should be having about the health of immigrants.

Immigration is neither a new issue, nor an exclusively local one. In 2017, there were more than 250 million immigrants living worldwide, and about 2.4 million migrate across national borders each year. It is estimated that more than 750 million people live within their country of birth but in a different region, having migrated within national borders. Economic, political, and social forces drive migration. Migrants who are forced to leave their country due to war or persecution become refugees; there were 65 million refugees worldwide at the end of 2017.

The migration experience itself affects health, particularly for vulnerable populations, but the “healthy immigrant” effect suggests that those who are healthier immigrate in the first place—migration after all is an arduous process. More importantly from the point of view of a host country, conditions experienced by migrants in their new countries are strongly determinative of health. For instance, legal status in the host country is associated with access to a broad range of health services and resultant better health. A study in Denmark found that refugees were disadvantaged in terms of some cardiovascular disease outcomes and equal or better off than a Danish-born comparison group in others, but family-reunified immigrants had significantly lower incidence of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and myocardial infarction across the board.

Aggressive anti-immigration tactics are notably unhealthy. Policies at our borders traumatize families and mental health care is the greatest unmet health need. In-country, there are spillover effects. Federal raids can affect the birth-weight of babies born to US-born Latina women following immigration authority raids in search of undocumented Latinos.

Creating the conditions for immigrants to stay healthy helps us all. A recent measles outbreak in Minnesota was fueled by low vaccination rates in refugees who often mistrust providers and fear discrimination and deportation. Rather than shouting about the imagined evils of immigration, we should be doing all we can as a country to maximize healthy immigrants.

Contrary to the current administration’s narrative, migrants are not trying to take resources away from Americans—they are simply trying to create a life for themselves and their children that was not possible at home. Study after study shows that immigrants increase productivity. We should be celebrating such effort.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

FIGHTING IS FALLING

Adolescents get into fights, and about 150,000 times a year seek medical care for their injuries. These researchers measured self-reported fighting among young people ages 12-17, and they report a 29 percent decrease nationally between 2002 and 2014. Adolescents involved in property and drug crimes, those with school failure and parental conflict, and boys had greater involvement in violence. Racial disparities persist, with Black youths most affected. Still, the fall in fighting aligns with similar declines in substance use among American youth.

MULTI-DOSE VACCINES: NOT GETTING IT DONE

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is a multi-dose series of shots to prevent an infection that already affects almost 80 million people in the United States. HPV can cause many types of cancer, including anal, genital, oral, and throat cancer. Both women and men are at risk of HPV-related cancers.

Researchers from the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health used claims from a database of 1.3 million privately insured individuals to assess the percentage of people receiving the second and third shots in the HPV vaccine series within one year of starting the recommended vaccination schedule. Data from individuals ages 9 to 26 years from 2006 to 2014 were used.

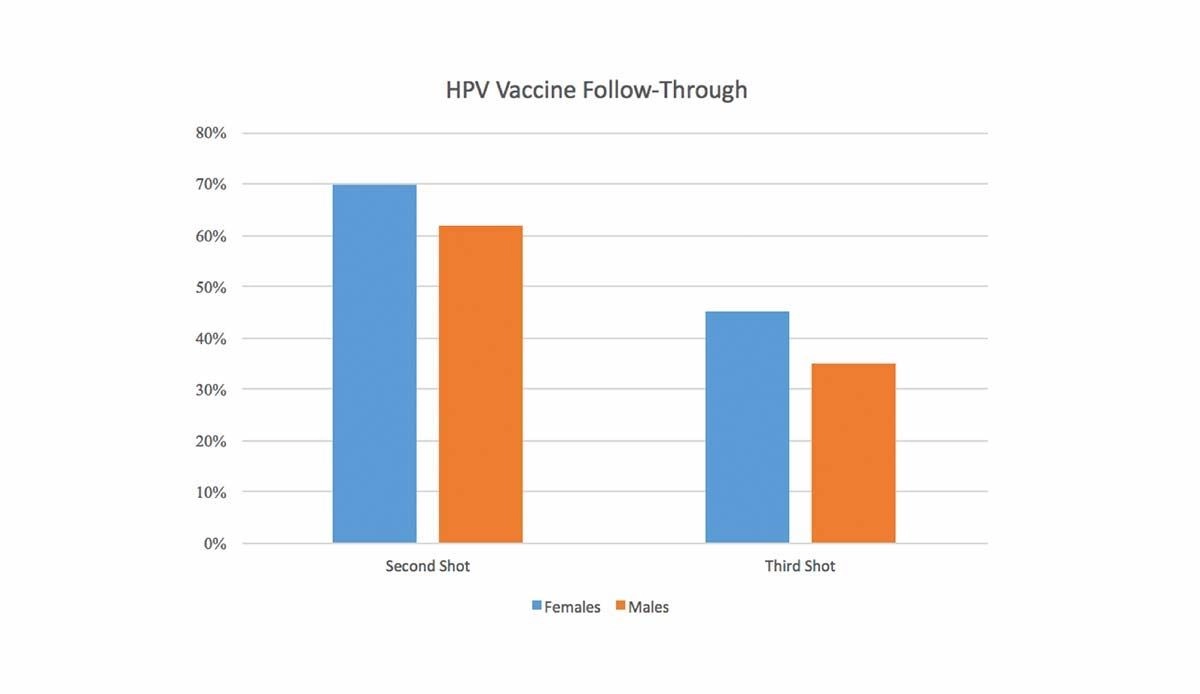

As shown in the graph above, female patients were more likely than male patients to receive both the second and third shots, demonstrating how difficult it is to get young patients (or the parents who transport them) to return for multiple visits of preventive care.

Though this lack of adherence to vaccination protocol looks bad at first glance, it may not have such bad effects. The CDC recommends that adolescents who start the series before their fifteenth birthday receive only a two-dose series; two shots provide adequate protection against HPV infection. But providers and parents need to be on notice that for many adolescents, males in particular, figuring out ways to get this vaccine series administered in full, will not be an easy task.—Chrissy Packtor, PHP Fellow

Feature image by Chrissy Packtor.