Emergency Unpreparedness

The United States tends to fund and focus on emergencies after they happen and once they have already become disastrous. State and local emergency preparedness funds and hospital preparedness funds have dwindled by one-third and one-half, respectively, since 2004.

Read Time: 3 minutes

Published:

If the United States’ federal discretionary budget is an indicator of its priorities, at $611 billion and rising, military defense is king. What does that say, then, about our commitment to a different kind of defense—the kind that protects residents from biological threats?

State and local emergency preparedness funds and hospital preparedness funds have dwindled by one-third and one-half, respectively, since 2004. On the other hand, the FY2018 federal budget under the Trump administration establishes an Emergency Response Fund of an unspecified amount. This could be a victory for the public health officials who have been advocating for such a fund since the Ebola and Zika outbreaks of recent years. However, the Department of Health and Human Services, which would ostensibly be responsible for allocating money to the fund, will face drastic cuts in the new budget. This makes it unlikely that a sufficient amount will actually be put into this fund.

How much would an adequate Emergency Fund cost? To start, the Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) estimates that the flu costs about $94 billion each year. Antibiotic-resistant infections carry a $55 billion price tag. Infectious diseases cost the U.S. around $120 billion annually. For the past 30 years, about one new contagious disease has emerged annually.

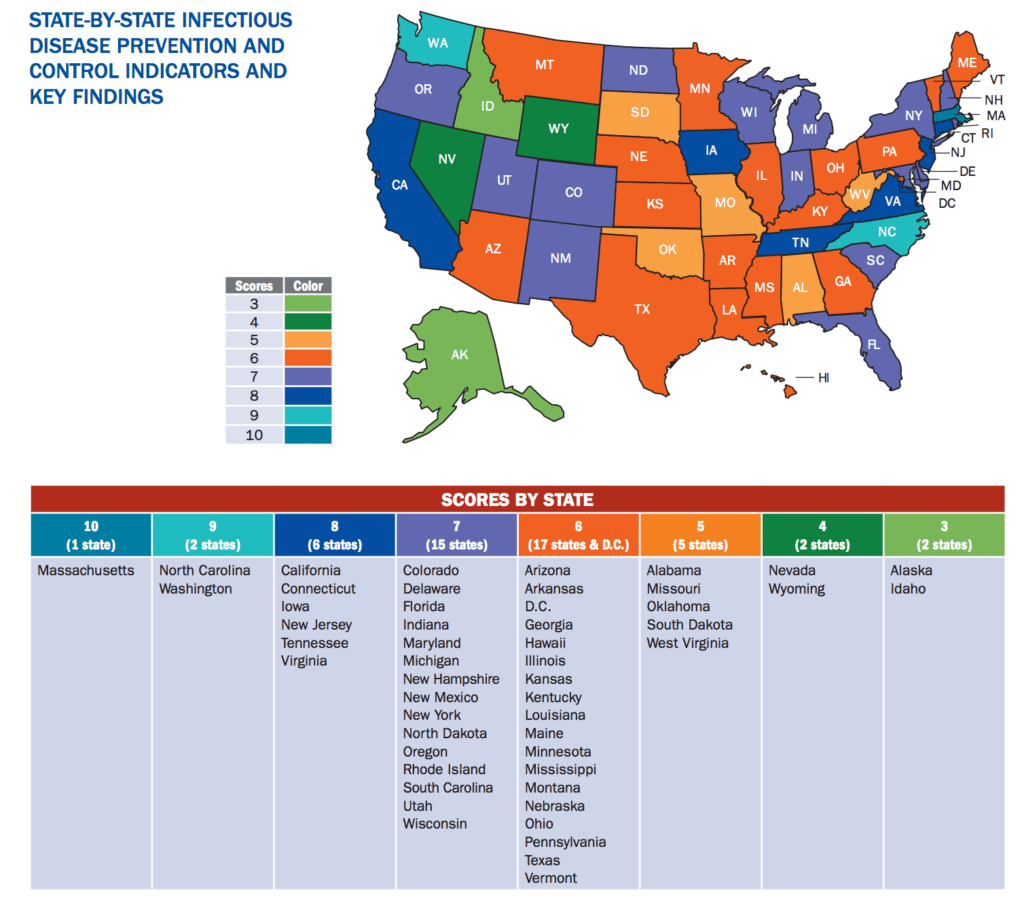

These cost estimates have been detailed in a report from TFAH called Ready or Not: Protecting the Public from Diseases, Disasters and Bioterrorism, published annually from 2003-2012, and most recently again in December 2016. The first half of the report describes ten indicators of emergency health preparedness by state. Indicators include funding, vaccination rates, climate change readiness, and biosafety training. The second half provides recommendations to address gaps in areas like vaccination, infrastructure, leadership, and the public health workforce.

As shown in the above graphic, only one state—Massachusetts—achieves all indicators of readiness. The majority of states fall in in the 6 to 7 indicator range. Alaska, Idaho, Nevada, and Wyoming have met 3 or 4. The TFAH argues that basic preparedness should be a goal regardless of variations in each state with regard to available resources, political climate, and their distinctive community health priorities.

“The current system is not built for ‘readiness’,” the report says. The United States tends to fund and focus on emergencies after they happen and once they have already become disastrous. When the worst transpires, the systems designed to respond—hospitals, police, public health officials, and other trained specialists—are too often uncoordinated and thus inefficient.

By shifting to a more forward-thinking perspective, health emergencies and natural disasters will cost less money, and more importantly, result in fewer unnecessary deaths.

Feature image: clement127, Biohazard, used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

State-by-state graphic from Trust for America’s Health Ready or Not….