Guiding Principles for Writing About Immigrants and Immigrant Health

Shifting our strategies and terminology used for communicating about immigrants and immigrant health is necessary for building trust and mitigating stigma.

Read Time: 5 minutes

Published:

The language we use shapes how we treat people. With our words we can acknowledge someone’s humanity or diminish them to a stereotype. How we talk about people also reveals our deeply held explicit and implicit beliefs and perceptions. Recognizing this, our team created a guide for researchers and clinicians on the use of language that respects the dignity and humanity of immigrants.

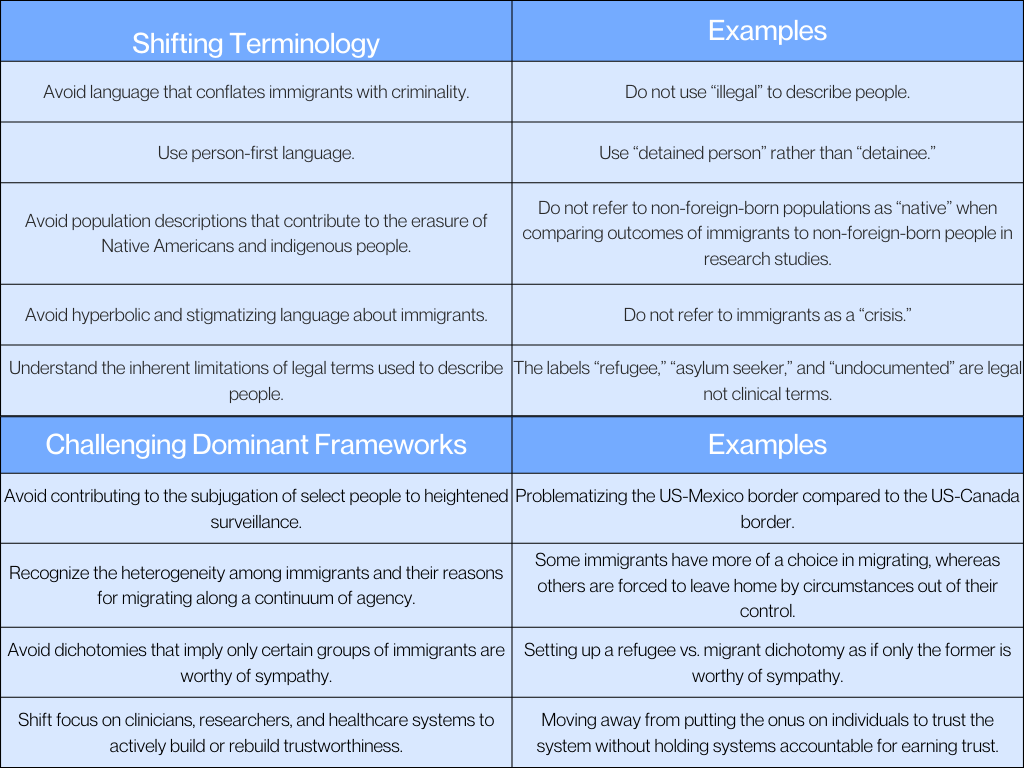

Our guide adds to the American Medical Association health equity guide by delving more deeply into language pertaining to immigrants—a large, growing, and diverse group often subjected to individual and structural dehumanization, criminalization, stigma, and discrimination in today’s political climate. Our recommendations focus on shifting terminology and challenging dominant frameworks in order to better serve immigrants.

In terms of shifting terminology, we identify how our language can dehumanize immigrants and define their worthiness. And we make recommendations about inclusive language choices. For example, when we use terms like “illegal” to describe immigrants without documentation, we reduce whole individuals to their immigration status while also criminalizing their existence. Further, because of U.S. media portrayal and political rhetoric, terms like “illegal” can conjure up images of Brown people crossing the U.S.’s southern border. Yet the reality is that most immigrants without documentation enter the U.S. through legally sanctioned pathways. To avoid reducing people to stereotypes, we suggest using “undocumented” rather than “illegal” and person-first language, such as “person seeking asylum” instead of “asylum-seeker.”

Additionally, we call for shifting away from using the language of White “native” populations when comparing immigrants to non-foreign-born populations in research studies. By referring to our non-foreign-born populations as “native,” we contribute to the erasure of Native Americans living in the Americas before the formal creation of the United States who endured genocide. We argue that our current language should both accurately portray history and the current existence of Indigenous people. Further, studying immigrants in relation to White “natives” misses how immigrants and Native Americans have intersecting experiences of marginalization, state regulation, and surveillance, such as U.S. policies of family separation that have affected Native Americans and immigrants alike.

As language shifts, so will our strategies, maintaining our commitment to equity as clinicians and researchers through ongoing reflection and iteration.

Shifting our terminology requires us to challenge the dominant underlying frameworks that lead us to use such language. For example, even the label “immigrant” or “immigrant health” belies an important reality: immigrants are a heterogeneous group of people who have come to the U.S. for many reasons via multiple pathways. While some immigrants are forcibly displaced from their home countries, other immigrants have more agency in whether to leave their home countries based on their wealth, resources, and countries’ conditions. This variation highlights how each immigrant faces distinct needs and challenges post-immigration. Homogenous categories hinder our ability to meet the needs of each immigrant.

Acknowledging that immigration doesn’t happen in a vacuum also requires us to acknowledge that countries like the U.S. and United Kingdom (among others) played a role in destabilizing numerous countries and territories, forcing their people to migrate. In this way, labeling current migration challenges as a “refugee crisis” or “migrant crisis” puts the focus on people rather than the harmful policies and practices that necessitate their flight. This hyperbolic language stigmatizes them over holding accountable countries and state actors who engage in war, violence, torture, corruption, and other human rights violations that contribute to people fleeing or leaving their countries. A similar stigmatization can occur when we focus on certain borders (i.e., the U.S.-Mexico Border) over others (i.e., the U.S.-Canada Border). This geographic bias subjects some immigrants should be under heightened surveillance and not others.

Finally, we call for shifting our language around trust. Instead of using language that implies marginalized communities are at fault for mistrusting health care providers and systems, we must recognize that mistrust from various groups—including immigrants—is justified. Our medical systems has a history of exploiting marginalized communities, and some ongoing practices perpetuate mistrust. As just one example, earlier during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health officials in at least 35 states were sharing addresses of those who tested positive for the coronavirus with law enforcement agencies. In at least 10 of those states, the health agencies were also sharing names. Therefore, the onus is on health care institutions and practitioners (as well as those in other sectors) to earn trust and become trustworthy, rather than simply expecting immigrants and other marginalized groups to trust them as a default stance.

Building trust hinges on listening to and valuing individual voices, which is why the recommendations outlined in the table below are a starting point, not a conclusion. As language shifts, so will our strategies, maintaining our commitment to equity as clinicians and researchers through ongoing reflection and iteration.

Photo via Getty Images