How Aid Cuts Threaten Global Health Gains

Recent U.S. funding cuts will likely increase maternal, child, and infant mortality, undermining decades of progress in global health.

Read Time: 4 minutes

Published:

For 64 years, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) provided emergency aid during natural disasters and conflicts, funded health programs, and supported economic development across the globe to promote American interests abroad. All 11 presidents since the agency’s founding by John F. Kennedy in 1961—Democrats and Republicans alike—have supported it. That changed in February, when President Donald Trump cancelled 83% of its foreign aid contracts.

The abrupt and sweeping termination of development aid will have catastrophic consequences for global health. In many countries, the U.S. provided much of the funding for infectious disease management and reproductive and maternal health programs. For example, HIV drugs were once so expensive that the diagnosis was essentially a death sentence in many African countries. But U.S. funding through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which was launched by President George W. Bush in 2003, reduced the price of drugs and has been credited with saving some 26 million lives. Now, an additional 176,000 people will likely die from HIV-related illness in the next year as a result of President Trump’s funding cuts.

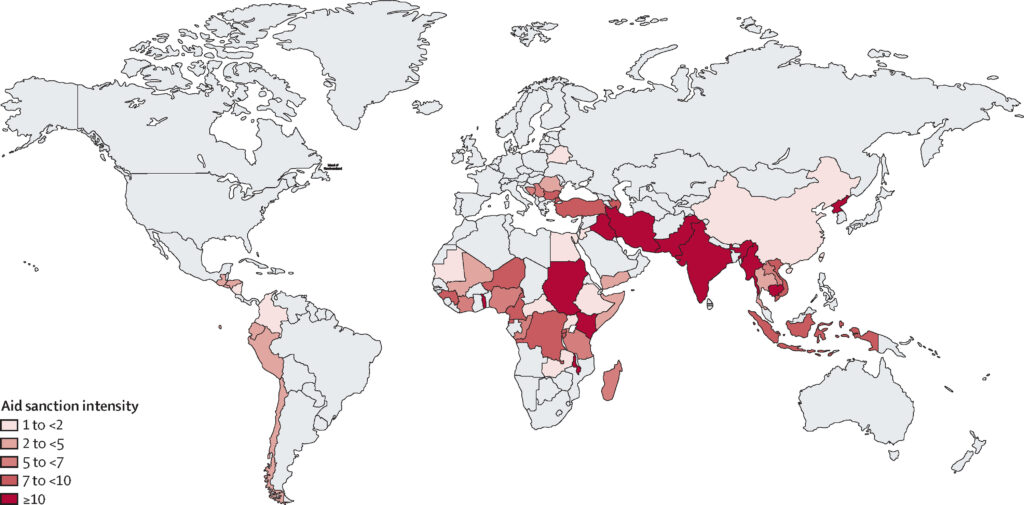

History offers insight into what happens when powerful governments remove funding from vulnerable countries. The changes to USAID are not sanctions, but their effects will likely mirror those of sanctions because they restrict funding for health programs in resource-constrained countries. To understand this impact, Ruth Gibson and colleagues examined data from 67 low- and middle-income countries that were targeted by sanctions between 1990-2019, including Burkina Faso, Sudan, and Myanmar.

Sanctions are a foreign policy tool governments use to put economic or diplomatic pressure on another country. These measures, which can include economic restrictions, trade barriers, or cuts to aid, are often used in response to political coups, armed conflicts, or human rights abuses. They are almost always imposed by powerful nations onto more vulnerable ones, reinforcing global power structures.

[T]his study reveals the human cost of power plays disguised as policy—and reminds us who pays the price when support is pulled.

Over the 29-year study period, the U.S. cut health and development funding to sanctioned countries by an average of $213 million per year. This reduction led to an increase in maternal, child, and infant mortality. Affected countries experienced an additional 47 deaths among children under five each year, and an additional 129 infant deaths and 11 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. These figures represent increases of 3.1% in infant mortality, 3.6% in under-five mortality, and 6.4% in maternal mortality compared to average rates in low- and middle-income countries.

Both historically and currently, the vast majority of maternal and infant deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, but considerable progress has been made in the past decades. Between 2000 and 2023, the global maternal mortality ratio dropped by nearly 40%—from 328 per 100,000 live births to 197. In sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of maternal deaths occur, there were large reductions in maternal mortality over that time (from 748 to 454 deaths per 100,000 live births).

Gibson’s study shows that aid sanctions set this progress back dramatically. A five-year period of sanctions negated up to 30% of the progress made in reducing infant and under-five deaths, and about 60% of progress in reducing maternal deaths achieved over that same five-year period. This would mean roughly 13,800 additional maternal deaths across Africa each year.

Politicians often position sanctions as an alternative to armed conflict, a way to influence geopolitics while keeping civilians safe. And yet, aid sanctions carry profound humanitarian consequences, particularly when they restrict access to medical care among vulnerable populations.

The recent U.S. policy changes are not sanctions, but if history is any indication, they will increase maternal, child, and infant mortality, undermining decades of progress in global health. With political instability on the rise around the world, this study reveals the human cost of power plays disguised as policy—and reminds us who pays the price when support is pulled.