Health Systems and Public Health Thinking

Every health care provider—from pediatrician to geriatrician—has seen how hunger and homelessness affect health.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

Health Systems and Public Health Thinking

Every health care provider—from pediatrician to geriatrician—has seen how hunger and homelessness affect health. The disordered lives of patients disrupt appointment-keeping and medication adherence but also create problems themselves. For example, they drive depressive symptoms, high blood pressure, and hospitalizations for asthma.

Recognizing this, some health systems are paying attention. Our health system in Boston recently announced plans to subsidize housing to improve housing options for patients for whom it is accountable.

Part of a health system’s new interest in the fundamental drivers of health is financial. Medicaid, in our state and others, adjusts payments to hospitals based on whether a patient is homeless; homelessness is treated like any other complicating diagnosis, an additional cost of care. So systems can lose money if they do not collect and appropriately bill for housing status. But there are other, more charitable explanations, including the possibility that such information can drive new program development and position the health systems to help fix underlying economic and social conditions where other community services have failed, in order to improve their patients’ health.

Perhaps at core, health systems are dealing with the fundamental challenges to health in no small part because they have to: because societally we have fallen short of a collective understanding of health as a public good. Health systems may move us toward this understanding through the relevant investment in resources that can improve the health of their patients.

In many ways, the embrace by health systems of the fundamental drivers of health is welcome. Health systems are ubiquitous; the machinery of medicine touches all our lives and its administrators are in a position to have real influence if they choose to change how they do what they do. But, should health systems own and run food pantries, or manage apartment buildings? Should medical systems, often central to a community’s economy, take on the provision of social services as part of patient care? Should health systems assess what they cannot reliably address? And if they do, will these new services drag resources from diagnosis and treatment, the centerpieces of medical care?

Health systems are powerful political entities as well. They can convene stakeholders, influence state and local policymakers, spur government action to address housing and education and hunger with an eye toward health improvement. Can health systems’ new engagement with the foundational drivers of health spur a long-overdue national reckoning and a re-commitment to improving the conditions that can actually make Americans healthier?

Warmly,

Michael Stein & Sandro Galea

UNCOMMON LAW

Courts for chronic offenders with psychiatric disabilities, so-called mental health courts (MHC), have now been around for twenty years. MHC judges are expected to practice law as a healing profession, and not just as common law arbiters, to divert individuals from the criminal justice system to community-based treatment. Most new judges who preside over the 300+ courts in the US still have little training or experience implementing the legal and clinical procedures at their disposal for such problem-solving justice. This qualitative study offers portraits of four such “alternative” courtrooms and analyzes judges’ patterned responses to allegations of client misconduct.

PrEP-PING FOR NEW PROBLEMS

The recent availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has decreased the risk of HIV infection after sex without condoms. With lessened worries about acquiring HIV, HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM), the primary users of PrEP, might have more unprotected sex and increase their risk of other sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia that are already common among MSM. A study from Boston confirms this worry. Men who used PrEP were more than twice as likely to have one of these other infections than MSM who were not using PrEP. Willingness to engage in condomless sex has wide public health implications for MSM even when the risk of HIV is reduced with PrEP.

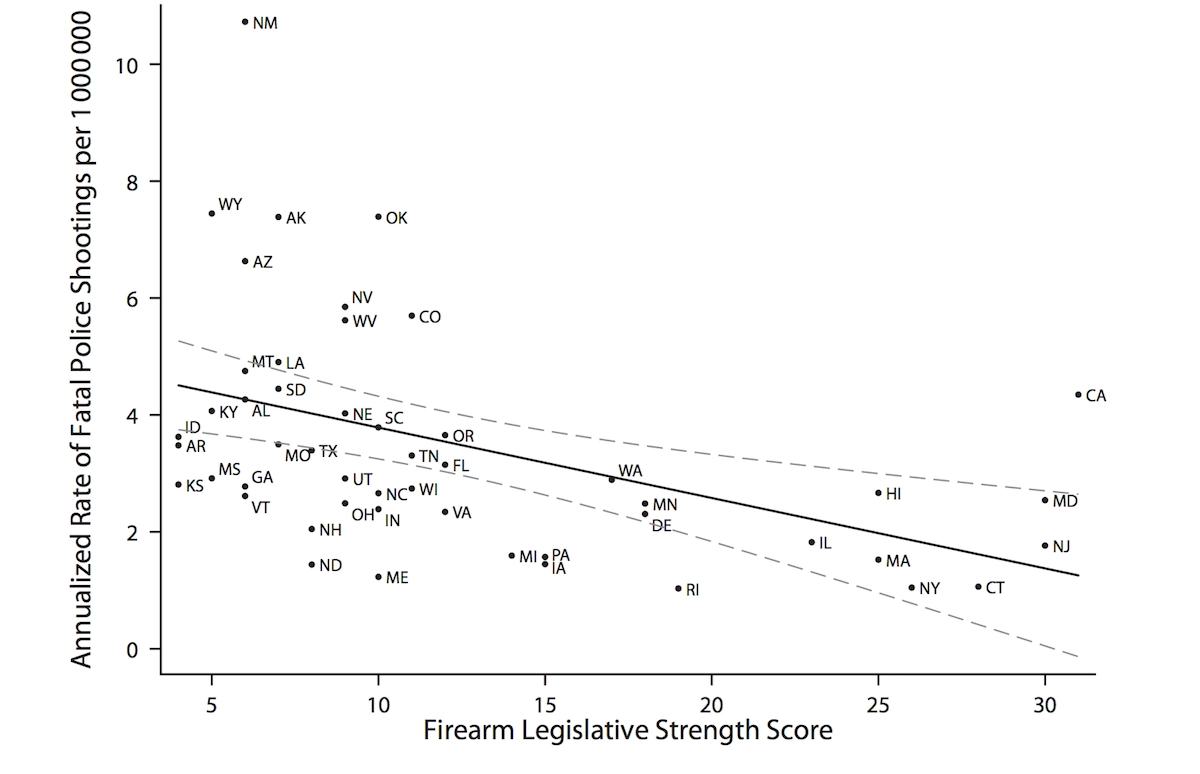

GUN LAWS REDUCE FATAL SHOOTINGS BY POLICE

States with stricter firearm legislation have fewer fatal police shootings—defined as the rate of people killed by law enforcement agencies—according to research in the American Journal of Public Health.

The authors used two sources of data to show this relationship. First, the Brady Center’s legislative scorecard for firearm laws was used to determine the strength of state-level legislation. The scorecard highlights seven categories of laws, such as background checks, duty to retreat, and banning guns from public places. The higher the score, the stronger the firearm legislation is within that state.

Second, The Counted, an online database by The Guardian, was used to assess the number of fatal police shootings. A total of 2,021 fatal police encounters occurred in the United States between January 2015 and October 2016. Firearms were responsible for 1,835 of these deaths.

The analysis showed that even after controlling for age, education, violent crime rates, and household gun ownership, states with the strongest firearm legislation had a 51% lower incidence of fatal police shootings compared to states with the weakest firearm laws.

Laws that strengthen background checks, promote child and consumer safety, and reduce gun trafficking are linked to lower rates of fatal police shootings.

Graphic: Aaron J. Kivisto, Bradley Ray, Peter L. Phalen, “Firearm Legislation and Fatal Police Shootings in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 7 (July 1, 2017): pp. 1068-1075.

DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303770