Homelessness

Efforts to address homelessness have made slow progress, but we should resist mission fatigue to ensure health equity.

Read Time: 6 minutes

Published:

Homelessness

Homelessness is a brutal, demoralizing experience. Every day brings the difficult search for shelter, food, clothing, a place to wash, a place to go to the bathroom for more than 550,00 Americans. Those who find their way to shelters have three times the age-adjusted risk of dying compared to the general population. Those who go unsheltered, the so-called “rough sleepers,” have 10 times the mortality.

Homelessness has the power to move us to action like few other failings in a modern world. Unfortunately, our efforts to tackle homelessness have long fallen short. Historically, making housing contingent on sobriety and employment—forcing those who did not meet these marks to fall away and become chronically homeless—has imperiled millions. Housing First—a program that provides housing and support services without requiring employment or pretreatment for mental health conditions and substance use disorders—has gained traction. Compared to treatment first, Housing First leads to improvements in housing stability, reduced hospitalizations and use of emergency departments, and better quality of life.

Making housing more permanent and affordable is an essential first step, if dual-edged. Moving the urban homeless from their current situation offers protection, but also isolation from the little help and friendship known to these individuals, especially those with mental illness or disability. Still, rapid re-housing availability for those in need is critical.

Adding to the challenge, over eight million more Americans are one step away from homelessness. And unlike the homeless, they are often invisible. The number of renters with very low income, who use half of it for housing and receive no government assistance, has grown 25% in the past decade. Many become homeless through temporary personal or financial crises, and 40% of people experiencing homelessness are families with children. Preventing homelessness in these lower-income households requires the creation of a living wage (impossible at $7.25 an hour, the Federal figure). But prevention is also about identifying risk, and providing supportive services when an individual or family is on the brink.

About one in 10 homeless persons is a veteran, down from one in three only a decade ago. What the Department of Veterans Affairs has recognized is that homelessness is finite and its disappearance requires two ingredients: individual planning and available housing stock. Even if homelessness cannot be fully prevented, it can be responded to with immediacy, resources, and an attitude that no one should stay on the street or in a shelter for long. A community with the support of state and federal government funding—and health plans like Kaiser—that offer collaborative programming and care, can do what is needed.

Doing everything within our power to minimize homelessness is a matter of health equity. Efforts to address homelessness have made slow progress, but we should resist mission fatigue. We cannot allow the next recession, which will make matters worse for the homeless when it arrives, to add to our national disgrace.

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

DRINKING AND CRIMING

Gun owners are more likely than others to report excessive alcohol consumption. These authors studied persons who bought a new handgun and followed them for 15 years. They report that one in three of those with prior alcohol-related convictions were arrested for a violent or firearm-related crime, four times the rate of those without a driving under the influence (DUI) conviction. Younger age, male sex, and prior violence are all known risks for future violence, but DUI conviction is particularly dangerous. Only three states and the District of Columbia have enforceable statutes restricting access to legal gun purchase based on convictions for alcohol-related crimes.

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS IN PUBLIC POLICY

The United States spends far more on health than any other nation but trails many other countries in life expectancy. Despite being the richest nation in the world, we are not the happiest.

How do you measure happiness? This question motivates social scientists such as Bent Geves who contend that the answer is not merely an academic exercise but an accurate indicator of social progress. “Paying more attention to happiness should be part of our efforts to achieve both human and sustainable development,” said the former head of the United Nations Development Programme, Helen Clark.

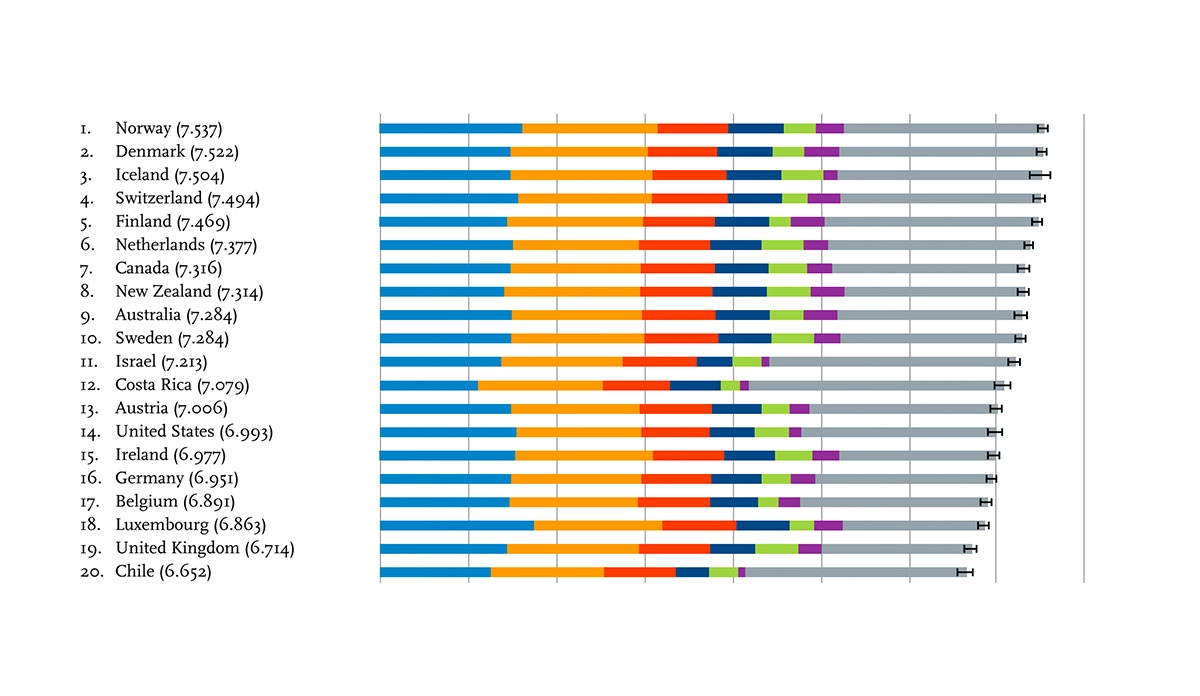

The first World Happiness Report, published in 2012, paints a sobering picture of the degree to which Americans are successfully achieving “the pursuit of happiness,” which along with “life and liberty” are among the inalienable rights enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Influenced by the UN High Level Meeting on happiness and wellbeing, the report sets out to rank levels of happiness between countries using a metric that takes a wide range of factors into account, including GDP per capita, social support, and perceptions of governmental corruption. The 2017 report “emphasizes the importance of the social foundations of happiness,” recognizing a core public health tenet that systemic factors contribute to a person’s health.

The U.S. is the 14th happiest country among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The relatively low ranking is partly explained by growing distrust in the federal government. The following graph, courtesy of Pew Research Center, highlights the low level of trust in the federal government, with the only spike occurring in the years after September 11th.

The relatively low ranking of happiness and growing distrust in government may in part explain what we are seeing worldwide with burgeoning populist movements and what we witnessed in 2016 in the U.S. when the heavily-favored establishment candidate lost to the self-described anti-establishment candidate. In an election void of tradition and marred by slander and fake news, political revolt occurred at the polls by unhappy voters.

In the report, renowned economist and Professor of Sustainable Development and Public Health at Columbia University Jeffrey Sachs writes: “The United States can and should raise happiness by addressing America’s multifaceted social crisis—rising inequality, corruption, isolation, and distrust—rather than focusing exclusively or even mainly on economic growth.”—Gilbert Benavidez

Feature Image: World Happiness Report, Figure 2.2: Ranking of Happiness 2014-2016 (Part 1), p. 20.