Housing and the Public's Health

Thoughts on improving the health of populations

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Housing and the Public’s Health

Housing is a foundational determinant of health and has been recognized as such since the early days of public health. In the 19th century, outbreaks of infectious diseases sparked interest in housing reform to address poor sanitation, crowding, and inadequate ventilation. One hundred and fifty years later, a report from the WHO commission on the social determinants of health has returned to the concept of “safe housing” as key to the health of populations.

There are ample data connecting poor housing conditions to a broad range of infectious diseases, chronic diseases, injuries, childhood development and nutrition issues, and to mental health. For example, substandard housing conditions such as poor ventilation, pest infestation, and water leaks are directly associated with the development and exacerbation of respiratory diseases, such as asthma. There are about 24 million Americans with asthma, and it is the most common chronic disease in children worldwide. About 40 percent of diagnosed childhood asthma is attributed to exposures at home.

The burden of poor housing is not distributed evenly across populations. Families with fewer resources are more likely to live in unhealthy homes, and are less likely to be able to improve the condition of their living situations. In addition, high housing costs often put families and individuals in the position of having to trade between healthy housing and other basic necessities such as food or medication.

The forces of income segregation and racial/ethnic segregation have an enormous effect on housing suitability and health. In large metropolitan areas, the percentage of families living in “poor” or “rich” neighborhoods increased from 15 percent in 1970 to 34 percent in 2012. Moreover, disparities in housing based on racial background are substantial. Approximately 7.5 percent of non-Hispanic blacks and 2.8 percent of whites live in substandard housing. Those living in poor and dangerous housing are disproportionally people of low-income and people of color; it is not surprising then that the rate of asthma in black children is nearly two times higher than the rate of asthma in white children.

Structural forces perpetuate housing inequities. Landlords and real estate agents have contributed to racial/ethnic segregation by blocking minorities from moving to predominately white neighborhoods, which often leads to the exclusion of minorities from high-quality housing, schools, and other public services. Further, predominantly minority communities receive less investment by lenders to improve housing quality and neighborhood environments.

Increased awareness of the importance of adequate housing was a priority for the previous federal administration. The current administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) appears determined to undo all that through budgets that reduce rental assistance, cut public housing repairs, and limit code enforcements, from lead paint and mold removal to fireproofing. Health insurers and health systems are stepping in with affordable housing to help protect their populations’ health, as HUD’s interest in “safe housing” becomes increasingly and sadly delinquent.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

HOSPITALS AS AIRPORTS

As insurers cut back on hospital payments and more clinical work is done in outpatient settings, small and rural hospitals have closed. Hospital executives are pressured to develop nonclinical products and services to sell to visitors, like airports do. Commercial and retail outlets that sell food and impulse items to travelers provide 50 percent of airport revenue, yet less than 2 percent of hospital leaders are pursuing retail sales for revenue to secure financial sustainability. Beyond pharmacies, little hospital income derives from nonclinical sales. But with captive patients, visitors and employees, we might expect larger hospitals to start renting more space to retailers.

OUT OF SCHOOL, OUT OF LUCK

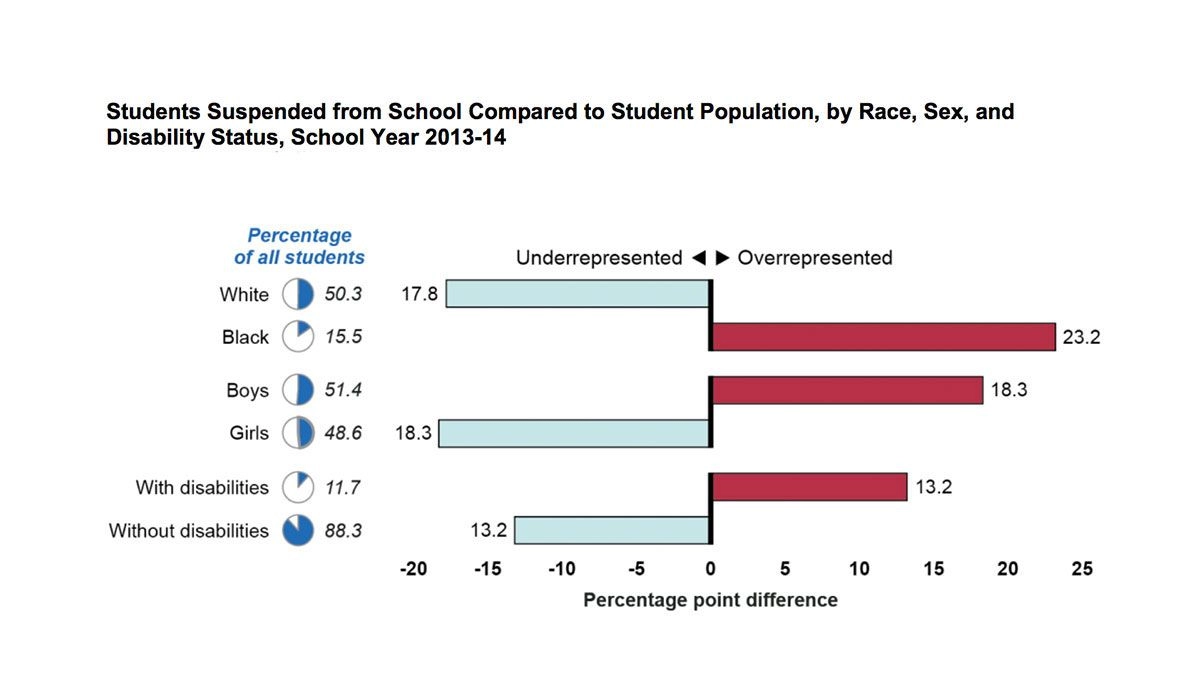

Out-of-school suspension is linked to lower grades, increased expulsions, and increased risk of incarceration. Disciplinary actions are often distributed unequally, based on gender, race, and personal ability. At the request of Congress, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) reviewed disciplinary patterns across schools. They found that Black students, boys, and students with disabilities are punished more frequently than other K-12 public school students.

As shown in the figure, although Black students account for only 15.5% of the K-12 student population, they make up 39% of the nation’s suspensions. Boys are also overrepresented in out-of-school suspensions, as are students living with a disability.

Disciplinary action through suspension is centered around a student’s behavior, which is often influenced by myriad complex social challenges such as poverty, mental illness, and lack of parental support. Most suspensions result from multiple school absences and tardy reports which are commonly linked to difficult family situations. Chronic tardiness most affects low-income students, who often care for younger siblings or work to support their family. Furthermore, teachers’ implicit biases harbored in race and gender stereotypes also contribute to the harshness of punishment delegated. Research shows that students of color suffer from harsher disciplinary outcomes from White teachers than teachers of the same race.

Suspension as a form of punishment starts as early as preschool, where boys and black students make up the majority of suspension cases. Several school officials interviewed by the GAO reported trying to move away from disciplinary actions that remove children from the classroom, which interrupt academic achievement. Between 2016-2017, seventeen states enacted legislation to restrict and reduce the number of out-of-school suspensions and expulsions.

Schools in Massachusetts are attempting to collaborate with mental health professionals and social workers to support students undergoing traumatic experiences. Districts in Texas and Massachusetts have introduced “personal break rooms” where children can calm down and redirect their emotions after a frustrating incident. Some elementary schools in Georgia report that they no longer discipline based on tardiness.—Erin Polka, PHP Fellow

Feature image from “Students Suspended from School Compared to Student Population, by Race, Sex, and Disability Status, School Year 2013-14.” United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters, K-12 Education Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities, March 2018.